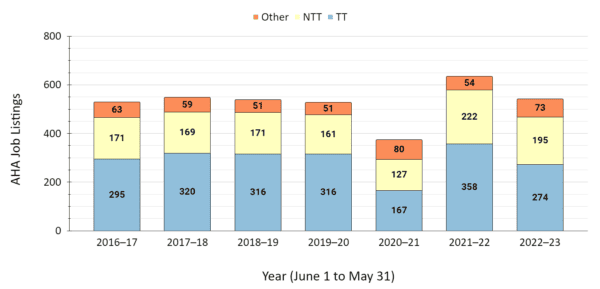

Last year, this report described academic hiring since the 2016–17 academic year as lethargic but stable. The notable exception—a sizable dip in job postings due to pandemic-related austerity measures in 2020–21—was seemingly balanced out by a relative increase in hiring in 2021–22.

Fig. 1: Job listings on the AHA Career Center by type and year from 2016–17 to 2022–23.

Data from the AHA Career Center for the 2022–23 academic year confirms this hypothesis. Overall, academic job availability in history has indeed returned to the steady but insufficient state of the late 2010s (Fig. 1). However, this general stability conceals two troubling patterns: (1) the rapidly declining number of jobs for premodern historians and (2) a decrease in the number of jobs that come with the possibility of tenure.

In total, there were 542 jobs listed on the AHA Career Center between June 1, 2022, and May 31, 2023. This number is well within the year-to-year variation (2016–22 median: 528, σ: 16) expected with stable hiring practices. However, the relative proportion of tenured and tenure-track (TT) jobs fell sharply, with 274 listed (2016–22 median: 316, σ: 24), making up just over half of all listed positions. Excepting the pandemic year (2020–21), this is the smallest number of TT jobs ever listed in a given year. By contrast, the number of listings for non-tenure-track (NTT) jobs grew to 195 (2016–22 median: 171, σ: 5). Excepting the postpandemic spike in 2021–22, this is the largest number of NTT jobs listed since 2016–17. Similarly, listings for jobs marked by the prospective employer as nonprofessorial increased to 73 (2016–22 median: 59, σ: 7).

Approximately 26 percent of TT listings were open rank (40) or sought to hire senior faculty (31). The AHA has not regularly tracked the number of listings for senior hires, so it is difficult to get a sense of whether or not this constitutes a change. Still, even relative consistency here—combined with a shrinking overall number of jobs—would mean that an increasing percentage of TT listings are unavailable to historians who have not yet found tenured employment.

In total, there were 542 jobs listed on the AHA Career Center between June 1, 2022, and May 31, 2023.

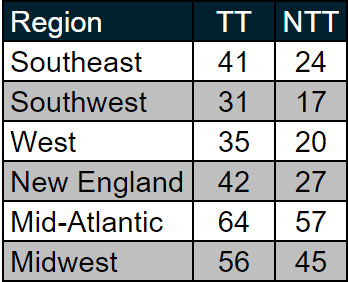

As might be expected, these jobs were not spread evenly across the country, with just under 40 percent (106 of 274) of TT jobs located in New England or the mid-Atlantic region (Fig. 2). Relative to their respective populations, Connecticut, Maine, Nebraska, Rhode Island, and Washington, DC, all saw a disproportionate number of jobs listed, while Alabama, Colorado, Georgia, Oklahoma, and Washington were underrepresented. No tenure or TT listings came from employers in five states: Alaska, Delaware, Mississippi, North Dakota, and South Dakota.

Fig. 2: Job listings on the AHA Career Center by US region, 2022–23.

