The AHA annual meetings held in New York City are always well attended. Whether due to the large regional population, the ease of travel from other cities on the East Coast, or the many attractions the city has to offer, a NYC conference offers an experience like no other.

The AHA returned to the city this year for the first time since the pandemic. The meeting itself felt like a return to form, reaching nearly 4,000 attendees, a level unseen since 2020. And the AHA meeting continues to evolve, with its organizers on staff, committees, and Council looking for new ways to inject fun into the proceedings. With meetups of board game lovers, knitters, and readers; tours featuring queer history and “sinister secrets”; and more sessions on the program than ever before, there was a renewed energy in the conference hotels. We can recap only a handful of the weekend’s goings-on below, but these sessions and events reflect the excitement that infuses the historical discipline today.

—Laura Ansley, Whitney E. Barringer, Lauren Brand, Brendan Gillis, Lizzy Meggyesy, and Hope J. Shannon

From publishers to education groups, poster sessions to the headshot booth, the Exhibit Hall was the place to be at AHA25.

Ever Broader

Two years after the AHA issued the Guidelines for Broadening the Definition of Historical Scholarship, AHA25 included a number of sessions that highlighted the many ways that historians are continuing to answer that call.

Pulse Check: A Roundtable on the AHA’s Guidelines for Broadening the Definition of Historical Scholarship, sponsored by the AHA Council’s Research Division, acted as a check-in for historians to “reflect on the impacts and challenges of working within and implementing” the guidelines. These guidelines were “intended to encourage tenure and promotion committees to think beyond the creation of ‘new knowledge’ (i.e., monographs and journal articles) as the only viable category of historical scholarship,” and endorsed other forms of knowledge diffusion, such as textbook editing, amicus briefs, documentaries, exhibitions, op-eds, and more. Session chair Andrew McMichael (Auburn Univ., Montgomery) and panelists Steven W. Hackel (Univ. of California, Riverside), Jessica Marie Johnson (Johns Hopkins Univ.), and Lauren MacIvor Thompson (Kennesaw State Univ.) shared their experiences working within broader categories of scholarship and grappled with how they have incorporated the guidelines at the department or institutional level.

Hackel introduced the guidelines and acknowledged the difficulty of implementing the kind of change they call for. But UC Riverside has taken steps toward redefining success at the department level. Hackel assisted in creating his department’s document of what counts as scholarship and hoped that “all colleagues could see some aspect of themself in this document.” Rather than see it as a binding policy, he suggested instead that it be viewed as a consensus document of what should be valued. As Broadening becomes more widely used, the strengths and challenges have become evident. Yet Hackel shared some positive changes, such as colleagues having confidence that they can take on “untraditional” projects for which they would receive credit and that could lead to more grant funding, promotions, and other benefits. On the other hand, Hackel questioned the time it would take departments to create a post hoc peer review process and the logistics of applying the guidelines consistently.

Johnson had similar questions when she first read the guidelines. She was intrigued by the suggested categories of evaluation but was wary of the extra labor required for candidates to explain why what they do is scholarship, in some ways asking them to go above and beyond to legitimize themselves as scholars. She warned that this burden often falls heavier on people of color and those outside of traditional institutions. McMichael concurred, noting that the guidelines introduce unstated expectations between colleagues, and often “there is an inverse relationship between impact and credit.” The Broadening guidelines are a useful start, but flaws still exist in how they are practiced at the departmental level.

MacIvor Thompson, who recently completed her third-year review, spoke from experience on how Broadening has assisted her. Her review portfolio included traditional scholarship as well as contributions to the blog Nursing Clio, op-eds in popular news outlets, and amicus briefs. MacIvor Thompson was steadfast in asserting that this public-facing scholarship should be counted as research, rather than service. Broadening allowed her to frame these projects as having a noteworthy impact by elevating the status of her university with the public. This value of public-facing scholarship threaded throughout the discussion, as panelists acknowledged the need for historians’ work to go beyond the academy.

McMichael brought up more forms of potential scholarship to which the Broadening guidelines can apply, mentioning the AskHistorians community on Reddit. From the audience, a moderator of that forum, which has over two million users, explained the peer review process that their team uses to ensure that the historians who answer questions there are legitimate. Nontraditional scholarship such as this are exceedingly important in an age of disinformation.

There is still a generational divide among colleagues in evaluating what scholarship is most valuable.

Although the Broadening guidelines urge the inclusion of less traditional scholarship in the tenure process, the way in which departments value such scholarship remains uneven. Panelists agreed that there is still a generational divide among colleagues in evaluating what scholarship is most valuable, which creates challenges for incorporating the guidelines in departments. Hackel saw a consensus on recognizing untraditional scholarship dissolve when put into practice in evaluating untenured scholars doing nontraditional scholarship instead of, rather than in addition to, traditional publications. This divide allows senior scholars and more well-funded scholars to explore this new work, while junior scholars still feel required to produce traditional scholarship to advance in their careers.

