Although we have always cared about and supported teaching as a department, the changes required by the COVID-19 pandemic meant that, in the last year, we came together as teachers more than ever before. Our learning curve has been steep, but we have become better, more reflective, and more collaborative teachers because of our collective efforts to rise to the challenges of the pandemic.

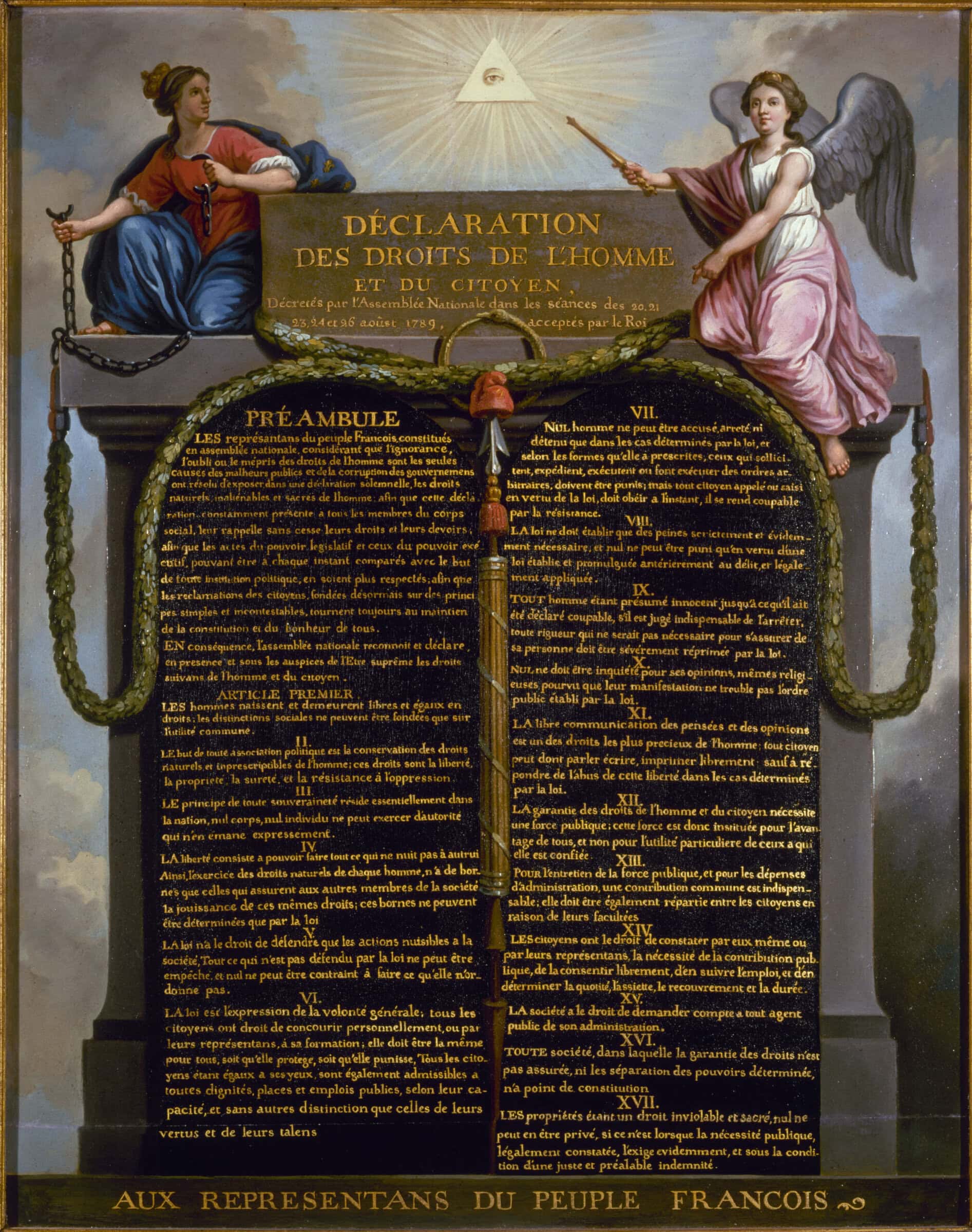

Both students and instructors reported that they appreciate the Zoom chat as a pedagogical tool and enjoy having guest speakers pop in from around the world. Lucas Law/Unsplash

Prior to COVID, our department offered a handful of online courses, all developed with the help of a university team. When our campus went completely remote in March 2020, we went into triage mode, hastily scheduling training sessions on using Zoom and recording our own lectures. To help with the sudden switch to remote instruction, we also gathered and shared best-practice information, expanding our conversations to encompass larger pedagogical issues. Taking a campus-wide online teaching academy as both a starting point and inspiration, we offered departmental workshops on methods, approaches, and tools over the summer.

