In an election season already bursting with unpredicted twists and turns, the decision by President Joe Biden to withdraw from the presidential race has guaranteed that the 2024 election will be scrutinized carefully for its historical significance.

President Joe Biden’s withdrawal from the presidential race has guaranteed that the 2024 election will be scrutinized carefully for its historical significance. LollyKnit/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

No incumbent president has ever withdrawn from a race so late in the electoral season, and few have faced such formidable paths to re-election. But winning a second term, while generally portrayed as the norm, is far from a certainty. More than half the incumbents over the past half century have been elected to just one term: Lyndon Johnson, Jimmy Carter, George H. W. Bush, Donald Trump, and now Joe Biden. In addition, Gerald Ford never won his own term as president, being defeated in his 1976 run after having succeeded Nixon in 1974.

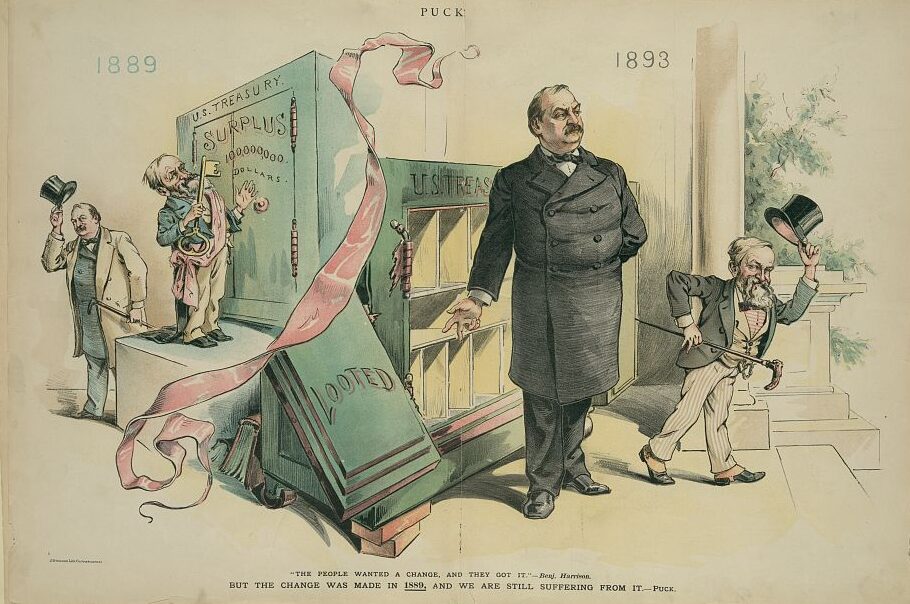

During the antebellum era, single-term presidencies were also common. Indeed, from 1837 until 1860, all presidents—Van Buren, Tyler, Polk, Fillmore, Pierce, and Buchanan—served only a single term despite the earlier trend of seeking and winning re-election.

Additional parallels between that period and our own cause understandable unease. Prior to the Civil War, decades of sectional, economic, and cultural division had riven deep cleavages in American politics and society. The South believed that abolitionists and their allies in Congress were determined to uproot the labor structure of the southern plantation economy and dismantle the rigid slave system that had undergirded southern society for two centuries.

Many northerners, while neither ardent abolitionists nor proponents of full equality for Black Americans, were repelled by the dehumanizing nature of the “peculiar institution” and were committed to preserving western lands for white settlers by stopping slavery’s spread and, increasingly, to eradicating it where it already had taken root. Legislative efforts in Congress and rulings by the courts created only brief periods of tranquility, and after 1850, it became increasingly evident that the integrity of the nation itself was at imminent risk. Failure to resolve the intractable divisions over slavery, immigration, border policy, western expansion, and state nullification perpetuated brief tenures at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

Some contemporary soothsayers darkly predict the possibility of a second civil war or its equivalent arising from our current political turbulence. There is little disputing that Americans have aligned themselves into warring political camps that disagree not just on the prescription for remedying our national ills but what those ills are and whether people in the other party can be trusted. A 2019 Atlantic article, ominously entitled “How America Ends,” reported on a study that found that 35 percent of Republicans and 45 percent of Democrats believed that “members of the opposing party are like animals, that they lack essential human traits.” Little has occurred since then to suggest that prospects for harmony are improving.

