In the words of one recent history PhD who is currently employed part time, the employment situation can be summed up quite simply: “No jobs, no money, no status, no hope.” This sense of growing despair about poor work conditions, absent collegiality, and the possibility of being relegated to a permanent underclass in the profession pervades the responses to a recent survey of part-time and adjunct history faculty.

The survey, designed by the Joint AHA-OAH Committee on Part-time and Adjunct Employment, and distributed through the newsletters of the two organizations, received 276 responses, with 256 responses from historians currently employed either as adjuncts or part-timers. While this only represents a tiny portion of the almost 11,000 historians employed part time, the survey found important points of convergence with an earlier survey by the Department of Education, while filling in additional details.1

Members were asked to fill out a multiple-choice questionnaire with some additional opportunities for comments, but many respondents added comments throughout the form, making data interpretation rather difficult, as there are so many levels of part-time employment.

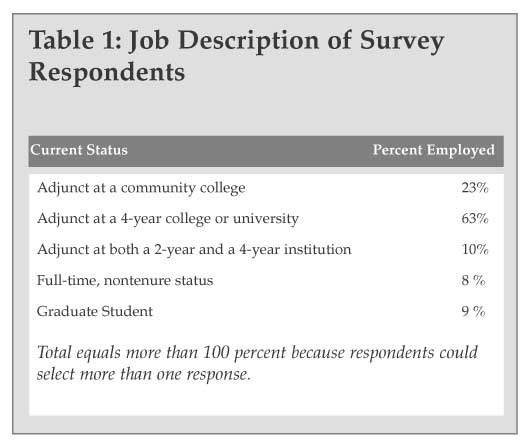

The demographics of the responding faculty members were quite similar to a less-comprehensive survey conducted by the AHA three years ago.2 The respondents represented a wide range of employment contexts (Table 1) and experiences, and were employed in more than 40 states and the District of Columbia (three of those surveyed were employed in Canada and France). The respondents also had varying levels of academic achievement: just under two-thirds had completed a PhD, while 21 percent held a Master’s degree, 4 percent were doctoral students, and 12 percent had the ABD status.

The demographics of the responding faculty members were quite similar to a less-comprehensive survey conducted by the AHA three years ago.2 The respondents represented a wide range of employment contexts (Table 1) and experiences, and were employed in more than 40 states and the District of Columbia (three of those surveyed were employed in Canada and France). The respondents also had varying levels of academic achievement: just under two-thirds had completed a PhD, while 21 percent held a Master’s degree, 4 percent were doctoral students, and 12 percent had the ABD status.

Given the large contingent of respondents who are at a fairly early stage in their career, it is not surprising that most of the respondents had been employed as adjuncts for less than 5 years. However, an almost equal number had been teaching in that capacity for more than 6 years, with respondents holding a PhD the most likely to be in this category. The great majority of those surveyed (68 percent) had never been employed in a full-time capacity.

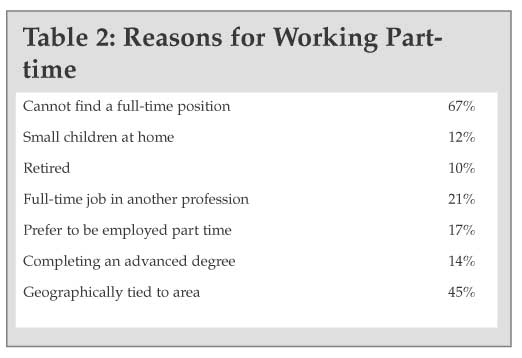

The respondents offered a multiplicity of reasons for working part time (as indicated in Table 2). The largest, and perhaps most obvious, was an inability to find a full-time position. However, the responses also highlighted the factors that constrained their choices, and often prevented well-qualified history PhDs from making an extensive job search. Almost half of those surveyed cited ties to a particular locality or region-typically related to the needs of family, or the employment of a spouse or partner.

The respondents offered a multiplicity of reasons for working part time (as indicated in Table 2). The largest, and perhaps most obvious, was an inability to find a full-time position. However, the responses also highlighted the factors that constrained their choices, and often prevented well-qualified history PhDs from making an extensive job search. Almost half of those surveyed cited ties to a particular locality or region-typically related to the needs of family, or the employment of a spouse or partner.

Beyond these factors however, a large number of respondents suggested in their open comments that age discrimination contributed to their underemployment. The ages they marked as subject to such discrimination ranged from 40 to the mid-50s. Although just under 12 percent of the respondents (29 out of 256) expressed this concern, none of the survey respondents had made the point in the survey conducted just three years earlier. This was the most noteworthy change since that survey. A number of commentators expressed surprise at some departments’ apparent refusal to hire PhDs who received their degree later in life. As one noted, “I had not anticipated this level of age discrimination, which is remarkably shortsighted. To keep expenses down, the profession should hire older folks: we retire sooner and therefore top out at lower salaries. Turnover works to keep costs down.”

Indeed, this concern seemingly displaced perceptions about race and gender discrimination that were prevalent in the earlier survey. Nevertheless, the latter concerns were still present in a few of the comments. As one part-timer observed, “the bottom line is that the profession discriminates based on age, race, and gender, as well as previous military status. If we believed in an equal and fair hiring process, these should not be a factor.”

