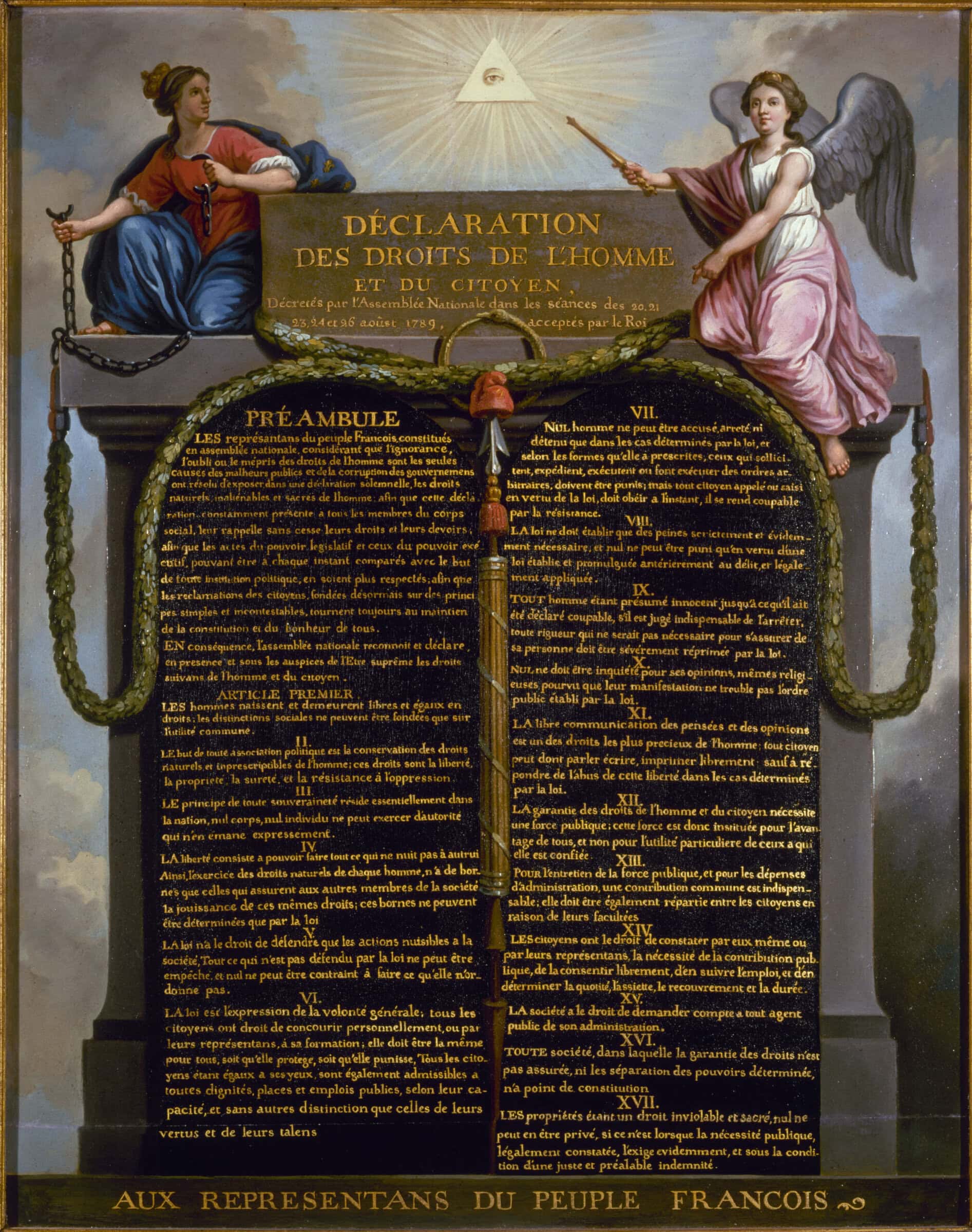

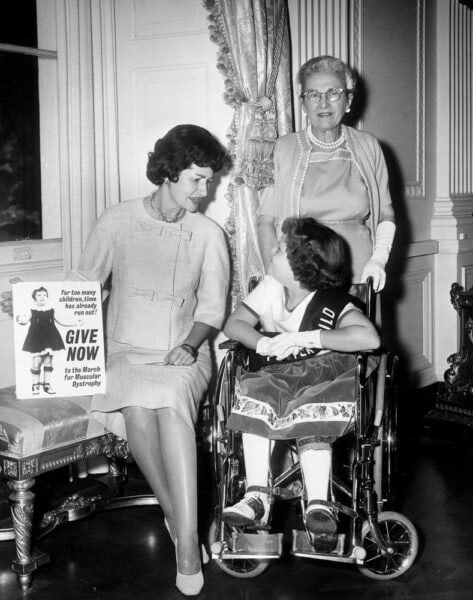

A few months ago, Celeste Sharpe, then a graduate student at George Mason University (GMU), defended what is purportedly the first born-digital dissertation in the discipline of history. Sharpe describes her project, They Need You! Disability, Visual Culture, and the Poster Child, 1945–1980, as an examination of “the history of the national poster child—an official representative for both a disease and an organization—in post–World War II America.” In her project, Sharpe argues that “poster child imagery is vital for understanding the cultural pervasiveness of the idea of disability as diagnosis and how that understanding marginalized political avenues and policies outside of disease eradication in 20th-century America.” AHA Today caught up with Sharpe recently about the process of creating a born-digital dissertation, advice for graduate students considering similar projects, and future prospects.

As a graduate student at George Mason University, Celeste Sharpe produced what is purportedly the first born-digital dissertation in the discipline of history.

Why was digital the best format for this project?

