“Akulanga lashona lingenazindab” is an isiZulu phrase meaning, “No day goes without its stories.” Stories of individual experience are central to my history courses on South African and world history. But when my spring 2020 undergraduate course on the history of South Africa shifted online due to COVID-19, I reevaluated my assignments and overall pedagogy. I quickly realized that, in an online environment, research papers failed to have the desired impact of reinforcing historical techniques and research skills. Instead, I moved away from the traditional research paper and embraced archival analysis assignments where students presented their research on archives and online databases from South Africa and the United States.

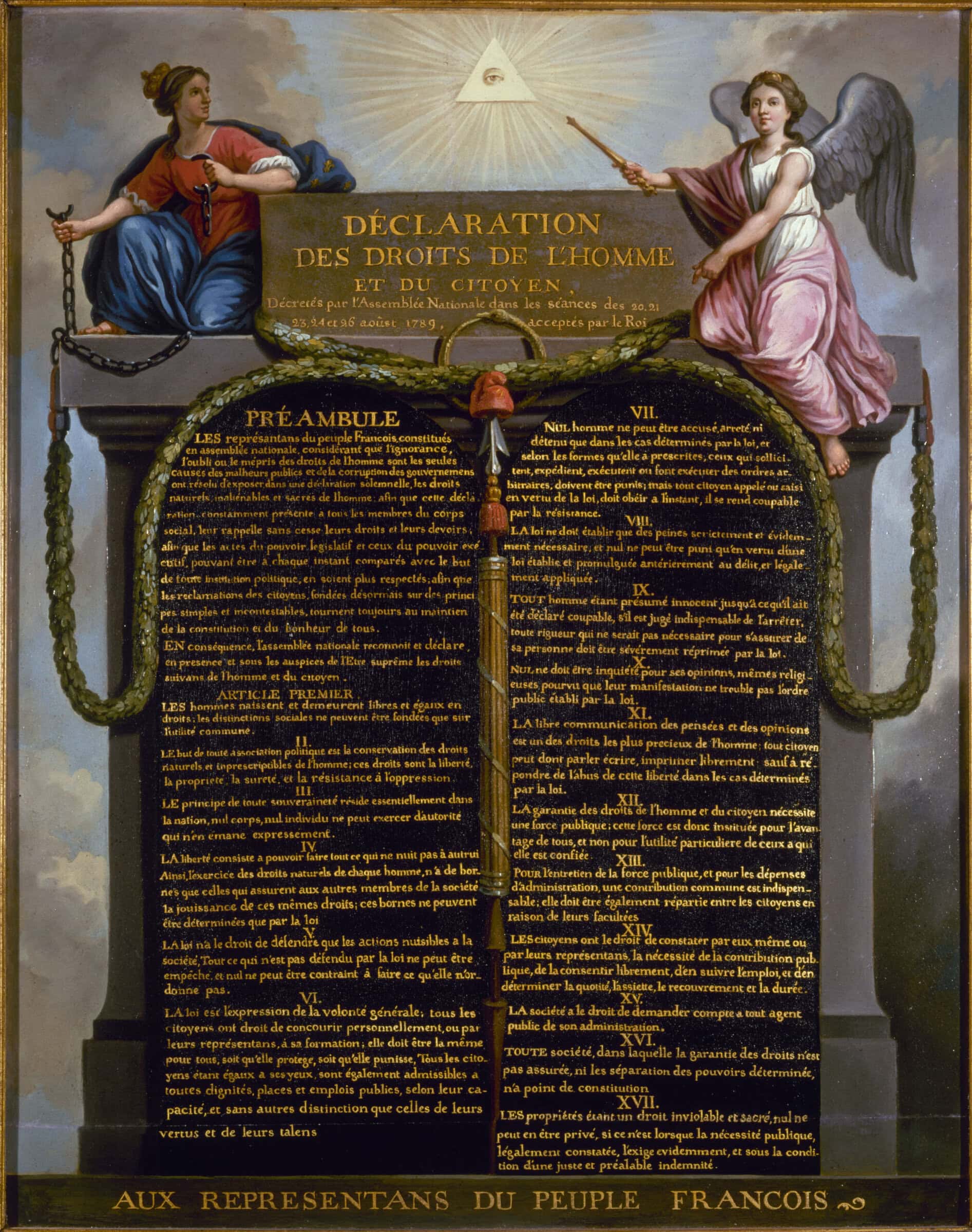

In the “Land Act Legacy: 1913 to 2013” assignment, Jacob Ivey‘s students used digitized sources and oral interviews to do guided research projects. Chicago Anti-Apartheid Movement collection, College Archives & Special Collections, Columbia College Chicago. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Using previous digital humanities projects as a model, I instead created an assignment entitled “Land Act Legacy: 1913 to 2013.” Students researched and prepared short presentations on the 1913 Land Act’s legacy of economic and political disenfranchisement. To reveal the diversity of Africans impacted by this unjust law, I walked students through the personal narratives from the South African History Archive’s (SAHA) “The Land Act Legacy Project Collection,” an online depository of oral history materials and photographs collected for the centennial of the 1913 Land Act, one of the key pieces of legislation that established the foundations of the system of apartheid.

