Our divided times are bad, indeed, but have you heard about the late Middle Ages?

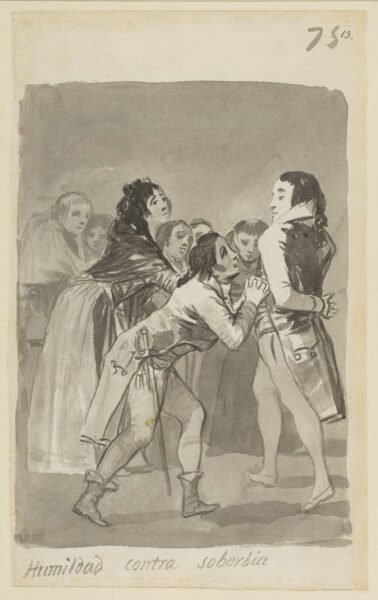

In a drawing by Francisco de Goya, Humility approaches Pride. Metropolitan Museum of Art/public domain

Jean Gerson (1363–1429), chancellor (aka the medieval provost) of the University of Paris, lived during unbelievably divided times. His entire career was framed by the Hundred Years War that raged about 1350 to 1450 between the superpowers England and France. During that time, a civil war split France as family factions competed to control the mentally ill King Charles VI, who reigned from 1380 to 1422. There were also two popes—one in Rome, one in Avignon—from 1378 until 1409, when a third papal line competed for power for nearly another decade. Not to mention that the Black Death kept reappearing every generation or two.

How Gerson navigated a world torn apart by politics, religion, and disease—sound familiar?—offers a lesson for today. In the midst of partisanship, he called for partnership. And he did it by recommending everyone act a bit more humbly.

Right in the middle of this turmoil, in a series of writings around 1400–1402, Gerson kept returning to humility. Gerson believed a humble attitude would help you understand that you didn’t know it all. Engaging with others—be they French or English, supporters of this or that pope, or even followers of another faith—was not intended to win or to convert or to convince, but to learn. The key was to seek out not what was different but what other perspectives they shared. Gerson was all about a medieval Venn diagram.

The key was to seek out not what was different but what other perspectives they shared.

It’s OK, Gerson taught, to shut up and listen to what others might teach you. This he called intellectual humility. As he said in a sermon in 1401, after talking about submitting to authority, “the other manner of humility is in the intellect, when we submit our knowledge and our own judgement and reason to the judgement and reason of another.”

Discretion allows for flexibility, allowing a person’s opinion to be malleable. That doesn’t mean wishy-washy or unprincipled. But faced with better information and the skill of making distinctions, a person can humbly admit that his original position was not complete. As Gerson put it, “By this flexibility I understand a readiness to believe in counsel, which is the daughter of humility.” Though he was writing here in a treatise about trying to discern between true and false spiritual revelations (De distinctione verarum revelationum a falsis), we can certainly hear the echo of Abraham Lincoln calling in his first inaugural address in 1861 for us to follow the better angels of our nature.

For Gerson, one of those better angels is the lost virtue of humility. If we think of ourselves not as know-it-alls but as pilgrims, then we’re freed from needing to have all the answers. Humility and discretion particularly work against the temptations wooing those among us who are sure we’re right. This produces the zeal, condemnation, and apocalyptic rhetoric ringing through what should be the marketplace of ideas but is instead a shooting gallery.

Humility takes the edge off self-assurance. There should be room for doubt, which drives you to seek out people who can see further or more widely than you can. Discretion counters ego, certainty, and pride. Gerson believed that pride produced vanity and striving for fame, which in turn caused envy and produced competition. Pride blocked the patience he believed necessary to think carefully and deeply about a topic. Pride also blocked introspection and prevented a person from being open to the good judgment of others.

Once reason ran unchecked by listening to others, it naturally led to excess and disorder. Think of our own confirmation bias closets, our echo chambers, our declarations that we’re more American or Democratic or Republican or Jewish or Muslim or Christian than others within our own tribes. Ours is the true faith—be it religion, politics or, as we have now, religious politics (or is it political religion?).

Gerson also saw humility as a prize virtue in working toward helping each other. He learned from Plato and Aristotle that community and education should build good citizens and public servants. Some professors and students used fancy words to sound smart, but all they did was confuse people. Instead of doing good, they sought attention. They didn’t want to solve a problem for many, they wanted to win an argument—or at least to shout more loudly than their opponents.

Full of pride and arrogance, Gerson saw smarmy professors and students as playing word games. He took direct aim at vain curiosity in his reform of the curriculum at Paris, Contra curiositatem studentium (Against the Curiosity of Scholars). Not only is there no room for nuance, but we miss the point—which is not just to argue about problems but to find solutions. “Let us learn not so much to dispute as much as to live,” he suggested, “remembering our goal.” He would have been annoyed by professors, pundits, and politicians looking for clicks and screen time instead of offering common good answers. As he criticized his faculty: “They became futile in their thinking and their senseless minds were darkened.”

What does rivalry accomplish but a competition of one-upmanship?

Gerson was also concerned in this treatise about the factionalism that can result from a lack of humility. When one group of students believed their idol had the brilliant answer, they stopped listening to other voices. They sought competition and contradiction with the goal of raising themselves and their mentors up by knocking others down. What does rivalry accomplish but a competition of one-upmanship: “Some people get angry and are eager to contradict.” This kind of pride hunts for differences and triumphs that produce partisanship; it does not seek points of agreement that produce partnership.

Blessed are the smug? Because someone thinks they are completely right and the other side is completely wrong, the game is already over. Everyone loses. The smug make themselves small-minded. They trust so much in their own counsel that they cannot even see someone else’s position, let alone defer to another’s better experience or expertise. The tool to fight back is humility and an openness to other people’s ideas. As Gerson put it, “Even small-mindedness itself, which seems to rebuke pride, greatly embraces pride within itself, while it prefers its own sense and judgment to that of his superior; while, moreover, he prefers to obey his own rights rather than those of others, which can and should properly be obeyed.”

Gerson’s goal is to meet in the middle—to compromise, not to compete; to get things done, not to shine the brightest; to solve a problem, not to win a game. What’s wrong with that?

Christopher M. Bellitto is professor of history at Kean University. His latest book is Humility: The Secret History of a Lost Virtue (Georgetown Univ. Press, 2023).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.