Asked where they would accept employment, most respondents wanted full-time employment at a four-year college or university, though these expectations seemed to diminish the longer they had been on the job market. All of the doctoral students still had their sights set on 4-year institutions, while less than 88 percent of those with PhDs and only half of those who had been on the market for more than six years expressed this goal.

At the same time, the current surfeit of history PhDs on the job market frustrates the aspirations of a number of job applicants, particularly those who had not completed the PhD. This arises, in part, from unrealistic expectations about their employment options. Around 75 percent of the respondents working with Master’s degrees, for instance, said they would not take a full-time position at a public or private high school, but would take a position at a 4-year institution. As we have noted in previous surveys of the academic job market, in the past decade very few historians have been hired at 4-year colleges and universities without a PhD in hand or imminent.3 A number of those surveyed remarked on this problem. One respondent noted, “ABD status is a hindrance, even for community college positions.”

Often the part-time jobs are taken out of sheer necessity. A number of graduate students and ABDs noted the hard choices they face, particularly balancing the need to teach in order to meet expenses against time taken away from completing a dissertation. One adjunct complained, “The biggest obstacle [I face] is feeling used and not having money for conferences, research. . . . And groceries!”

Regardless of their degree status, a number of the respondents complained of being relegated to “second-class status”, attributing this to academic elitism. One part-timer reported that, “once you [have] become an adjunct, you are ‘damaged goods’-no one wants [to hire] the profession’s leftovers.”

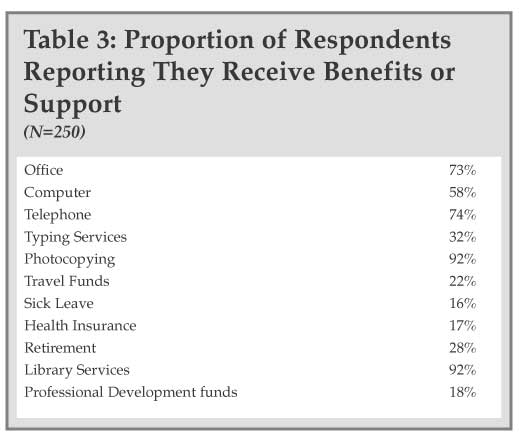

The respondents reported significantly less in the way of employment benefits and support for their scholarly work (see Table 3). Less than 20 percent had access to health insurance, sick leave, or professional development funds at any of the colleges or universities that employed them.

The respondents reported significantly less in the way of employment benefits and support for their scholarly work (see Table 3). Less than 20 percent had access to health insurance, sick leave, or professional development funds at any of the colleges or universities that employed them.

Lack of health insurance and retirement plans were major issues irrespective of the age or length of career of the respondent. The constant worry about coverage for medical costs had a draining effect on careers. Many explained that as they search for time and funding to finish their degrees, they remain graduate teaching assistants in order to keep student health insurance. Others said they were grateful for spousal/partner insurance policies.

Some respondents hoped that the AHA or another academic association would push for the opportunity for adjuncts and part-timers to contribute to a TIAA-CREF retirement plan. Others expressed hope that their institutions would start providing retirement packages. Because the history profession has more members in the oldest demographic cohort than other academic professions, retirement plans are becoming more and more essential, especially for those who put together a piecemeal living.4 This lack of stability, coupled with the lack of financial security, caused one respondent to remark on a “sense of failure and uncertainty about the future.”

The responses also highlight the wide array of work arrangements that often have to be cobbled together to earn a living as a part-time employee. While a large majority of the respondents were employed at a single college or university, over 30 percent of the respondents were employed by two or more schools. And 29 of those still employed as adjuncts (11 percent) reported that they were doing some web-based distance learning. Although the question was never explicitly asked, a number of those surveyed spoke of other jobs they’d taken to maintain a basic standard of living.

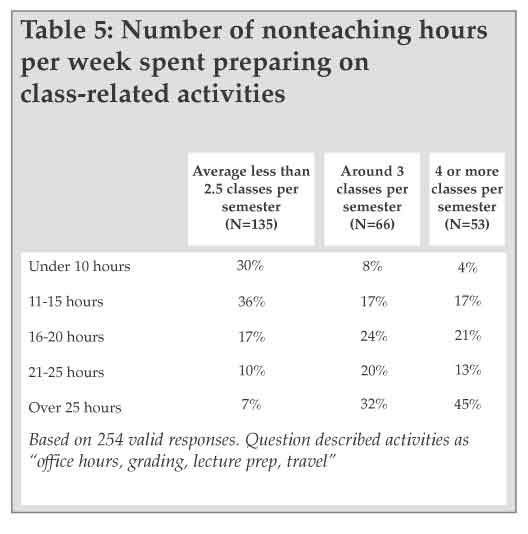

Despite such competing pressures, the adjunct faculty who responded to the survey taught an average of almost 3 classes each semester. In addition to the time spent in the classroom, 54 percent of the respondents reported that they spent more than 16 hours a week on class-related work, such as office hours, grading, preparing lectures, and traveling to school (Table 5).