Stories of individual experience are central to my history courses on South African and world history.

Taking the research skills and practical knowledge acquired during the first half of the semester, students began scouring the SAHA for oral interviews from those who experienced land removal in 1913 and its aftermath. From there, each student focused on one individual and the geographic areas they or their family was removed from, investigating how removal had an impact on individual lives and the landscape of South Africa. Many of these interviews are with people born after 1913, but they provided insight into the underlying impact of apartheid. In some instances, students discovered interviewees’ family members who are active in the Economic Freedom Fighters’ “Land Expropriation Without Compensation” campaign today in South Africa. Unlike a research paper, which could be overwhelming or unwieldy for many undergraduates, particularly nonmajors, delving into a single, well-managed archive provided students with a focused set of research materials that helped to build a foundational point of historical inquiry. Instead of teaching them to write like a historian, they learned to engage with the tools and mechanics of historical research. Students still “thought like historians” by looking at causality, context, complexity, and more. But with the entire class focusing on one event, the 1913 Natives Land Act, students could concentrate on the impact on the lives of everyday South Africans and its resonance in present-day South Africa.

Students responded well to this guided research project. Notably, they were able to overcome the initial hurdles of research, including identifying a topic early in the semester, finding and accessing the validity of certain archives, and writing without hands-on support. With the SAHA’s resources in hand, students had the time to deconstruct sources and material while developing a deeper insight into the people and places impacted by the racist apartheid policies in 20th-century South Africa. While some students expressed reservations about a project on “land,” they soon realized that land policy remains a heated issue within South Africa and one of the clearest avenues to understanding the legacy of imperial influence in the postcolonial world.

We are not stagnant because we are online.

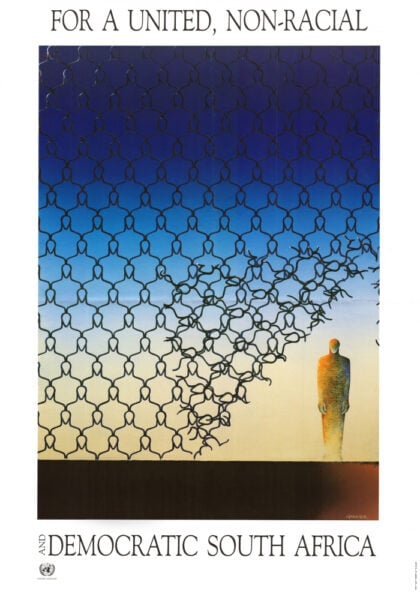

Inspired by the success of this project, I created a similar assignment for an upcoming course on the global Black diaspora drawing on the African Activist Archive. I explain at the outset of this project that I use these sources in my own research examining the anti-apartheid movements in Central Florida, highlighting these digital tools’ usefulness in the classroom and broader research on the history of the African diaspora. Using this database of documents and ephemera, students dig into one aspect of activism in the United States that supported South African struggles against apartheid from the 1950s through the 1990s. The year 2020 has taught us that protest movements are essential components in understanding the importance of civil disobedience during times of political and cultural change. By engaging with the stories in these digital archives, students learn about the diversity of opinions and opportunities that defined eras of global protest, making transnational connections between Black intellectual life and late 20th- and early 21st-century politics and revolutions.

As I continue to teach online in spring 2021, I am comforted to know that my pedagogy can and will continue to be influenced by the resources and scholarship that emerge within the fields of South African history. Future projects will emphasize the wealth of online material available to students, from the Struggles for Freedom: Southern Africa archive to the Forward to Freedom archive to the South Africa: Overcoming Apartheid, Building Democracy collection. From these sources, students learning and researching from home can continue to engage with the unique and compelling story of South Africa as revealed by vital archival collections.

We are not stagnant because we are online. “Akulanga lashona lingenazindab” holds true whether those stories are shaped in a face-to-face or remote classroom. The stories have not changed, just the way we teach them.

Jacob Ivey is assistant professor of history at Florida Institute of Technology. He tweets @IveyHistorian.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.