Other sessions highlighted the diverse kinds of work historians are doing across the discipline today. At Historians Engaged in Public Policy, attendees heard from historians who have worked in the halls of Congress, for the Congressional Research Service, in a public relations firm, for the American Institute of Physics, and with the Department of Defense.

John Lawrence, a congressional staffer for 35 years, took a long view of how history and public policy have influenced each other. Across his career, he found that “one of the things you can do is integrate history into the work of the Congress,” something he said he thought was “one of the most satisfactory aspects of [his] career.” Ty Seidule (Hamilton Coll.) spent the majority of his career in the US Army as a member of the West Point faculty. He has been out of uniform for only the last five years, but most of his career was on the end of “executing policy, rather than making it.” Since his retirement, he has been able to be more honest, which he has applied to his diligent work in advocating for the removal of more than one thousand Confederate commemorations from military installations, from the names of forts and buildings to memorials.

Both William Thomas (American Institute of Physics, AIP) and Emily Blevins (Congressional Research Service, CRS) came to their current work because of their expertise in the history of science. Thomas, who is AIP’s director of research in history, policy, and culture, said that his role is new in the organization despite the existence of their history program for 60 years. This role allows him to work specifically on recognizing the diversity of the scientific community in the broadest sense, including examining disparities in science education between urban and rural communities. Blevins, on the other hand, began her nonacademic career at the National Science Foundation, where she was hired to write a book manuscript. She eventually worked her way up to the director’s office, where she contributed by writing speeches and op-eds. She then transitioned to the CRS, where, she said, “our main goal is to provide authoritative, nonpartisan research and analysis,” a unique position in the world of policymaking, since the researchers are not pursuing a particular outcome.

Now the vice president of a bipartisan public relations firm in Washington, DC, Mary Werden got her start in politics working for congressional races. She eventually became a communications director, managing the staff and candidate in a high-profile race. In 2016, she joined a congressional staff, then spent five years working in the personal office of the chair of the Energy and Commerce Committee. In this role, she assisted the legislative staff in talking about legislation and policy debates. During the pandemic, she said, “my job was to communicate to constituents not only how we could help them during a public health crisis but what we were doing in Washington.”

In these arenas, historians’ training gives them essential skills. As Seidule said, “History is storytelling with a purpose, using evidence. And that works everywhere.” Werden explained, “We know how to formulate arguments based on evidence, which you can do with any subject matter. And you can make it understandable to the less knowledgeable and the public.” Yet politicization can make this work difficult. Lawrence discussed how disagreements over basic facts—he pointed to the ways the events of January 6, 2021, have been manipulated and reshaped—make all policy work more difficult. And as Werden added, “We’ve entered an age of forgetting,” especially on issues like vaccines and infant mortality. But as Blevins argued, it can be important to think about why myths are persistent and why they are useful for those who repeat them. Rather than attacking myths head-on, she asks, “What small things around the edges can I tweak?” Such myths are “really good stories. So if you want to counter a myth, you need to think of a really good story that can go toe to toe.” Seidule’s position allows him to take an opposite stance. Since he is no longer in government, and never will be again, he can and will fight the Lost Cause mythology “until [his] last breath.”

Historians engaged with the US court system also find themselves working to correct the historical record. At How Historians Can Respond to the US Supreme Court’s Originalist Turn, chair Thomas Wolf (Brennan Center for Justice) and panelists Tomiko Brown-Nagin (Harvard Univ.), Jane Manners (Temple Univ.), Jack N. Rakove (Stanford Univ.), and Jennifer Tucker (Wesleyan Univ.) discussed historians’ case against the “originalist” interpretation of the Constitution that dominates much of our current legal landscape.

As Tucker said, “a lot of bad history” ends up in court cases today. The Brennan Center’s historians’ council has helped to organize amicus briefs and other legal work that can help to combat these ideas. Each panelist has contributed in different ways. Rakove, an expert on constitutional history and the founding of the United States, has focused on amicus briefs; he argued, “It’s our obligation as citizen-scholars to take this work upon ourselves.” Brown-Nagin said that she “brings to [her] work dual identities” as both a historian and a lawyer and law professor. She has learned through her focus on the Reconstruction amendments that “the conservative majority just doesn’t like the history so much.” Tucker, an expert on the history of guns in America, has cultivated a community of scholars interested in the Second Amendment in several venues, including a center for research on firearms, conferences, and even her course offerings, which are completely full, with long waitlists.

To Manners, this work goes beyond engaging with the judicial system. “Our discipline is facing a crisis. At the same time, there is a heightened interest in history from lawyers,” she said. “We should embrace this moment rather than shying away from it.” It’s a good reminder for historians in all fields that our work matters and, as Tucker said, it could be time to “seize the moment to apply some of our training to these questions.”

