On August 15, 1502, Christopher Columbus’s men came across a Chontal Maya trading canoe near Guanaja, an island off the Honduran coast. Describing cargo carried by the native population in his account of the voyage, Columbus’s son Ferdinand included “some almonds that the Indians in New Spain used as currency.” He seemed mystified that “when some [almonds] fell to the floor, all the Indians scrambled to pick them up as if an eye had fallen out of their heads.” Such is the first recorded European mention of cacao, and the only reference in Ferdinand’s account. Other European chroniclers paid little to no attention to cacao and chocolate. As a currency, cacao never held the same value as silver and gold. As a cash crop, it was eclipsed by tobacco and, later, by sugar and coffee. And as a food, chocolate could never compete with potatoes, maize, or beans.

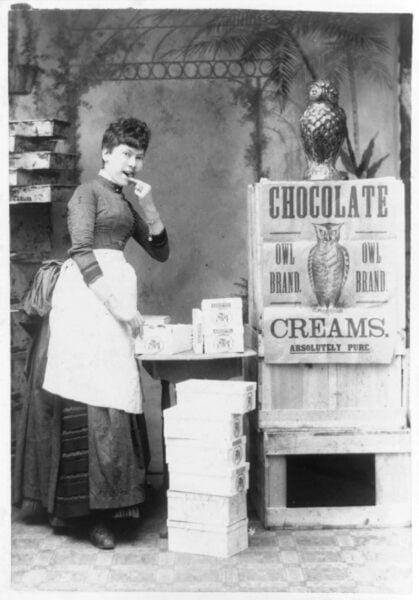

As chocolate companies have relied on samples to attract new consumers, chocolate tastings can engage students in the food’s history. Advertising cards for H. McCobb’s chocolates and cocoa/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Over the last two decades, interest in cacao and chocolate as objects of study has increased significantly. In my world history courses, I present them not only as discrete topics but also in light of their relationship with the societies they came into contact with. The study of ancient Mesoamerican civilizations acquires new meaning when students examine the spiritual and material role of cacao and chocolate among the Maya and the Mexica. Analyzing European discourses as they developed to justify or vilify chocolate consumption helps students understand the intellectual processes around the adoption of new cultural habits. The study of cacao production in Venezuela and Brazil offers valuable insights into the transatlantic slave trade. Focusing on legal and illegal cacao trading systems provides an opportunity to discuss important features of mercantilism. The Industrial Revolution becomes more relevant when students uncover the processes involved in manufacturing the modern chocolate bar. The expansion of cacao production into Africa serves as another example of the profound changes experienced by African societies as a result of European imperialistic aggression.

Cacao and chocolate become starting points to uncover changes and continuities in world history. In addition to lectures and discussion, I have turned an activity that students clearly enjoy—chocolate tasting—into an integral part of the course. The first exercise we do in each class session, sampling chocolate serves as both an icebreaker and a starting point for discussions.

Nothing is simple about transforming cacao beans into chocolate. Although newer technology has taken over the manufacturing side, the principles of chocolate making (fermentation, drying, roasting, grinding, and mixing) remain largely unchanged. As part of our discussion of Mesoamerican civilizations, students sample raw cacao beans, most for the first time. I suggest they focus not only on the taste but also on the bean itself. Students are surprised by the difficult process of peeling the beans and the bitter, gritty taste of the raw cacao. The exercise helps them appreciate the laborious process by which raw materials become edible, the complexities of chocolate making, and the degree of culinary sophistication and ingenuity required from those who “invented” chocolate. The bean and its novel taste prepare students for a discussion of the biology of the crop, the modifications chocolate has undergone to acquire its modern form, and Mesoamerican spiritual and material cultures. In conjunction with the cacao beans, students examine images of archaeological artifacts that depict cacao or chocolate consumption from the Maya period to the 16th-century Florentine Codex.

The first exercise we do in each class session, sampling chocolate serves as both an icebreaker and a starting point for discussions.

Mesoamericans enjoyed their chocolate mixed with water, spices, and sometimes honey. Most discussions of chocolate highlight changes to the beverage once Europeans adopted it, such as the addition of sugar and milk. However, Europeans still used the original chocolate recipe as described in the Florentine Codex more than a century after the conquest. As students sample two spicy dark chocolates, one with chili and one with black peppercorns, I ask them to focus on flavor but also to think about the ingredients and their places of origin. Despite the added spices, students are stunned by the similarities in flavor and surprised to learn that Europeans did not alter the taste of chocolate until much later. Our conversation usually centers on the spice trade and the global exchanges that followed the conquest of the Americas as part of the Columbian exchange. Spicy chocolates provide an opportunity to discuss the diffusion of new cultural habits in the context of imperial expansion and to understand colonization as a dynamic process involving mutual cultural interactions. In conjunction with the spicy chocolate, students compare recipes recorded in the Florentine Codex and those published by Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma in 1631.

