“Historical events do not occur in a spatial vacuum; they take place in buildings and landscapes, and are in turn shaped by these environments,” Swati Chattopadhyay wrote in the January 2014 issue of Perspectives on History. “Understanding of all history, therefore, necessitates engagement with the history of architecture: the study of buildings, cities, and landscapes, from the smallest to the grandest, as the material documents of history.”

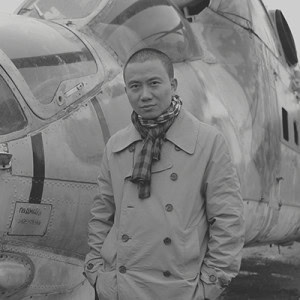

This week the 2014 Venice Biennale and its associated International Architecture Exhibition will open. Sixty-six countries will participate by examining their encounters with modernity in the last hundred years. Over Skype, curator Jiang Jun told me about his vision for the Chinese pavilion.

Rem Koolhaas, the curator of the 14th International Architecture Exhibition, chose the topic and title, “Fundamentals,” for this year’s exhibition. For Jun, who is an associate professor in Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, what is fundamental to Chinese architecture is not fundamental to Western architecture. China’s pavilion will focus on the philosophy behind China’s traditional architecture, and how it contrasts with modern Western design. Jun looked at Chinese architectural history and extracted a philosophy of design that, he argued, can be applied to architecture today. “When we are discussing what is changed within the previous 100 years,” he said, “What is even more important is what is unchanged in the past 4,000 years. Absorbing Modernity is about the ever changing, while Fundamentals is about the never changed.”

In the beginning of the 20th century, Chinese students who came to the United States to study architecture returned to China and introduced Western architectural concepts to the Chinese landscape.* Jun described the contradictions that resulted in modern Chinese architecture by comparing the archetypal Chinese garden with the typical Western garden. The “Chinese garden is the spatial expression of their understanding of the universe,” said Jun. “The Western garden, the garden before the modern architecture movement, is more about geometric design, about the aesthetics of the geometry. The difference lies in the different fundamentals: one is based on nature and one on science.”

When Chinese architects began designing buildings in the Beaux Arts style and following the Chicago school of architecture, nationalists welcomed the new styles of building because they sent the message that China can be powerful and economically independent, and surpass colonial powers. New influences did not only come from America. The Soviet Union was another source of inspiration for Chinese architects. The new styles of building meant that the process of building would also change.

In traditional Chinese architecture, Jun pointed out, most of the blueprints of buildings were drafted onsite as the building was being constructed. This is because each building was part of a cluster; its location and orientation were relevant to its use and users. “We have a fractal definition about the whole Chinese life,” Jun explained, “from object to family to community to city to country to the world, to the universe, and each is defining another.” This process began to be replaced by the Western process of building.

The traditional Chinese system of architecture is integrated, interrelated, and interdependent, said Jun, and the new system is not. “What we want to extract from the philosophy [of traditional Chinese building] is universal value, not only for Chinese but for the world,” said Jun. These values include “relevance, sustainability, freedom with respect for nature, doing something unlimited within limited space … . We think they should be there in the future. The form is already changed, but the imagery stays familiar, which mediates the tangible form and the intangible philosophy.”

The Chinese pavilion at the Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale is open from June 7 to November 23, 2014.

* The process continues today, in different forms. In the March issue of Perspectives on History, Jan Goldstein, wrote about China’s demand for professors and the experience of her stepdaughter, who holds a PhD in architectural history and now teaches in Suzhou.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

-300x208.jpg)