—LA and LM

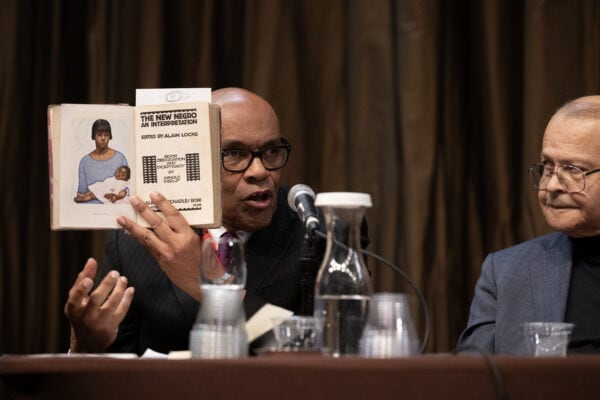

At the plenary commemorating the 100th anniversary of Alain Locke’s The New Negro, Jeffrey Stewart (Univ. of California, Santa Barbara) discusses the book.

Historical Detective Work

Meticulous historical detective work was the theme of the session The Digital Florentine Codex (DFC): An Illustrated, Multilingual Encyclopedia of Indigenous Knowledge from 16th-Century Mexico. Although the codex contains thousands of pages of text and images, the audience learned how even the smallest differences in the ways the authors slanted the text or how the artists represented speech scrolls reveal stunning new insights.

Kim Richter and Alicia Maria Houtrouw (Getty Research Inst.) introduced the Digital Florentine Codex project. An encyclopedia made up of 12 books, the codex recounts all aspects of life in 16th-century Mexico in both the Spanish and Nahuatl languages. Richter and Houtrouw explained how new text and audio translations from Spanish and Nahuatl were produced. The audio Nahuatl translations are significant, as this Indigenous language still has modern speakers but is endangered. Altogether, the DFC contains more than 200 audio files, 10,000 plain text files, 2,300 vocabulary entries in four languages, 15,000 multilingual terms and orthographies, and 25,000 image tags.

These image tags are particularly important, as previous printed editions of the codex reproduced only the text. But as Kevin Terraciano (Univ. of California, Los Angeles) argued, the images are crucial to understanding the text as a whole. Terraciano gave an example from his own research on the Nahuatl words teutul and teotl, and other words meaning “gods” or “word of god.” Before the DFC project, he said that it could take months, or even years, to comb through the entire codex and find the variations in spelling, meaning, and context for these words. But now that the codex has been digitized, much of this work could be condensed into hours and is more comprehensive, because researchers can connect the words directly to the illustrations.

Roxanne Valle (Univ. of California, Los Angeles), a first-year doctoral student, discussed the codex’s authorship. Spanish friar Bernardino de Sahagún is usually cited as the sole author of the codex, but many Nahua scholars contributed to these volumes. Some of these Indigenous contributors are known by name, but they remain largely uncredited in today’s scholarly literature. Valle and other scholars have used a three-step method to meticulously analyze each folio, uncovering variations in writing and illustration that revealed the distinct work of nine Indigenous writers and 21 Indigenous artists.

A large digital project such as the DFC provides many opportunities for classroom use. Lisa Sousa (Occidental Coll.) focused on possibilities for interdisciplinary collaboration. She has co-taught a course with the zoology department that used the codex as a primary text for learning about animals in Indigenous Mexico. She also has used the DFC in survey courses on colonial Latin America to build a digital pictorial manuscript about the conquest of Mexico. Sousa demonstrated how this project helped students think about how both historians and the authors of the codex created historical narratives. She also highlighted how this kind of digital humanities work can give students important skills for future careers.

Together, these presentations showed the breadth of research and teaching opportunities provided by the DFC. Seeing such a range of projects emerge from even very small parts of the vast codex left no doubt about the exciting opportunities for further research.

—LB

Busy Teachers, Big Continent

Across state academic standards for history, K–12 curriculum, and college world history classrooms, Africa is largely invisible. Egypt, the only part of the continent to receive regular and consistent coverage, is often associated with the Mediterranean or the Middle East. In State of the Field for Busy Teachers: Africa in World History, panelists faced a monumental question: How can we find room in world history classrooms for Africa, a place full of so many vast, rich, diverse, and vitally important histories?

Inspired simultaneously by both the needs of African nationalist movements who sought a “usable past” and the “persistent denial that Africa had a history before Europeans,” Jennifer Hart (Virginia Tech) said that historians have attempted to “write the history of Africa on its own terms” since African history emerged as a professional field of study in the 1950s. While African history is often disconnected from broader conversations in the discipline, there has been a “dynamic conversation” over the past generation of historians, notably within the World History Association, about how to move “the field of world history away from Eurocentric or Western-centric” histories. While the field has existed for over 70 years, the content is only now starting to filter into textbooks. Coverage of African topics is still “very incomplete and uneven.” The most successful attempts place Africa “at the center of global networks and processes and include African examples, like that of state formation, right alongside Europe and America.”