Europe’s embrace of chocolate did not result in immediate changes to the Mesoamerican recipe. But during the 17th century, as claims of medicinal benefits paved the way for wider acceptance, chocolate became a symbol of status and opulence, and Europeans modified its recipe to suit their palates. For a discussion of preindustrial Europe and colonial empires, students sample semisweet chocolate with orange, berries, or almonds. I ask them to think about the use of ingredients with long histories in European pantries. They recognize this as the moment that marks Europe’s final appropriation of chocolate, thereby dispelling commonly held notions that Europeans rejected native foods or modified them immediately. Our discussion also focuses on the effects that changes in European consumption patterns had for cacao-producing regions. I rely on their knowledge of labor demands for cash crops and remind them of our prior discussions about the cacao bean and its biology, which provides an opportunity to examine colonial trading policies, commodity exchanges in the context of mercantilism, and the role played by stimulants other than coffee and tobacco in the transatlantic system. In conjunction with the semisweet chocolate sample, students watch a short clip about cacao cultivation and examine a series of maps that show environmental characteristics in Venezuela and Brazil, pre-Columbian patters of settlement in South America, cacao-producing areas in both regions, and the routes of the transatlantic slave trade.

Europeans enjoyed their chocolate as a beverage or in creamy desserts for centuries; the now ubiquitous chocolate bar is a modern invention. Chocolate acquired its contemporary solid form in the 19th century, as the Industrial Revolution transformed chocolate manufacturing into the snack we consume today. For our discussion on the Industrial Revolution—from new production methods to the invention of milk chocolate—students taste milk chocolate bars. I ask them to think about the ingredients but also about the food’s physical characteristics, which yields a tactile understanding of the changes in consumption patterns that resulted from industrialization. The chocolate bar provides an opportunity to discuss the impact of the Industrial Revolution on the manufacturing of common household foods, the creation of a mass market, and related changes in lifestyle and consumption practices. In conjunction with the chocolate bar, students examine a wide array of 19th-century advertisements as well as some vintage chocolate trading cards and small tin containers I have collected over the years.

Students recognize that the so-called “European” chocolates they consume are made with cacao from Africa.

The mechanization of chocolate production increased the demand for raw materials. The optimal area for cacao cultivation is 20 degrees north and south of the equator. Because the expansion in production occurred as Latin American nations were gaining independence, European manufacturers turned their attention to Africa. In the discussion around European imperialist expansion, students taste a “Belgian chocolate” bar. I ask them to think about the label. Almost immediately, they realize it refers to the place of manufacturing, as Belgium is located outside the cacao belt. This is usually the most successful discussion of the semester, as students recognize that the so-called “European” chocolates they consume are made with cacao from Africa. Our discussion revolves around the international division of labor propelled by the Industrial Revolution and the search for raw materials that prompted Europe’s Scramble for Africa. “Belgian chocolate” gives students an opportunity to see the expansion of cacao production in Africa in the context of European imperialistic aggression, as well as the impact that increased demand for cacao had on African societies in the 19th and 20th centuries. In conjunction with the chocolate bar, students examine images from São Tomé’s cacao plantations, excerpts from Henry Wood Nevinson’s 1905 report on labor conditions in the area, and newspaper reports on the early 20th-century Cadbury scandal. The sources provide a good foundation for the documentary The Dark Side of Chocolate (2010), which I show the week after, as well as our analysis of the 2001 Harkin–Engel Protocol, which aimed to regulate forced-labor practices on West African cacao farms. In fall 2024, I incorporated research conducted by the winners of the 2024 Nobel Prize in economics examining the long-term consequences of colonial institutions in modern societies.

Bringing cacao and chocolate front and center in world history is a way to illuminate intersections among American, African, and European societies. This approach forefronts the transformative effects that the crop and food had on the peoples who encountered them as producers and consumers. A commodity as ubiquitous today as chocolate encourages students to engage with the material in a relaxed atmosphere while simultaneously preparing them for the serious discussions ahead. It keeps them engrossed for the entire class session, as discussion questions and primary sources refer them back to their tasting experience, offering an alternative point of access to history by engaging the senses in ways that differ from other classroom activities. Chocolate sampling creates a bridge connecting past to present, brings students closer to the societies they are learning about, and serves as another reminder that history is a discipline that allows individuals and societies to know themselves better. More than anything, chocolate tastings are a fun and tasty way to make history come alive.

Patricia Juarez-Dappe is professor of history at California State University, Northridge.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.