As institutions transition to online instruction in the face of COVID-19, historians are struggling with what it means to teach history online. The AHA had planned to announce guidelines in June 2020 for online teaching in history, and we will continue to work to do so. In the meantime, we are publishing a series of short pieces in Perspectives Daily to help the many historians now working to navigate this emergency.

We offer these pieces with a few caveats. Much of what can be done quickly is not properly online instruction(courses envisioned for online or hybrid execution). Rather, for many, this is a rapid transition to remote instruction. Similarly, much of the advice depends on your own institutional circumstances; with regard to policy, particularly ADA policy, always defer to the rules of your home institution. Still, we hope these posts will help support student learning during these turbulent times, and we invite discussion of them and an exchange of ideas—both broadly conceived and narrowly practical—on the AHA Members’ Forum.

As a newly minted PhD in 2017, having never taught an online course, I joined the history faculty of the Minerva Schools at KGI. During their four years of study, each Minerva student cohort lives together in different locations around the world. All courses are taught online using the educational platform Minerva Forum, which enables synchronous teaching based entirely on active learning principles. My first year at Minerva dispelled any concerns about teaching remotely and opened my eyes to the possibilities of online learning platforms. With the rapid closure of college campuses in response to COVID-19, historians around the world are now preparing to embark on a similar journey.

Lean Forward/Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0

Faculty and instructional technologists have already begun sharing tools and guidelines for moving courses online (Daniel Stanford’s compendium of institutional resources is a particularly helpful reference). Many institutions have instructional technology or learning design teams that can direct faculty to specific resources. The quick transition from traditional classrooms will be challenging, but tools are available to ease the change.

Many institutions are offering their faculty access to the video conferencing platform Zoom, which enables many of the interactions essential to effective virtual learning. One of the best ways I’ve found to encourage engagement in online classes is through breakout groups, in which small groups of students work together to analyze primary sources, collaboratively respond to a question, or assess the argument and evidence presented in a secondary source. When we reconvene as a class, each group presents its findings and offers constructive feedback to the other groups.

There are two keys to this kind of activity. First, it’s essential to provide clear instructions and expectations for what each breakout group should produce or be ready to present to the full class. Second, after the full class reconvenes, students need precise instructions for what to do while other groups present. If one breakout group is presenting its analysis of a primary source, for example, I might ask the rest of the class to listen carefully and be prepared to explain similarities and differences with their own source.