Hart and Sandra Greene (Cornell Univ.) explored new and exciting work on the histories of slavery and the slave trade as well as the history of development (a term that has economic, technological, scientific, and humanitarian dimensions). Research on these topics is doing “a lot of work to directly challenge conceptual assumptions,” Greene said, showing through comparative example that Western ideas of modernity and epistemology are not universal. Greene explained that there has been “tremendous work on where people came from and under what circumstances,” which have added the complexity of “African participation as partners” to histories of the African slave trade.

Food history is a way to instantly connect with students on Africa’s relevance in their daily lives.

When audience members asked how to better integrate African history into the curriculum, and how to defend its essential place there, the panelists encouraged the audience to build footholds in existing curriculum by simply making the presence of Africa more visible. Greene suggested using food history, particularly rice, as a way to instantly connect with students on Africa’s relevance in their daily lives. Relating regional struggles, such as water shortages, to students’ own experiences and environments could also help. Hart offered that “without African participation” in the production of gold, “European exploration would not have happened.” She also argued that classical Greek and Roman texts consistently document and acknowledge their own societies’ connections to the African continent. John Terry (Paideia School) pointed to religious history, saying that Africa is inextricably tied to the history of Christianity and noting Ethiopians’ influential involvement in the early church.

According to Hart, calls to “decolonize the curriculum” often stop with representation. But decolonizing the curriculum requires “conceptual work” and understanding more about “the way that our concepts are formed, where they come from, what baggage they’re carrying with them, and what they impose on others when we use them uncritically.” The panel prompted the audience to move away from framing Africa as a collection of political states, which encourages direct comparison with Western states, and instead engage with “small-scale societies,” some of which rejected state structure because it required “this massive hierarchy.”

These teachers admitted it is a “daunting task” to integrate Africa into world history, both on its own terms and in its importance in traditional Western histories, but the speakers urged consistent, relevant, and thoughtful coverage as a matter of human necessity. Hart said the exclusion of Africa from classroom content allows assumptions to thrive that “actively harm people on the continent,” as they “inform political conversations and policies and all sorts of other things.” Hart emphasized, “The evidence is on our side when we include these examples. Not including them is a political act.”

As a starting place, Greene encouraged teachers to first explore their interests on the continent: “Choose a topic you’re excited about, and it will grow from there.” Gesturing to the panel, Greene said, “We all pick different case studies and different exercises” in syllabi and classrooms,” but “skills development and historical awareness are the important parts.” Hart argued that teachers “can’t be an expert on everything” and to remember the goal is to get the students to “ask good historical questions” and help develop students’ understanding of context. As moderator Kyra Dezjot (Fordham Univ.) said in closing the session, “The first step is asking these questions yourself as educators.”

The session barely scratched the surface, but the conversation will continue at this summer’s NEH-funded Africa in World History Teacher Institute. With 15 faculty (including the State of the Field panelists) and 30 K–12 educators from around the country, the institute will culminate in the production of a free, digital sourcebook with accompanying lessons tailored to the needs of students in busy classrooms.

—WB

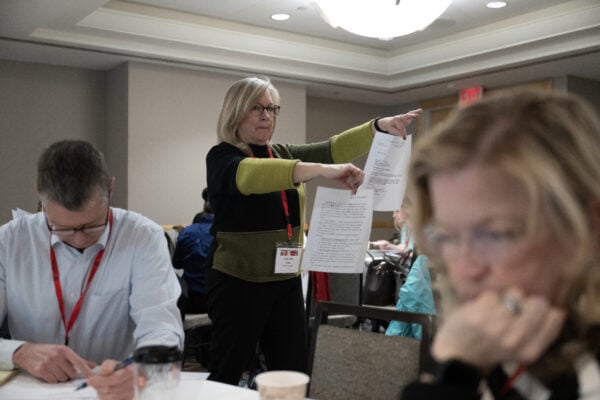

At the annual K–16 Workshop, Lee Ann Potter (Library of Congress) introduced participants to an array of primary sources ideal for classroom use.

The History MA Today

At The Worth of the History MA, three faculty members and one recent MA graduate convened to discuss “the place of the MA in university history education today.” Chaired by AHA Teaching Division vice president Kathleen M. Hilliard (Iowa State Univ.), the panel addressed the ways two institutions have tried to make their MA programs work for students.

Caitlin E. Murdock (California State Univ., Long Beach) led off the session by arguing, “We can sustain graduate education, but precisely because we should be emphasizing PhDs less and MAs more.” Those with history MAs “play a more direct role in interpreting history to the public”—as teachers, podcasters, museum professionals—“than those of us at universities do.” She posed three essential questions: What is the history MA for? What should the degree program require? And how do we recruit and sustain a diverse graduate student body?

Despite the MA degree often being seen as a stepping stone to a PhD program, the majority of MA students do not go on to complete a doctorate. Though there has been criticism of inconsistent career pathways, Murdock believes that this heterogeneity should be “a feature, not a bug.” Because of this, an MA degree should “give everyone a solid grounding in what we consider the essential skills” of a historian: historical thinking, historiography, content knowledge, and an ability to communicate. “We have a common project, whether you’re teaching, or at a museum, or a university,” Murdock said. “There is a common discipline, not just these separate silos.”

