I don’t think I’m alone in saying that this was a Black History Month to remember. With the intense racial reckoning taking place throughout the United States, not only are historians reconciling our racial past with our present, but we are striving to give better context to the momentous events of the past year. For some scholars this is being achieved through deep historical study of the United States’ racial roots. As one wades into the scholarship of just the last decade, replete with wonderful work including Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, which was groundbreaking a decade ago; Peniel Joseph’s The Black Power Movement and biography of Stokely Carmichael; Quito Swann’s Black Power in Bermuda; comprehensive anthologies celebrating The New Black History; the remarkable books that make up the New Black Studies series from the University of Illinois Press; and the emerging work in antiracist studies, I cannot help but sense that the work feels new, not just in chronological terms, but in its very novelty.

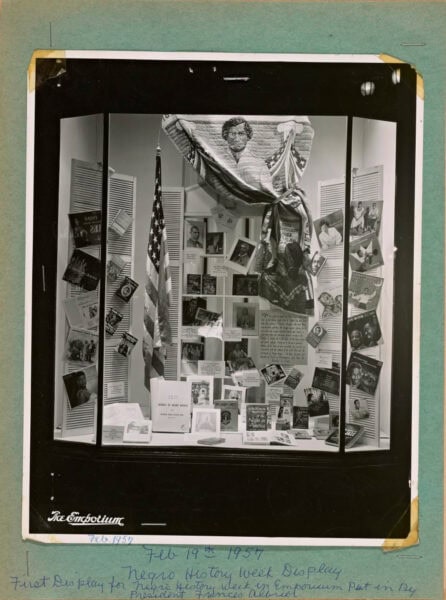

Scrapbook page compiled by Frances Albrier, president of the San Fransisco chapter of the National Council of Negro Women, documenting the group’s Negro History Week display installed at The Emporium in 1957. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Frances Albrier Collection. 2010.60.1.6.

The feeling crystallized for me during the Conference on Latin American History’s Presidential Panel on “Anti-Blackness and History,” held virtually during the CLAH annual meeting in January. Amidst emotional testimonies of Black historians recounting painful past field research experiences, juxtaposed against an immediate call for Latin Americanists to deploy Black history to combat both racism and various legacies of anti-Blackness, I had a nagging sense that writing Black history can slip easily into a time warp. Even as major advances in scholarship on the Black experience are made, just how much can they make a difference in some countries, where national identities are heavily predicated on racial mixture, thereby causing the study of Blackness to be continually and repeatedly registered as a surprise? Reflecting on this in the Zoom room, I found myself asking two questions: Just why do some fields age, while others seem to remain forever young? And what are the consequences of the discrepancy, especially in a moment where we are leaning heavily on Black history to help a nation heal?

Looking into the African diaspora sometimes helps us frame questions about American culture. Racial mixture’s influence on how the United States regards itself as a nation is different from the comparable dynamics in Latin America. But I wonder if a continual packaging of Black history as “new” is something both African American history and Latin American studies need to reconcile?

David Varel’s recent article on Lawrence Dunbar Reddick’s career, published in the February 2021 issue of Perspectives, suggests so. Reddick challenged the so-called New Black History of the 1970s. As professional interest began to soar, Reddick pushed back, highlighting a legacy of previous work. Years before being embraced by the academy, scores of unsung African American historians toiled in the shadows, tilling the soil, making Black history ready for the moment of sudden, Civil Rights movement–inspired discovery. While new methodologies, changing political contexts, and the integration of broader swathes of practitioners might have generated a freshness to Black history in the 1970s, that was not sufficient to recast it as new.

Why do some fields age, while others seem to remain forever young?

Although being new can be exciting, and can legitimately advance scholarly conversations, there are real dangers in perpetual disciplinary novelty. In fields that have long been marginalized, such newness can stretch well beyond its true half-life, stunting a field’s growth. Newness recreates itself, insidiously (and often unintentionally) limiting the depth of a field because in the constant clamor for the next stage of newness, the field’s legacy and depth of historical debates can get curbed and sidelined. Consequently, rich historical conversations with previous generations of work may not get their due in an errant chase for being recreated as new. Call it a type of arrested development.

Denied the ability to properly age, a form of academic infantilization can ensue. Juxtaposed against fields with more “tradition,” the full value, critique, and contributions of the field may not be as strongly felt. And historians working in Black history, while certainly in demand on the market for being avant-garde, may not always get the opportunity to ascend the same ladders of pedigree as their counterparts. Equally, hiring practices and financial support of the field can be more susceptible to cyclical fluctuations, as the field’s questions may be seen by outsiders as responding more to the crises of the moment than to deeper, endemic academic questions and concerns.

I hope I’m wrong about this perception of newness.

Being seen as perpetually new can also create challenges, not unlike entering into the shallow end of a swimming pool, when it comes to conducting research. The need for researchers to work with a fuller historiography, to grapple with a complete canon, or to engage with complex perspectives on various sources can be more easily sidestepped in the name of offering a fresh perspective.

Black history in all of its dimensions, and in all of the areas of the world where it is studied, is unusually rich and fertile. I hope I’m wrong about this perception of newness. But I worry. The recovery of that history often entails creative approaches to sources that explore registers of meaning, sometimes well beyond what the documents offer. The artistry involved has taken time to evolve, and these long pathways contribute valuably to current practice. While there are dark legacies in that history borne by racism that we must work hard to reconcile, I’d like to see the ability for the field to age, and to age gracefully. As we celebrate Black History Month this year, and as we celebrate over 100 years of the Association for the Study of African Life and History, I say: please, let’s allow this field to mature fully into its own.

The author would like to thank Erika Edwards, Celso Castilho, and Stefan Wheelock for their valuable input in helping refine this essay.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.