Long before “fake news” wedged itself into American vernacular, “fake” or “engineered” news on film had a powerful influence on democracy and world regimes. A few years ago, one of my history students observed that a film reel of Teddy Roosevelt from the 1915 Panama–California Exposition was shockingly authentic. After viewing the reel, my student reflected on how useful it was to see the world “exactly” as it was lived in history. This response gave me pause. Had I done enough to introduce the reel and complicate it as a primary source? My student accepted the moving images on the screen as pure historical truth. This reflection helped me realize I was missing an opportunity to use newsreels as a teaching tool to engage critical analysis and media literacy in my history classroom.

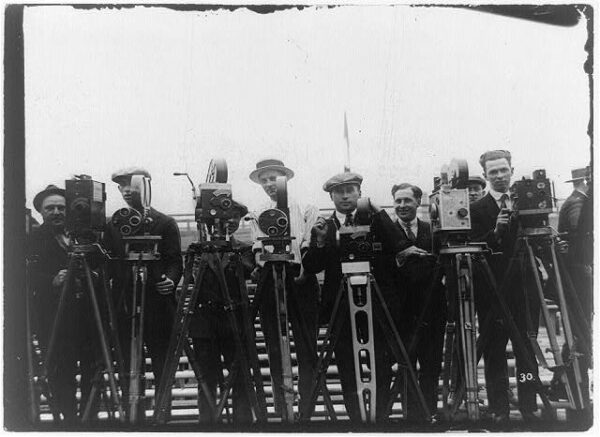

Emerging media companies marketed newsreel cameramen, like these cameramen in 1921 New Jersey, as heroic, daring men of the world. Library of Congress, public domain

A uniquely 20th-century format, newsreels were first called actualities because of their perceived “actual” delivery of living images. The word newsreel eventually emerged as a compound collaboration of two distinct industries, entertainment and journalism. Newsreels focused on current events, catastrophes, sports, and fashion shows. Viewed today, these films seem quaint—sometimes silent, often black and white, flickering across our screens—and are valued as primary sources. When such visual sources are packaged as “news,” it is all too easy to forget that they are the product of individual choices in service to an agenda. In an era that finds students and teachers using technology such as TikTok, newsreels can be an excellent tool to discuss the creation of a source and the manipulation of images and information. In this way, newsreels can help instruct students in the critical analysis of new media.

Perhaps no other American is more closely associated with the introduction of life on film than Thomas Alva Edison. In many ways, Edison exemplified the transformation in American culture that typified his era at the turn of the last century. In 1889, Edison invented the Kinetoscope, a device used by individuals to “peep” into real-life pictures in motion. Edison made early reels for these small kiosks or “peep shows,” eventually producing pictures in motion for a collective theater audience. One of his early theatrical reels offers a lesson in the production and motivation for shaping the news. In 1901, Edison presented a newsreel on the execution of Leon Czolgosz, President William McKinley’s assassin. As the inventor of the modern electric lightbulb and electric power generator, Edison used this depiction of an electric chair execution to promote his inventions. Edison presented the film as realistic footage, combining establishing views of the actual prison where Czolgosz was electrocuted with a staged reenactment. This film is today cataloged at the Library of Congress under the title, “Execution of Czolgosz, with Panorama of Auburn Prison.” A close reading of the catalog listing confirms the reenactment, but my students might easily consume the film as an actual historical moment.

When visual sources are packaged as “news,” it is all too easy to forget that they are the product of individual choices in service to an agenda.

In one shot from the four-minute film, officials look at an electric chair that has a separate apparatus of four lightbulbs, presumably made by Edison, attached to it. One official flips the switch to indicate, for the camera, the active electric current. When I use this film in class, I ask my students if this use of light bulbs created prestige for Edison and his inventions. My students recognize that Edison’s business interests are uniquely represented in this staged reel.

Newsreels can also introduce conversations of race and gender in the early 20th century. In my women’s history class, I show newsreel footage from the March 1913 women’s suffrage parade in Washington, DC. Unlike the Edison reel, this footage is not a reenactment, but it illustrates questions of representation. I start the reel with guiding questions: Who is not represented in the film? Do you see women of color? Do you see any men and if so, how are they presented? After we discuss what is visible in the film, I offer basic information about the white, male cameramen creating similar newsreel sources.

Using newsreels in the classroom can help engage students in a . . . dialogue about the responsible interpretation of new and old media technology.

In the early 20th century, emerging media companies marketed newsreel cameramen to the public as heroic, daring men of the world. Almost exclusively white men, these newsreel cameramen recorded headlines while becoming the headlines themselves. In 1915, William Randolph Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner touted one such cameraman, Arial H. Varges, as having “Characteristic American Resource and Bluff.” Varges “Makes His Way Into Places Where No One Else Can Get Admission and Brings Back Results Worth While.” I ask my students if these newspaper headlines add authenticity to the reels themselves. Does this new contextualization confirm or refute their original impressions of the reel? Students generally become more skeptical with the visual newsreel once they consider potential manipulation involved in the film’s creation and presentation. These cameramen presented reels as “authentic news” from their individual perspectives and in service to major companies with social and economic agendas. In our conversations about the creation of newsreels, I watch students connect their higher-level analysis to more modern technology. A society getting used to new motion picture technology in the early 1900s mirrors our own dilemmas with truth and authenticity in new media technologies. By contextualizing the creation of past newsreels, we can better evaluate contemporary media bias.

Evaluating primary sources is an important part of the historian’s work and a critical component of 21st-century education. History is uniquely positioned to help students learn how to interrogate information and question visual media by analyzing perspective, to say nothing of visually manipulated images in new media. Newsreels not only invite us into historical events but also help us teach students about the personal, economic, and political motivations in creating the sources themselves. It is incumbent upon history educators to remind students that someone wrote that journal, snapped that photo, or cranked that camera. Using newsreels in the classroom can help engage students in a historical moment and open a dialogue about the responsible interpretation of new and old media technology.

Julianne Johnson is an associate professor of history and faculty co-coordinator of the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at College of the Canyons. She tweets @professorjuliej.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.