CSULB’s history MA program has therefore focused on making students of history into historians, and it has been fortunate in its enrollments. Its students include people from underserved backgrounds and nontraditional students, and it provides course schedules that are accessible for working people. This has required the department to institute “proactive, student-centered advising” and to work on creating community among its students.

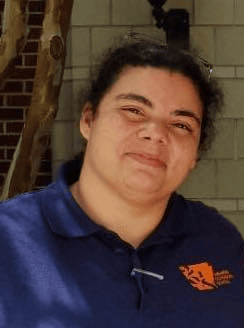

Both aspects were part of what made Victoria Gray’s (Los Angeles Unified School District) recent experience at CSULB so rewarding. A full-time high school teacher, she “was looking for ways to get more content knowledge,” and the CSULB MA track for teachers offers the same coursework but with a capstone option that includes lesson plans and student research. Participating in this MA program gave her “a cohort of like-minded teachers interested in advancing their content knowledge as historians.”

Eileen S. Luhr (CSULB) went into more depth about how the program fosters these communities. Early writing assignments help to identify which students may need additional help, and faculty can pair graduate writing tutors with MA students in their first semester. Such peer relationships “have proven to be really valuable” over the decade of this practice. Peer writing tutors help to position writing as “something we are all working on” and trying to improve. While teacher-students like Gray want to learn about pedagogy, their colleagues in the regular MA track are encouraged to take pedagogy courses too. “It allows students in the regular program to see their teacher peers as experts,” Luhr explained.

As director of an MA program at a PhD-granting institution, Leslie Waters (Univ. of Texas at El Paso) also finds that MAs often get overlooked compared to PhDs, not least because only the number of PhDs completed factors into a university’s Carnegie classification. She suggests making the MA program of study distinct from being an extension of or preparation for a PhD program. For students who may have transferred from a community college to BA institutions, they may have taken very few history courses. An MA can “serve to reinforce people’s interest in the subject matter for those who felt like they didn’t get what they wanted from the BA.” The MA program should offer different classes and assignments from PhD coursework—for example, not every class should end with a long historiographic paper assignment. Starting in fall 2025, UTEP has expanded options for a thesis, a comprehensive exam, or a public history project at the culminating experience of the program.

A robust Q&A session brought questions from audience members about how to expand their own institutions’ offerings. For faculty without K–12 teaching experience, how do they approach the pedagogy lessons? Luhr recommended that they be open with students that they might know more about K–12 teaching than the professor does, but she probably knows more about historiography. “If you are open to that, you can create something special.” Beyond the classroom, do these universities offer internships or other practical experiences? UTEP offers certificates in oral and public history, Waters explained, while Murdock said that they have an internship with The History Teacher journal, in addition to relationships built with local historical societies.

While much has changed in the discipline, higher education, and the world in the years since the AHA issued its landmark report on the MA degree 20 years ago, the questions from that study remain relevant. These institutions—and those represented in the audience—are thinking creatively to better equip MA students as historians, teachers, and citizens of the world.

—LA

Executive director James Grossman, who retires in July, was honored with a session about his career as a historian and AHA leader.

Mid-Career Opportunities and Challenges

Professional development for academic historians doesn’t stop after finishing graduate school or achieving tenure. Two sessions this year focused on mid-career historians, allowing them to reflect on their careers thus far and discuss how they see the challenges within the discipline.

Mid-Career Transitions was the second of four sessions in the Career Transitions discussion series, which invited attendees to reflect on “their own professional experiences and shared advice and insights on navigating pivotal career shifts.” Tony Frazier (Pennsylvania State Univ. and AHA Council) and Susan Gaunt Stearns (Univ. of Mississippi) facilitated the session, at which attendees discussed topics of concern for those both within and outside the professoriate.

Though organized for mid-career historians, attendees also included graduate students, early career professionals, and historians nearing retirement interested in learning about opportunities and challenges faced by their mid-career colleagues. Attendees did not define mid-career but agreed implicitly that it begins post-tenure for historians working in the professoriate, with a slightly more nebulous definition for historians working in other settings.

No matter the professional setting, however, attendees agreed that mid-career falls at the point at which historians have enough experience to step back and take stock, assess contentment, and clarify future goals. One attendee shared that she happily accepted a position as an assistant professor of history, but that the position had been a poor fit for her professionally and ill suited to her family’s needs. She is now actively searching for new employment either within or outside the professoriate. In her words, “Just because you got an academic job doesn’t mean you want to keep it.”

Mid-career is when historians have enough experience to step back and take stock, assess contentment, and clarify future goals.