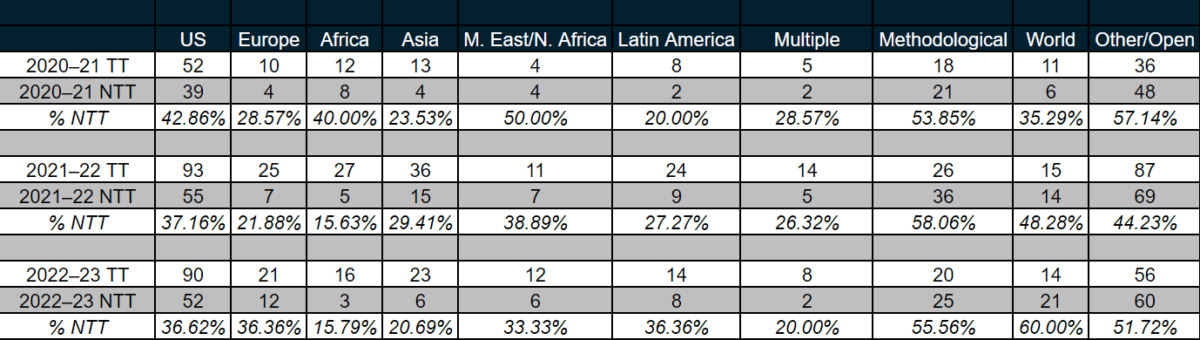

Similarly, academic jobs were not uniformly distributed across subfields and specializations (Fig. 3). Some areas were stable; others saw drastic decreases. Hiring in US history remained relatively consistent, with 90 TT jobs and 52 NTT jobs compared to 93 TT and 55 NTT jobs listed the previous year. Job listings for historians of Africa fell dramatically, with 16 TT and 3 NTT listings compared to 27 TT and 5 NTT listings the previous year. Similarly, listings for historians of Asia also saw a steep decline, with 23 TT and 6 NTT listings, down from 36 TT and 15 NTT listings in 2021–22. Because of the relatively small number of listings, it is too soon to tell if these changes are a normal year-to-year fluctuation or representative of a trend.

Fig. 3: Job listings on the AHA Career Center by subfield and tenure eligibility, 2020–23.

The growth of NTT positions at the expense of TT jobs affects some fields more than others. Over the past three years, only 22.5 percent of jobs in African history were NTT, compared with 30 percent of jobs in European history and 38.5 percent of jobs in US and Middle Eastern history. However, job listings defined primarily by a methodological rather than spatial category, listings in world history, and listings with no specification were more than 50 percent NTT.

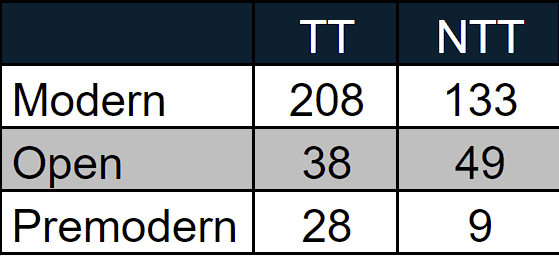

Perhaps the most notable statistic in the data from the 2022–23 academic year is the handful of listings seeking historians who specialize in periods prior to 1500 CE (Fig. 4). Of the 465 TT or NTT jobs listed, 341 (73 percent) specifically sought a modernist, 87 (19 percent) were open, and only 37 (8 percent) sought a premodernist. In short, jobs for modernists outnumber those for premodernists by a ratio of 10:1. This finding is in line with a recent follow-up to a 2021 report issued by the Medieval Academy of America (MAA), which found an average of 5 TT job listings for medieval historians each year over the past two years, down from a pre-COVID average of 11 to 13 jobs listed per year. Moreover, a disproportionate number of the AHA Career Center’s listings for premodernists (15 percent) were for senior hires only, further reducing the already tiny number of jobs available to junior scholars. As the MAA report warns, access to full-time faculty positions for premodernists is “a job lottery, not a job market.”

Fig. 4: Job listings on the AHA Career Center by general period, 2022–23.

In a system as complex as the modern US university, it is difficult—perhaps impossible—to identify the precise motive force or forces behind these shifts. But this data provides some hints. The shift toward NTT positions probably derives from a combination of tightened institutional budgets and a desire among university administrators for increased flexibility. This hypothesis is supported by widespread (if anecdotal) testimony from many departments that are finding it increasingly difficult to secure new tenure lines, as well as the higher rates of NTT positions in what have traditionally been bread-and-butter subjects (e.g., US and European history). Similarly, open or methodological listings may be intended to offer students variety. Given that most history programs are experiencing decreasing or static enrollments, the desire to hire where students want to learn is understandable.

The desire to hire where students want to learn is understandable.

If there is indeed a movement toward hiring purely with teaching classes in mind, that tendency would also explain the relative (and absolute) dearth of jobs for premodernists. The utility of the study of history—like other humanities and social science disciplines—continues to receive intense (if poorly informed) scrutiny, and that scrutiny is several orders of magnitude greater for subfields and subjects not immediately connected to current events in the United States—or at least, not in the minds of many legislators, administrators, and students. This perception must change.

It has, after all, been 25 years since academic Cassandras warned that historians must persuade those outside the discipline of the importance of historical subfields not obviously linked to current events. As Kathleen Biddick put it, “Unless scholars try to redescribe their discipline outside its 19th-century parameters, it will die out in the curriculum.” That warning was timely when it was first made; it is even more important to heed now.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.