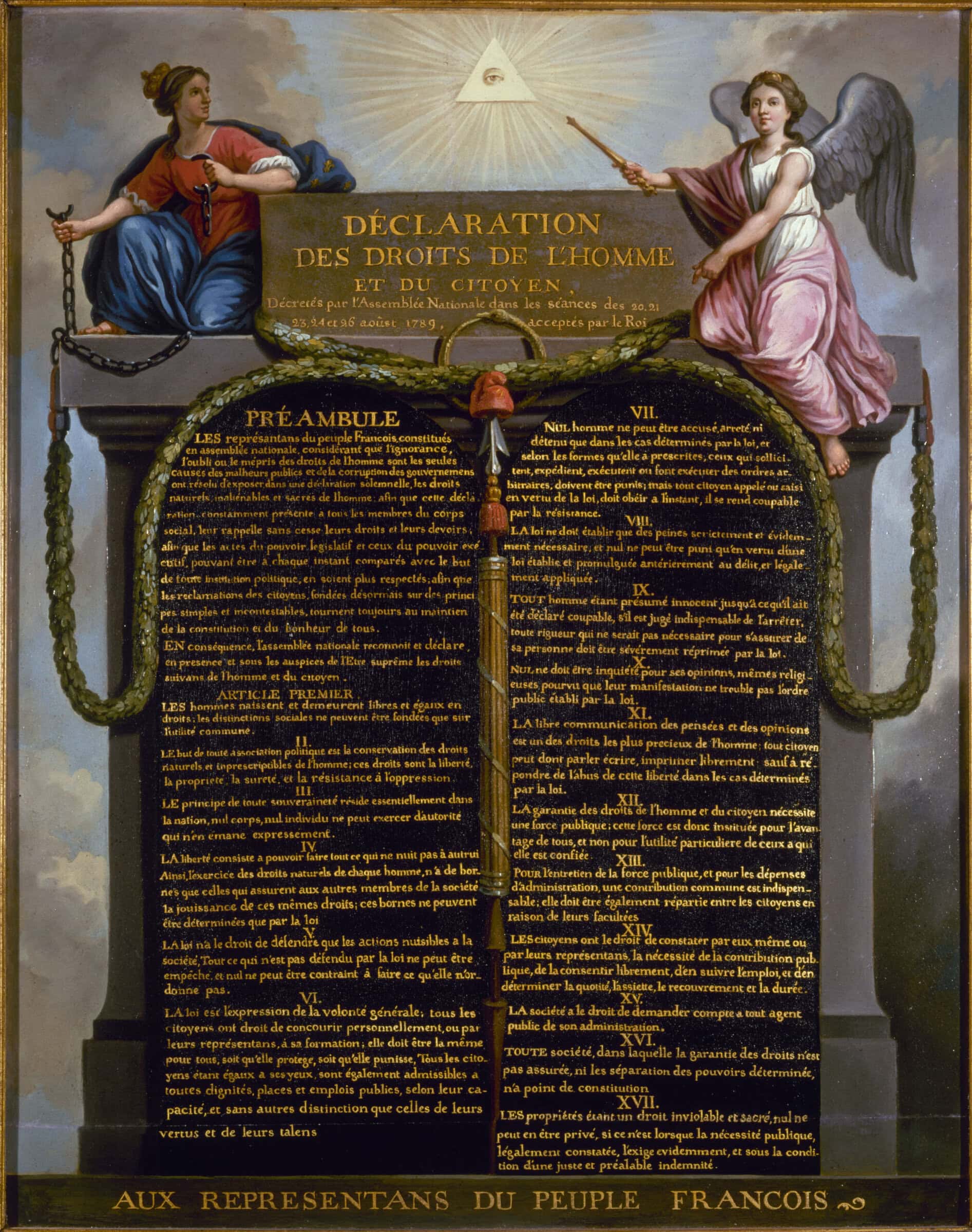

Polls are also possible within Zoom. As historians, we know that most questions worth pursuing cannot be answered with a simple “yes” or “no.” Still, yes/no or multiple choice polls can be used to conduct a quick comprehension check, to prompt discussion, and to ensure that everyone thinks through a given topic and has an opportunity to share their thoughts. For example, in a class session on Atlantic revolutions, we ask students: Which revolution was the most “radical”? Their options are the US, France, Haiti, and Mexico. This question obviously does not have a single right answer, and typically it leads to a deeper discussion about the significance of intellectual vs. socio-political change. In a class session on World War I, we use a poll to prompt students to consider whether the world before and after World War I is best characterized by continuity or rupture in terms of a given theme—for instance, human rights.

While small breakout groups and critical thinking exercises can be transferred easily from in-person to online classrooms, traditional lectures cannot. Even the most scintillating lecture is likely to prompt students to head over to another browser tab if it runs longer 15 minutes. At Minerva, faculty talk for only a few minutes at a time, usually to bring different threads of a discussion together or to clarify key points. This teaching style may not work for every professor, but every class can benefit from “engagement tasks.” Faculty and students can share their screens through Zoom and analyze primary sources directly on their screen. Faculty can also experiment with prompting students to pose or respond to questions in the Zoom chat box in order to “warm up” for broader participation in the class at large (with frequent reminders to keep things civil). Meanwhile, lengthier lectures are best assigned as videos or podcasts for pre-class preparation.

Inserting verbal signposts along the way can give classes direction and emphasis. I might begin by telling students: “throughout today’s class, I want you to focus on the significance of gender in narratives of World War II.” Then, I’ll make sure to come back to that topic with a poll later in the class or a breakout activity that prompts students to think about how gendered assumptions informed a particular primary source. Each class ends by circling back to the topic or skill that was highlighted at the beginning. In this case, I might ask, “What was your key takeaway about the significance of gender in narratives of World War II?” and call on several students to respond. Ending this way not only provides a sense of closure to the session, but also gives me an opportunity to gauge what students found valuable about the class and reinforces the sense that, yes, learning happened here.

These approaches to teaching and learning may be new to faculty and students both; one of the most important things that we (as faculty) can do in the months ahead is to openly address the challenges that we are all facing and to explain clearly the format of each new class. For instance: “I know lectures are difficult to follow online. So I’ll begin by charting the development of X phenomenon for 15 minutes. Then we’ll do a quick poll to give you all a chance to evaluate X and let me know if you have any questions. Then I’ll break you up into small groups to talk through Y question together. Throughout, make sure to pay attention to Z.”

Effectively using platforms like Zoom requires not only that students and faculty quickly get up to speed on a new system, but that everyone have access to strong internet connections. As historians, we know how significantly context—personal, cultural, geographical—shapes historical experience. It can be easy to forget that our students, too, are shaped by history. But when some students don’t have a quiet space in which to take a class at home, or the resources for a strong internet connection, this context can have a profound impact on their performance. Faculty must keep such disparities in mind, and perhaps even invite discussion of them.

My hope for the long term is that moving massive numbers of courses online will prompt greater discussion of best practices in digital pedagogy. In the short term, we can help each other by sharing ideas for activities and approaches to turn the forced migration of courses online into an opportunity and make the best use of available resources.

Sonja G. Ostrow is an assistant professor of arts and humanities at the Minerva Schools at KGI, where she teaches courses in history and communications. She can be reached at sostrow@minerva.kgi.edu.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.