Another assistant professor also shared that his mid-career reflections led him to search for new employment. He wanted a change in location, and his position included a heavy teaching and service load, leaving little time for research. He now teaches in a history department at a more research-focused university with a better balance of teaching, research, and service responsibilities.

The group discussed the need for historians in any job to continue to build diverse skill sets, both to secure promotions with current employers and to prepare for possible jumps to new jobs or career paths. Doing so, they noted, can require a significant expenditure of time on top of existing professional and personal obligations. Another attendee described how she applied for professional development opportunities in teaching and learning in higher education to learn more about settings where historians can engage with pedagogy outside the professoriate.

Ultimately, the conversation emphasized the importance of assessment at mid-career and some of the ways mid-career professionals can use their professional knowledge to, if needed, adjust course. One attendee noted, “Don’t let your education interfere with your thinking . . . you can do a whole host of things”—an important message for historians at any career stage.

Conversations about challenges at mid-career also played out in the session Marginalized Scholars at Mid-Career. As panelists noted, there is no one experience of a marginalized scholar. The history discipline has increasingly but unevenly diversified, and the structures that shape the tenure process, history pedagogy, support for research, and even faculty governance and accountability have been exposed as glaringly deficient in keeping up with the breadth of historians’ current work and labor. Jointly organized by the AHA Committees on LGBTQ Status in the Profession, Gender Equity, and Racial and Ethnic Equity, the session provided space for panelists to discuss the particular challenges of being a marginalized scholar at mid-career, beyond the more common early career focus.

Session chair Farina King (Univ. of Oklahoma) began by asking panelists to reflect on where the current generation of marginalized scholars maturing into mid-career (defined by the panel as just before, at, or after tenure review) experience particular challenges. Time and time again, student evaluations loomed large, frequently described as a space for a handful of students, protected by anonymity, to voice criticism that is implicitly or explicitly judgmental of professors’ identities. The panelists reported that students have criticized them outright for speaking too much about marginalized groups, particularly when the students project those marginalized identities onto the professor. Joshua L. Reid (Univ. of Washington), a registered member of the Snohomish Indian Nation who studies Native American history in the Pacific Northwest, quoted from one evaluation, “You just talk about Indians all the time.” As Ren Pepitone (New York Univ.) recounted of their first job at the University of Arkansas, students pushed back on reading “so many women” in a British survey course, of which Pepitone said, “Midway through the semester, we had only read two.” Dan Royles (Binghamton Univ., SUNY) said students accuse him of teaching “too much about civil rights,” or in one instance of being “too easy on gays.” But whereas the negative comments are memorable, panelists also spoke of students using course offerings to find community. Pepitone, who teaches “almost exclusively the history of gender and sexuality,” has students who “use my classes and my identity to find kindred spirits.”

The panelists demonstrated repeatedly that the modern academic historian has one foot in the archive and one in service of their institutional and local communities. Across the board, panelists are deeply engaged with community work but experiences varied in whether their institutions respected community work as professional work. Elizabeth Ellis (Princeton Univ.) recently became the history liaison for her own tribe, the Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma, and has found that “collaborative work really hard to quantify” by the most widely accepted rubrics for the tenure process. Royles said that at his previous institution, community-engaged work became hijacked by “perverse incentives” for a “hustle mentality” where professors were pushed to pursue specific projects to “work with minoritized communities” but the work itself “wasn’t necessarily helpful to those communities.” Pepitone said their department was having conversations about how to count public history work for tenure and promotion and a general uncertainty around how to do so. Reid pointed out, “If you have an institution or department that hasn’t figured out how to count it, most professional organizations have done so”—including the AHA. Erika Edwards (Univ. of Texas at El Paso) said her university has made great steps forward as an “open-access R1” and is “very much community engaged” and even offers a certificate “that allows professors to make their classes more community engaged.”

As their faculty have diversified, educational institutions have begun to see marginalized scholars as resources to utilize for service. From faculty governance to administrative positions overseeing diversity initiatives, grad programs to university commissions tasked with major reform, panelists reported feeling pulled in too many directions in early career—asked to take on too much, too quickly, and feeling unable to say no in their junior position. Reid encouraged that “no” can create space for someone else who needs to be present for hard conversations, rather than creating “bigger burdens on scholars of color” who “end up talking to each other” rather than the broader community. Edwards warned that institutions use younger faculty to do work for free that their predecessors were paid to do. Taking load-bearing positions within departments, as Royles did when he became graduate program director, revealed to him how gender dynamics in his department created more work, particularly for women, as older male colleagues unshouldered responsibility. Ellis, who ran an entire program pretenure, was unprepared for how many of her Indigenous students would ultimately turn to her when in crisis. Because the university lagged to provide sufficient support for vulnerable students, she faced a growing list of responsibilities to them, including making late-night calls for emergency housing. She also criticized institutions’ post–affirmative action shift to “trauma and perseverance” narratives as some sort of performance indicator for the academy, and how this translates to an “expectat[ion of] trauma from minoritized scholars.”