There is little disputing that Americans have aligned themselves into warring political camps that disagree not just on the prescription for remedying our national ills but what those ills are and whether people in the other party can be trusted.

Many developments have contributed to this deep divide. In some cases, these historical changes were foreseen: the implementation of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts in the 1960s enfranchised millions of Black voters who flocked to the Democratic Party, leading millions of white conservative Dixiecrats to revitalize the Republican Party, both in the South and nationally. Lyndon Johnson foresaw the electoral problems this realignment presented Democrats, telling his aide Bill Moyers, “I think we just delivered the South to the Republican Party for a long time to come.” In 1969, in the wake of George Wallace’s 1968 independent campaign and Richard Nixon’s “Southern Strategy,” Kevin Phillips anticipated an “emerging Republican majority” fueled by cultural conservatives fleeing the Democratic Party.

Other innovations were less recognized contemporaneously as promoting such tectonic movement in American politics. The explosion of social media and weakened standards for media broadcasts following repeal of the Fairness Doctrine in 1987 all but eliminated the traditional barriers that filtered extreme views from easily entering the political marketplace. A dangerous weakening of judicial and legislative constraints on campaign fundraising enabled the massive expansion of special interest money that rewards more ideologically extreme views while punishing those who engage in the bipartisan collaboration that had been rewarded in less polarized times.

Among other developments, these transformations helped shape many high-visibility political issues less as negotiable policy stances and more as immutable “rights,” insulated against the compromise inherent in legislative deliberation. Civil rights, gun rights, abortion rights, religious rights: deviation from “orthodox” doctrine subjects politicians to well-funded challenges both within their party and in general elections.

These transformations helped shape many high-visibility political issues less as negotiable policy stances and more as immutable “rights,” insulated against the compromise inherent in legislative deliberation.

In the antebellum era, the parties also proved incapable of finding common ground to enable them to avert the path leading to civil war. Eventually, by 1856, one of those parties, the Whigs, fell apart and a new political party emerged—the Republican, which was unwilling to make concessions to the South on fundamental issues like the expansion of slavery. In just one election cycle, this new party captured the White House and southern states began seceding from the nation.

In 2024, the emergence of a competitive third party seems slight; in this highly polarized environment, there is scant evidence of a sizeable constituency for a party whose strategic objective is to promote compromise. Indeed, many current third parties favor even more extreme views than those they criticize. Innovations like ranked-choice voting or proportional representation may offer some options for encouraging candidates to embrace less ideologically rigid views, but their effects are thus far indeterminate. More sweeping reforms like altering the unrepresentative structure of the Senate, limiting Supreme Court terms, or abolishing the Electoral College in favor of the popular election of the president are far less feasible given the challenges of amending the Constitution.

Given the instability of the nation’s politics over the past decade, the smoothness with which Vice President Kamala Harris secured the Democratic nomination after Biden’s withdrawal is remarkable. Had Biden withdrawn earlier or not sought renomination, one might reasonably have anticipated a more crowded and disputatious primary campaign reflecting the multiple factions within the party. The president’s late withdrawal and the unwillingness to bypass a qualified sitting vice president, a woman of Black and Asian heritage, effectively eliminated such a challenge.

This is not the Democrats’ first seamless transition in recent years. In 2022, House Democrats achieved an orderly switch from the two-decade leadership of Nancy Pelosi to Hakeem Jeffries that may reflect a growing willingness to avoid intraparty fragmentation in light of the perceived threat of Donald Trump and the MAGA-dominated Republican Party. Republicans in Congress have not been so fortunate. The House GOP conference has been riven by deep ideological fissures since 2011, resulting in four speakers (2015, 2016, 2023) and hobbling the party’s ability to find policy consensus and compelling concession to Democrats to pass essential legislation.

Like Buchanan’s victory in 1856, the outcome of the November election could well add accelerant to the partisan fires. One can only hope that the anxieties about the future of our democracy stoked by the current campaign instead promote a demand for greater national unity and a search for common purpose once the current election season ends.

John A. Lawrence is a visiting professor at the University of California Washington Center and author of Arc of Power: Inside Nancy Pelosi’s Speakership, 2005–2010 and The Class of ’74: Congress after Watergate and the Roots of Partisanship. A veteran of 38 years on Capitol Hill, he served as Speaker Pelosi’s chief of staff for eight years.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.