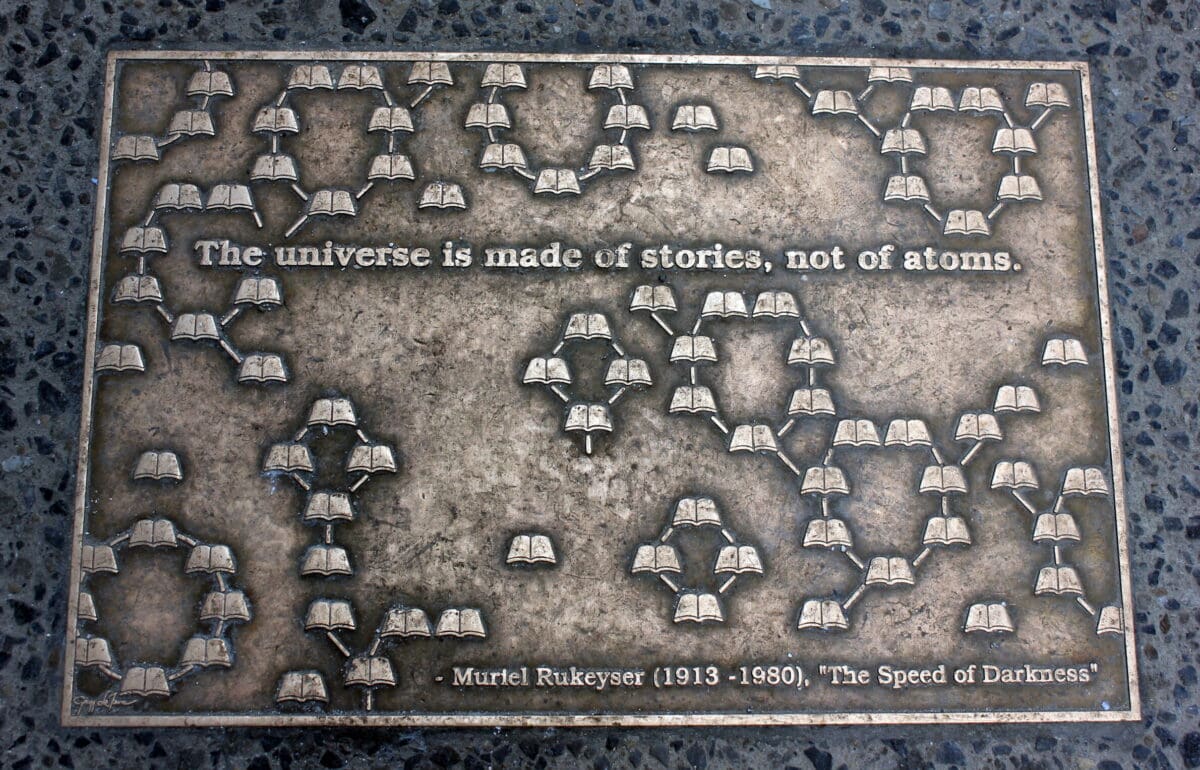

“The universe is made of stories, not of atoms.” In January, I had a quintessential New York moment, pizza in hand, as I stood reading this Muriel Rukeyser quote engraved on Library Way outside the Main Branch of the New York Public Library. I had wandered there upon the advice of Lendol Calder (Augustana Univ.) during my first session of the AHA annual meeting. Rukeyser’s point, of course, is to put stories at the forefront of the daily work that we do in understanding the world around us. As a high school teacher, I found in her words a valuable framework for my role as an educator. I carried them with me for the rest of the weekend as I worked with the AHA’s inaugural K–16 Content Cohort to consider how stories help center resilience in the history classroom.

The New York Public Library’s Library Way includes poet Muriel Rukeyser’s words. Heike Huslage-Koch/Wikimedia Commons/public domain

Teachers from across the country, and at all levels of education—including me—met to explore the theme of “resilience and history education.” Throughout the weekend, the K–16 Content Cohort convened for several seminar-style discussions on the topic, as well as to attend recommended panels and workshops that specifically examined resilience, teaching, or the intersection of the two. The cohort provided crucial support and connection for its attendees, as well as the intellectual framework and space to think critically about the work we do as educators.

This new format addressed challenges I have experienced as a high school teacher attending big academic conferences like the AHA: the breadth of such a large event, and the accompanying isolation. At previous meetings, K–12 teachers could choose from a selection of panels that spoke either to their individual academic pursuits or, occasionally, to teaching. It was rare to find panels and workshops that did both, and rarer still to meet colleagues with whom you could share a discussion. But the K–16 Content Cohort set out to address both issues, with a track of recommended sessions and events, private sessions for our group alone, and a built-in community to travel with through the weekend.

Participation in the cohort started even before the conference. On an AHA Communities message board, cohort members could introduce ourselves and make connections before January. Here, I found a diverse group of high school teachers, professors, and history professionals working in both the public and private sectors. Several weeks before our arrival in New York City, the cohort received three articles on resilience to read in preparation. The articles—“Genealogies and Critiques of Resilience” by Yoav Di-Capua and Wendy Warren, “Critical Investigations of Resilience: A Brief Introduction to Indigenous Environmental Studies and Sciences” by Kyle Whyte, and “The Stories We Tell” by Lendol Calder—encouraged participants to think about resilience’s evolving definition, the forms it can take over time, and what it can look like in the history classroom. Calder’s article introduced the concept of stories as an essential component of resilience—a focus that I carried with me to the conference.