The historical discipline is evolving, and how it defines itself is expanding. While there is no longer any one typical way for an academic historian’s career to unfold, sessions like these reveal vital perspectives and strategies on how historians can continue doing good work and good history, wherever—and whenever—they are.

—WB and HS

Conversations abounded across the weekend’s three poster sessions.

America 250 Is Here. Are We Ready?

Across the United States, preparations are underway to commemorate the 250th anniversary of independence in 2026. Yet Americans remain deeply divided about the history and memory of the founding era. We’re all asking: What are the enduring legacies of the American Revolution? And is it possible to shift public debates about how we tell the story of the revolutionary era in more productive directions?

The Sunday-evening plenary wrestled with these questions during an event focused on the forthcoming documentary series The American Revolution, which will premiere on PBS in fall 2025. Filmmakers Ken Burns and Sarah Botstein joined screenwriter Geoffrey Ward and historical advisors Christopher L. Brown (Columbia Univ.), Kathleen DuVal (Univ. of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), and Alan Taylor (Univ. of Virginia) for a conversation about the many steps involved in creating the six-part film.

The session afforded attendees the first public sneak peek of clips from the new film, still in production. Its style and aesthetic fit within Burns’s iconic oeuvre—even the soundtrack echoes Jay Ungar’s “Ashokan Farewell,” a song now firmly associated with the Civil War in the minds of many Americans. Interviews offer insightful commentary interspersed between scenes that pair stock footage with dramatic voice-over narration.

The history presented on-screen grapples with some of the big questions surrounding the semiquincentennial, and the conversation onstage presented a welcome opportunity to learn more about the kinds of collaboration between filmmakers and historians that are creating a high-profile, new synthetic narrative of the revolution to engage the widest possible audience.

Burns and Botstein emphasized that this is a film, first and foremost, about the Revolutionary War, following the military campaigns across the continent. But, as the material screened at the conference made clear, its narrative engages with wider social, cultural, and intellectual implications of the political revolution that inspired the war in the first place.

The film is forthright about the frequent and brutal violence of this conflict.

A documentary film, of course, differs from other genres of historical narrative. Ward explained that, unlike books, film scripts do not use topic sentences, and the two directors offered insight into the challenges of crafting a visually stimulating documentary about a period before photography.

Careful historical research and writing informs every scene. One excerpt they screened, for instance, dwells on questions about what it meant for those who benefited from slavery to articulate universal ideals of freedom and equality, quoting from iconic documents penned by Phillis Wheatley Peters, Prince Hall, and others. Another clip—including commentary from DuVal—offered viewers glimpses of Native perspectives. In line with recent historiography, the film is forthright about the frequent and brutal violence of this conflict, so much so that Brown noted that he and other historians had even encouraged the directors to tone down some of the most excessive episodes.

Balancing careful history with compelling storytelling, this film, Burns and Botstein insist, seems poised to make an ambitious gamble that television audiences will welcome: an account of the revolution that embraces the complexity, contingency, and nuance of a period rife with contradictions. In thinking about an overarching thesis, Burns quoted a line from Wynton Marsalis in his earlier film Jazz (2001): “Sometimes a thing and the opposite of a thing are true at the same time.” The American Revolution, he explained, knocks down some of the more persistent myths of the era (think Betsy Ross and “the whites of their eyes”) while inviting audiences to ponder the messy ambiguities.

If the excerpts screened in New York (about 2 percent of the film’s total run time) provide any indication, the finished film will foreground some of the most innovative and accomplished scholars of the revolutionary era. “It’s going to be interesting to see what the reactions will be like,” noted Brown, a historian of slavery and abolition in the British Atlantic world. “We live in a bitterly polarized time, and this is a film about a bitterly polarized time. In that respect, it’s a film for our time.”

Polarized, yes, but perhaps not yet irredeemably so. The panelists agreed that there may be hope for the future. Botstein explained that she and her colleagues make films knowing that they will live on in elementary, middle, and high school classrooms, as well as a variety of other venues: colleges and universities, adult education, civic institutions, online, and in the reactions of audiences across the country and around the world.

In their concluding remarks, Botstein and Burns both emphasized their hope that historians—including the many different constituencies in attendance at AHA25—will have a role in shifting public discourse. “We want to work with you,” Botstein affirmed, “to make sure that as many people as possible can have a civilized conversation” about this often contentious history.

—BG

“You Have to Have a Vision”

Four well-known founders of major history museums in the United States gathered on the third morning of the conference to discuss “their motivations, challenges, and accomplishments in shaping institutions that preserve and narrate our collective past.” They included Ruth Abram, founder of the Tenement Museum; Lonnie Bunch, founding director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) and current secretary of the Smithsonian Institution; Alice Greenwald, founding president and CEO of the 9/11 Memorial and Museum; and Nick Mueller, founding president and CEO of the National World War II Museum. Annie Polland, president of the Tenement Museum, chaired the session.