Unfortunately, the data on salaries was a bit more muddled. The average reported payment per course was in line with that reported by departments in our other surveys, averaging $2,855 per class (among the 162 who were paid this way and gave a valid response). However, the data from those paid by the credit hour was impossible to calculate, because a large number responded with the amount per hour of classroom instruction and a number of others indicated that they were paid by the student.

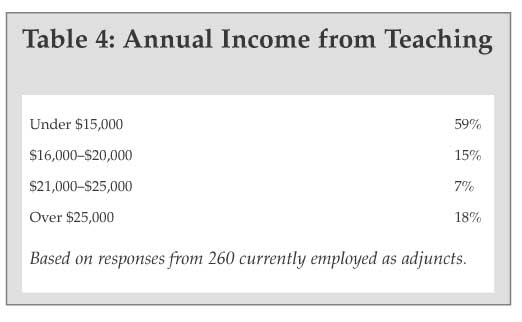

Regardless of the payment per class, almost 60 percent of those surveyed said they earn less than $15,000 a year from teaching (Table 4). More than 64 percent of the respondents reported that they rely on the added income of a spouse or partner to make ends meet, and 41 percent of the respondents also needed additional income from jobs outside of higher education.

Regardless of the payment per class, almost 60 percent of those surveyed said they earn less than $15,000 a year from teaching (Table 4). More than 64 percent of the respondents reported that they rely on the added income of a spouse or partner to make ends meet, and 41 percent of the respondents also needed additional income from jobs outside of higher education.

Increase of pay, even for the better-paid adjuncts, is still the biggest demand. Adjuncts appealed for equal pay for equal work, stating, “it is very degrading to work so hard and to [only] be paid 50 percent of what the full-timer gets for teaching the same course.” Many requested that they be compensated for non-teaching departmental or university responsibilities, such as committee work, which is currently factored into tenure-track faculty pay but not for part-time instructors.

The institutional support for their work was in line with their compensation. Only 73 percent of the respondents had a shared office or telephone on campus to interact with students (and such respondents tended to have these resources at some but not at all of the schools where they are employed). Barely half had access to a computer in the department. Most explained how they must share an office or desk, having no place to put students’ records, let alone the ability to meet privately with students.

In addition to stressing the basic lack of economic support, a significant number of respondents complained about the lack of basic collegiality from other faculty and administrators in the department. They saw the absence of financial support as being of a piece with their treatment by faculty “colleagues.” As one respondent noted, “being ignored by the dept and the university is one of the hardest difficulties. I feel like a robot. Robots don’t require retirement and insurance.” And a couple of the respondents observed that their students had noticed this treatment by the university. One respondent noted the difficulty of “facing students who know that education isn’t very important since colleges use so many adjuncts.”

In addition to stressing the basic lack of economic support, a significant number of respondents complained about the lack of basic collegiality from other faculty and administrators in the department. They saw the absence of financial support as being of a piece with their treatment by faculty “colleagues.” As one respondent noted, “being ignored by the dept and the university is one of the hardest difficulties. I feel like a robot. Robots don’t require retirement and insurance.” And a couple of the respondents observed that their students had noticed this treatment by the university. One respondent noted the difficulty of “facing students who know that education isn’t very important since colleges use so many adjuncts.”

Despite being disappointed with their current employment, and often bitterly angry with the profession, a slight majority (53 percent) said they were still inclined to continue in adjunct positions rather than leave the profession. Nevertheless, almost a third of the respondents have reached or surpassed the point at which they intend to seek full-time employment in another field. As one respondent declared, “I made a career switch. I am now a gentleman historian.”

Several respondents offered suggestions on how to deal with the issue of overuse of part-timers, ranging from permanent part-time positions with pro-rated full-time benefits and wages, to the creation of a promotional system that would allow adjuncts to move onto the tenure track.

The respondents also had a number of pointed comments for the professional associations and the profession as a whole, demanding that the AHA take a stronger stance on the behalf of part-timers, and asking all faculty to remind administrators that educational excellence and a diverse faculty, which includes part-timers as equal members of a department, should not be incompatible goals for the profession. As one adjunct commented, “part-timers are not second-class academics. With proper and fair access and recognition, [they] can publish, receive grants, do vital innovative research, and create challenging and rewarding educational opportunities for students.”

Notes

- See Robert B. Townsend, “New Data Reveals a Homogeneous but Changing History Profession,” Perspectives (January 2002), 7. [↩]

- Robert B. Townsend, “Part-Time Teachers: The AHA Survey,” Perspectives (April 2000), p. 7. While the earlier survey, conducted in fall 1999, was distributed more widely through the H-Net lists, the survey instrument was shorter and more open to responses from those who were longer employed as adjuncts. As a result, the number of responses from those employed in a part-time or adjunct capacity was only slightly smaller (260 in this survey, as compared to 380 in the last). [↩]

- Robert B. Townsend, “Job Market Report 2001: Openings Booming . . . but for How Long?,” Perspectives (December 2001), p. 7. [↩]

- Townsend, “Homogeneous but Changing History Profession,” 7. [↩]