The cohort provided crucial support and connection for its attendees.

Together, these readings formed the foundation for our three cohort meetings over the course of the weekend. The introductory event on Friday was a panel discussion on resilience and history education, with presentations from researchers and educators at the secondary and postsecondary levels. The second meeting was a cohort seminar on Saturday chaired by Brendan Gillis, AHA director of teaching and learning. This event gave the cohort our first opportunity to work alongside one another as we developed individual and collective understandings of what resilience can look like in history teaching. The final meeting on Sunday allowed us to share and discuss assignments designed by participating teachers that demonstrated resilience. Each of the three meetings created a unique space to think about the theme of resilience as central to the work of history educators, and helped give us a foundation for the other sessions and events that we attended throughout the weekend. Throughout these meetings, storytelling served both as a topic of discussion and as a means to facilitate other lessons on resilience.

For those in the cohort, storytelling brought a strong sense of our connection to one another, which is another essential component of resilience. We heard from our peers in Delaware and Harlem at the opening reception for K–12 teachers about their hard work teaching contested history. We had formal and informal discussions with other members of the cohort during our daily meetings. We told tales about disgruntled parents and students, about assignments and lessons gone wrong and those gone gloriously right, and about the stories from the past that we love to tell our students. As we talked and shared, we forged connections with one another. When one cohort member lamented the politicization of history, and the personal toll it took when directed at educators, we were able to empathize with him and provide comfort. These relational moments bolstered our individual resilience, as they affirmed that we were not alone in our experience, and that there was a professional community holding space for the ways that teaching history can lead to moments of tension, turmoil, and frustration.

Telling stories to one another about our experiences and the histories we each hold dear also facilitated individual reflection and learning. The panels and workshops recommended for those in the cohort to support our exploration of resilience each emphasized the importance of continually examining how and what we teach. Sessions such as the K–16 Educators’ Workshop: Finding and Elevating Missing Voices from the Past and Teaching History Writing in the Age of AI used both the expertise of presenters and the stories from participants to encourage conversations about the craft of teaching. Educators of all levels shared stories about successfully finding primary source images for niche research projects on the Library of Congress website, organizing student writing workshops that yielded impressive results, and integrating AI prompts into grading criteria for smoother evaluation. With each story came an opportunity to reconsider our own practices and how we might improve.

Similarly, in our seminar discussions, we learned from each other. Amie Wright (Carleton Univ.), a PhD candidate and instructor, spoke of how using graphic novels and comic books in the classroom could make complex stories from the past more accessible. Kayanna Adams (Field Kindley High School, Kansas) shared her success in engaging students in discussions about protest through the film Iron Jawed Angels, which depicts the US suffrage movement in the 1910s. Hearing about these experiences and sharing resources with other educators encouraged us each to consider our own practices. Through these stories, it became clear that striving to improve our teaching can be its own form of resilience.

This weekend of telling stories about our shared work and passion had reconnected me with my professional self.

While stories facilitated our connections to each other, and our reflections on our teaching, it was the cumulative experience of the K–16 Content Cohort that bolstered both our individual resilience and that of the teaching profession at large. The weekend provided an indispensable opportunity for me to think deeply about the work of history teaching. At its close, I was profoundly moved by how this weekend of telling stories about our shared work and passion had reconnected me with my professional self. Teaching students to know themselves, to question and affirm that sense of self, and to empathize with others through stories is why I love both the historical discipline and my job. Stories, I’m convinced, are what matter. Without the opportunity for stories to bring colleagues and concepts together at previous conferences, I often struggled to find my place. The opportunity to connect with colleagues who value stories as much as I do, and to discuss those stories in depth, was a balm to the isolation and exhaustion I have been navigating as I near the middle of my career. As such, I returned to my classroom following the annual meeting feeling reinvigorated for, and more resilient in, my teaching.

In addition to the experience of individuals, the creation of the K–16 Content Cohort and its initial success reflects how our discipline continues to adapt and find new ways to be resilient. The cohort created an intellectual space where the work of reflecting on history education at all levels could be done in collaboration with colleagues who value the interconnected nature of scholarship and teaching. Because of this, AHA25 provided a professional development opportunity far and away more effective than those typically offered to educators in the K–12 sector and unique to professors who spend their time on college campuses. We are all better off for this collaboration. The more we come together as historians and teachers, the stronger—and more resilient—we become.

The K–16 Content Cohort created an essential space within the AHA annual meeting for teachers at all levels. The theme of resilience and history education was a framework that helped us better understand the art of teaching history. Coming together to share our own stories and the stories of the past that we love, we forged a strong community where we could reflect on our own practices and learn from one another. The panels, workshops, and seminars worked together to affirm, challenge, and expand our professional practices far more than any conference targeted at a single level of history instruction could. The work that we did together set a precedent that history teachers at all levels have a place at the AHA annual meeting. It is in this coming together that the field will continue to build its resilience—no doubt an essential mission in the years to come.

Megan Porter is a teacher and history department chair at Lenox Memorial Middle and High School in Lenox, Massachusetts.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.