The panelists began by sharing their museums’ origin stories. Abram explained that she wanted the Tenement Museum to both highlight immigrants’ experiences of living in New York City in the 19th and 20th centuries and demonstrate the important role stories about ordinary people can play in our collective understanding of the historical record. Nick Mueller shared that the creation of the World War II Museum actually stemmed from the founding of the D-Day museum, in which he was also involved. When they heard “You left out my part of the war” from veterans who did not take part in D-Day, they realized the need for another museum that could tell a broader story. Building the 9/11 Memorial and Museum, Alice Greenwald explained, began only five years after the events of September 11, 2001. It was “a time when families were still in the midst of intense grief. The city was traumatized. The war on terror was ongoing. Bin Laden hadn’t yet been found. That was the moment. No history was written yet.” Their job, they decided, “was to tell the story of this place.” And when describing the moment he was approached about taking charge of what would become the NMAAHC, Lonnie Bunch said he first turned them down, “because the idea of an African American museum on the mall goes back to 1915” and had never come to fruition. When he eventually agreed, he was hopeful that the millions of people who now visit the Smithsonian every year would flock to its newest addition. And so “why not,” he thought, “embrace the notion of expanding what America is by creating this museum?”

Lonnie Bunch (Smithsonian Inst.) shares his insights on the founding of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

In the years of work that followed those first moments, each grappled with the same questions: How did they define the museum’s mission and scope? Who did the museum serve? Where would they open the physical buildings? And how would they pay for it? Each panelist emphasized the central role that audience engagement played in defining their museum’s essential purpose. Abram wanted visitors to feel a deep emotional connection to the people whose stories they learned about at the Tenement Museum, and so its tours and storytelling focus on provoking an “emotional experience” in visitors. Mueller’s and Greenwald’s institutions needed to navigate a careful line between sharing truthful history with people who did not witness the historical events interpreted in their museums and holding space for remembrance, where eyewitnesses could share their stories, remember their own experience, and grieve for those they lost. And Bunch knew the NMAAHC would succeed only if visitors understood that “this story is for all of us, and [this story] profoundly shaped all Americans.’”

Those critical years between founding and opening brought numerous challenges. Bunch recalled searching far and wide for an engineering solution that would allow the NMAAHC to build lower levels into the earth without disturbing the groundwater, and with it the physical integrity of the terrain, which could impact the neighboring Washington Monument. The 9/11 Museum, too, faced issues with water—during construction, Hurricane Sandy flooded the museum with more than seven feet of water, damaging artifacts and causing months of delays. They also faced ideological challenges. Greenwald shared how “the tension inherent in museums of memory, which have to be both commemorative and documentary,” created issues. “Some families felt angry because they felt like the museum was usurping what was a battleground, a site of trauma,” she said. “One wrote an op-ed, and the next day [Governor] Pataki pulled the plug on the project.” It took five years of dogged work for Abram to secure the building where the Tenement Museum now resides; in the interim, they rented space and worked in a cramped and unheated basement. And Mueller recounted several instances when the World War II Museum ran out of money entirely, putting the project’s future in jeopardy.

Though they faced vastly different circumstances, each founder emphasized the centrality of struggle and failure, and the importance of remaining focused and resilient in the face of these challenges. Despite “going broke,” Mueller said, the World War II Museum’s “scale and size increased immensely over more than 30 years . . . because [of] shifting vision and learning over time and more people becoming interested and wanting some kind of involvement in the story.” Abram’s team eventually secured the building they needed for their museum site, and Greenwald’s pushed through political challenges and the devastation caused by the hurricane. Bunch said, “You start with a couple of staff, no money, and no collections. But what you have is a vision. You have to have a vision.” And that vision led to the NMAAHC’s opening in 2016, 100 years after the idea of opening an African American history museum on the mall was first floated.

Each founder stressed their belief that museums have a responsibility to help current and future generations better understand the world in which they live. Greenwald explained, “We knew at some point [the events of 9/11] would shift from memory to history. And it has . . . so the museum affirms the eyewitness generation and teaches the new generation so they can be literate about it in the world today.” Abram said the Tenement Museum’s focus on immigration aims to open the minds of their visitors to immigrants and refugees today. Mueller explained how the World War II Museum highlights the importance of protecting democracy at home and abroad. But Bunch perhaps described it best when he said the NMAAHC works to help “new generations . . . recognize that change is endemic to America and that it’s your responsibility to understand that history. The goal of a museum like ours is to make America better. . . . It’s about a museum that’s as much about today and tomorrow as it is about yesterday.”

—HS

A Chicago-themed puzzle at the AHA’s booth in the Exhibit Hall reminded attendees of where we’ll be next year.

On to Chicago

The 139th annual meeting will be held January 8–11, 2026, in Chicago. While the proposal deadline of February 15 will have passed before you read this, we hope that you will join us next year. Even if you haven’t proposed your own session, there will be many opportunities to participate—in workshops, drop-in sessions, and other events.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.