CS: My approach to this project and my rationale for pursuing a fully digital dissertation are grounded in the fields framing this project, particularly visual culture studies and disability studies. What my work reveals are the complex and shifting negotiations made by the poster children themselves, their parents, and the people working in health charities to create and circulate this imagery in post–World War II America. Since disabled children have been historically silent and silenced in the archives, I thought it vital that this project foreground their experiences.

The visual sources are central to this study and a digital presentation allows readers to see the images I discuss in the course of my analysis and, more importantly to my mind, opens the imagery to broader investigation by the viewers themselves. In addition, the March of Dimes and Muscular Dystrophy Association have not digitized their holdings and both charities have laid off their archivists. Given the tenuous state of both organizational archives, the digital project makes a valuable contribution in gathering, analyzing, and presenting these increasingly unreachable items.

I chose to use Scalar, a digital publishing platform out of the University of Southern California. Building out this project in Scalar allowed me to interrogate and remix the elements of a history dissertation. The platform enabled me to achieve my two main goals: make a project with multiple access points into the content AND create a structure that reveals and reinforces the complex connections between people, charitable organizations, ideologies, and politics.

At what point of your research/writing process did you realize that digital would be the best way to present your work? What did you do next? Did you face any resistance?

CS: I came into the doctoral program with a strong dissatisfaction with the rigidity of the print-oriented format of a thesis/dissertation with regards to the relationship between media and text. I’d done my master’s thesis on antebellum southern photography and experienced a lot of frustration with the style requirements for images, which structurally made it difficult to treat the images as more than illustrative. So early on, I was interested in pushing the form of a dissertation even though I didn’t have a set idea what that would look like. When I settled on my research topic, I immediately spoke with my advisor Dr. Suzanne Smith and my committee members Dr. Ellen Wiley Todd and Dr. Stephen Robertson about it being an entirely digital project. They were all on board from the start; both the objects of study and the kinds of questions I wanted to pursue just made sense as a digital project, which allowed me invaluable space to experiment and conceptualize my project.

Lady Bird Johnson meets with Lola Lucas, national poster child for the Muscular Dystrophy Association of America (MDAA), and her grandmother, James T. Malin, in the White House. The poster to the left reads “for too many children, time has already run out! GIVE NOW to the March for Muscular Dystrophy.” Credit: Abbie Rowe/White House Photographs/ John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

How helpful were the AHA’s guidelines on dissertations and digital scholarship in helping you through this process?

CS: The Guidelines for Digital Dissertations created by the GMU history department’s Graduate Studies Committee (huge shoutout to Sharon Leon!) were particularly helpful as I pursued this project. These guidelines reference the AHA’s Statement on Standards of Professional Conduct. Conversations around GMU’s digital dissertation guidelines began in 2014, with the final version approved in 2015, which aligned with my time on dissertation (January 2014–November 2016).

Did you come into the process with any skills in digital humanities? Did you face any obstacles along the way in terms of technology?

CS: I entered the doctoral program with no digital humanities skills to speak of! The GMU PhD program has a two-course sequence in digital humanities theory and praxis, but there’s only so much that can be covered in one semester of learning technical skills. My main obstacle was trying to find resources to do the kind of digital work I wanted to do.

Originally, I’d wanted to do computer vision analysis on the corpora of images, but had to let that go as one challenge too many for this project. And this was a decision I made because of how the conversations developed around copyright and image permissions, and what was needed to archive or deposit with the library. The two charities I studied are quite risk-averse, and so they’ve adopted a commercial and litigious approach to their archival materials: charge for almost every use, assert copyright aggressively, and back it up with referrals to the legal teams. So I shifted my dissertation project to make an argument about the form of historical scholarship and intend to pursue the computational analysis of the images now that I’ve finished.

What are your future goals in terms of publishing your research? Are you planning to adapt any part of your dissertation for publication in print?

CS: It’s a great question with no clear answer. While the dissertation-as-proto-monograph pipeline is well established, there isn’t something similar for digital projects. I’m committed to maintaining the project in its digital form, rather than try to pull a book out of it, so I’ve been in conversation with several university presses about the possibility of publishing it as a digital monograph. I’m working on a couple of journal articles, both methodological and content-centered, related to the project. And I’m pursuing conversations with experts in fair use and copyright to see how to untangle the mess and build a fair use case for the display of the images. Much hinges on that last issue.

What are your future goals in terms of career? How have potential employers reacted to your digital project?

CS: Currently I’m the academic technologist for instructional technology at Carleton College, and I really enjoy being in a role where I can collaborate with faculty and students on research and curricular projects. I see myself continuing on a path where I can blend my interests in critical digital pedagogy, humanities research, and technology. How exactly that manifests depends a lot on how colleges and universities invest, structure, and support digital work going forward. So far, potential employers have been intrigued by my digital dissertation as a thing in itself, and it really opens up conversations around a lot of key issues for history, digital humanities, and digital scholarship writ large.

What advice would you give to graduate students trying to determine whether digital would be a good format for their dissertation project?

CS: I think going back to the research questions, over and over, really helps ground the question of “is this a good fit?” I crafted a compelling argument for my committee that my dissertation needed to be digital because it was rooted in the scholarly fields with which I engaged. I think that’s why I didn’t get any negative pushback. Open communication is key: be explicit with the faculty you’re working with to calibrate expectations. Doing a digital dissertation is quite different from work that is typically discussed as digital history or digital humanities, because it is a requirement for being credentialed in the field. The collaborative ideals of the digital history and digital humanities communities are in tension with the existing model of recognizing the dissertation as the work of an individual scholar, which is important to keep in mind throughout the process.

The project is currently password protected, but access is available by contacting Celeste Sharpe via email (csharpe@carleton.edu).

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.