Hoping to learn from our pedagogical experiments as they unfolded, our undergraduate studies committee (USC), made up of students, faculty, and our undergraduate advisor, conducted a self-study over the course of the fall 2020 semester. Their goal was to assess our emergency practices to advance learning and teaching in the short and long terms. Members of the USC shared firsthand experiences, surveyed students and instructors, initiated teaching conversations in faculty meetings, and hosted a mental health workshop and end-of-semester town hall.

The USC’s work confirmed some of our hunches about pandemic teaching conditions. Our students have a marked preference for synchronous courses, especially at the upper level. They prefer cameras to be on. They dislike having to navigate a wide array of learning platforms, some organized better than others. Our remote students are keen to return to the classroom when health conditions improve, while our in-person students are grateful for face-to-face instruction.

The undergraduate studies committee’s work confirmed some of our hunches about pandemic teaching conditions.

The USC’s research also revealed insights that are more generally useful as we return to in-person instruction. The widespread shift to more low-stakes assignments instead of proctored exams and written work instead of in-person discussions has increased student workloads. Students reported greater difficulties keeping on top of multiple deadlines for these written assignments. Instructors also reported feeling overwhelmed by the additional grading. From this, we learned that we needed to cut some of the extra work we had assigned upon going remote, provide more reminders and clearer instructions, adopt time-saving methods (such as course help discussion boards), stick to regular deadlines for recurring assignments, provide more midterm feedback, and reach out to at-risk students individually. Adapting to a new instructional format made us go back to the basics, to learn (and relearn) lessons familiar to expert teachers as new modes of instruction created and magnified problems. The sense of feeling like novices in our suddenly all-remote world made even long-time instructors keen to consider the student view and to be more intentional in course design and lesson plans.

Given what we’ve learned from the USC study, and our experiences as instructors and administrators, we are anticipating some lasting changes to our teaching. Perhaps most importantly, we will need to move beyond the remote versus in-person teaching binary. Having asynchronous learning materials in our toolkits can enable us to free up in-class time for more interactive forms of learning. Both students and instructors appreciate the Zoom chat as a pedagogical tool and enjoy having guest speakers pop in from around the world. Many of our instructors have made massive investments in purposefully asynchronous courses. Some students—especially those seeking general education credit—have reported a preference for such courses. As long-time online instructors well know, these courses offer scheduling and geographic flexibility and self-pacing. One of the challenges we face moving forward is figuring out how to match future online offerings with student demand; another is our ongoing capacity to meet new expectations for instructional services, such as posted versions of in-person lectures.

Our venture into remote teaching also revealed opportunities for accessibility and inclusion. Some remote teaching technologies have improved accessibility, such as closed captions on recorded lectures, which can aid understanding for all students. We know, too, that some students found it easier to participate in a Zoom room than a class that meets in-person.

We will need to move beyond the remote versus in-person teaching binary.

Having been liberated from our expectation of a midterm and final in large lecture classes, we are likely to continue to experiment with essays, projects, and other creative work, including more work with digital components such as annotated playlists and infographics.

By exacerbating the college student mental health crisis and economic precarity, the pandemic has intensified and accelerated our efforts to develop a more empathetic and supportive departmental culture. We now embrace compassion and flexibility as core pedagogical tenets; favor less stringent syllabus text on absences, excuses, and extensions; encourage syllabus text on campus and community services and resources; and look more closely at the price tags and e-reserve availability of assigned books.

There is plenty we still don’t know, which may take years to figure out. What does a credit hour mean if a lecture that once took 50 minutes can be delivered in recorded format in a fraction of that time, with the interactive activities taking new forms? Anecdotal evidence suggests that students are learning as much as in other years—indeed, some instructors report even higher engagement and performance—but the specific skills learned appear to be slightly different, as, for example, assessment has shifted from exams to papers and group projects. And while it is heartening to see some students excel and engage with the material and their classmates in innovative ways, an alarming number of students (data indicates that they are disproportionately first-generation students) have struggled this past semester.

The difficult circumstances of the pandemic have pushed many of us—faculty, graduate students, and undergraduates—to our limits. Yet even as our work days have stretched long into the night, members of our department have participated in pedagogical discussions with remarkable enthusiasm and interest. Many of us have been eager to talk more about teaching; it just took a global pandemic to force us to carve out the time to do so. It has been rewarding to describe experiences, exchange ideas, and wrestle with common problems. Many of us are rightfully proud of our efforts, and it brings us joy to share what we have learned.

The greatest lesson we learned during the pandemic is the need to continue to center pedagogy in our collective life and to make our emergency practice a core part of the ongoing culture of our department.

Stefan Djordjevic is the undergraduate advisor, Kristin Hoganson is the Stanley S. Stroup Professor of United States History and director of undergraduate studies, and Dana Rabin is professor and chair of the Department of History at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.