Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus has just retired elephants from its traveling shows, two years ahead of a previously announced schedule. On the first of this month—May Day—six of the Ringling elephants went through the motions for one last show in Providence before being shipped back to the company’s housing facility in central Florida, the Center for Elephant Conservation (CEC). Liberated from a schedule of travel and tricks, they will live with several dozen other elephants owned by the circus’s parent company, Feld Entertainment. Faced with constant public criticism and declining revenues, the company really had no choice but to reinvent its shows sans elephants.

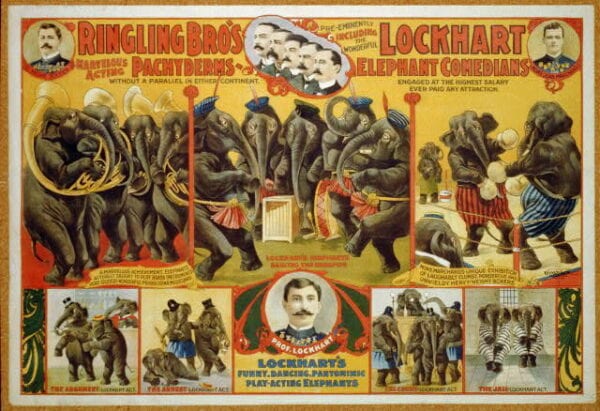

A poster from Ringling Brothers featuring elephants as attractions (1899). Credit: Library of Congress

It could be easy to be nostalgic about this moment in history. After all, Ringling Brothers is the last American circus to own a large herd of elephants. Just a handful of smaller shows holding one or two elephants continue working these creatures, and they are limited by many city and county bylaws prohibiting exotic animal acts. Consequently, it appears that the 200-year window in which Americans pioneered and popularized elephant acts as an iconic part of circus entertainment is closing.

It could also be easy to become complacent at this moment in history, as some concerned members of the public will if they believe that having elephants off the road will change the company’s instrumentalist view of these endangered creatures. Take a look back at the history of elephants in America and we find that, in the United States, elephants have always existed solely as a function of the commerce in exotic animals. On this continent, living elephants have always been perishable property put to work in our interest.

Beginning in the 1790s, men drove juvenile elephants from town to town as mobile animal exhibitions. It was a cost-efficient business as elephants fed and moved themselves, but these babies all died within a few years. Thereafter pairs and trios of juvenile elephants worked in traveling animal menageries that featured other tethered and caged animals who bumped and jostled over the rutted and muddy roads of antebellum America. Those elephants also died young, from mysterious illnesses, neglect, or mismanagement.

After the Civil War, combined circuses featured acrobats, trick equestrian riders, exotic performing animals of all kinds, a midway, gigantic broadside advertisements, a big top tent, and all the other trappings of the modern show, including herds of elephants numbering up to 25 individuals. The stereotype of a decorated, saluting elephant with trunk raised in greeting became the icon of the modern circus, which was the most complex and boldest mass entertainment Americans had ever known. Since elephants would not reproduce in captivity, the industry drove an elephant importation boom that lasted into the 20th century. Most of those elephants died before middle age, from illness, neglect, or, increasingly, because they were killed by their managers as they neared adulthood and became unmanageable. Certainly, the industry consumed juvenile elephants with abandon.

After the 1941 Disney film Dumbo empathized with captive elephants, Ringling Brothers and most circuses purged males from their elephant herds, also resorting to selling similarly unmanageable adult females to the growing network of city zoos and trained animal ranches in the nation. Mid-century want ads in an industry newspaper, Billboard, attest to the sad traffic in elephants in those years, as circuses and freelance animal suppliers bought and sold as necessary. In January 1955, for instance, one ad read: “ELEPHANT FOR SALE. One Elephant too many. Large, gentle. Good single routine. Pushes, pulls. Cheap for quick sale.” Meanwhile, to weather the challenge of television, circuses large and small transitioned away from railways and big tops to truck convoys and sports arena performances, reducing elephant herds down to 10 or less in order to reduce costs.

Although many people had publicly criticized or privately disliked circus elephant acts for almost two centuries, by the 1990s, electronic media gave the public unprecedented venues for research, communication, and organization against animal exploitation. Many argued for the intrinsic value of elephants as endangered species: beings with a right to independent lives regardless of their utility to humankind.

The circuses, in response, mounted a counter-narrative justifying the capitalist view of exotic animals as raw materials improved by captivity. Around 1995, some inside Feld Entertainment proposed that, in fact, the company had been in the animal conservation business all along. At the Ringling Brothers’ Center for Elephant Conservation, founded that year, trainers shackled company elephants and trained them to submit to human direction with pain/reward routines, a practice pictorially documented by whistleblowers and later confirmed by CEC staff themselves. Staff also began to employ artificial insemination (AI) technologies to impregnate teenage female elephants (breeding-age adult females routinely miscarry in captivity). Although the resulting newborns often die, staff worked to improve their procedures and have produced seven surviving babies so far. Indeed, like many city zoos, animal parks, and aquariums, Ringling spokesmen began speaking of their work in a commercial-zoological, quasi-conservationist mode, claiming that the CEC was managing an endangered elephant gene pool.

Since not headed to a sanctuary where they could decide when, how, or whether to interact with people in a commerce-free, nontechnological context, at the CEC, the Ringling elephants will continue to contend with being monetized as breeders. They are evidence of the ongoing privatization of wild animals facilitated by human-driven habitat destruction and climate change. Hence, here is the larger question that actually confronts Americans now: what is the place of wild and exotic animals in the 21st-century world, and who decides?

Legally speaking, elephants remain property in the United States and owners can put them to work in any way with minimal oversight—especially since the CEC is not open to the public. There is little indication the zoos and exotic animal ranches like the CEC will relinquish control of the precious and dwindling animal capital they control (the recent SeaWorld ban on orca capture and reproduction notwithstanding). This is especially so if we continue to destroy elephants and their habitats abroad. As long as those who own these creatures see how they are endangered in the wild, they will insist animals like elephants are too valuable not to be someone’s property, for their own good and ours.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Susan Nance is associate professor of US history and an affiliated faculty member at the Campbell Centre for the Study of Animal Welfare at the University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada. She is the author of various books and articles, including Entertaining Elephants: Animal Agency and the Business of the American Circus (2013).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.