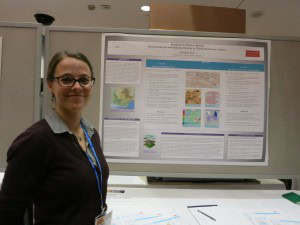

The winner of the 2015 annual meeting conference poster contest is , who will receive free registration for the 2016 meeting in Atlanta. Axen is in the History Department at Boston University completing a dissertation on the religious landscape of medieval southern France, entitled “Mapping the Bishop of Avignon: Sources of Episcopal Power in the Thirteenth Century.” Here, Axen reflects on the experience of presenting her research in the poster format at AHA 2015.

In the professional setting, historians rarely get the chance to toy with color schemes or accost passersby with their thesis statements and esoteric evidence. At the poster sessions, the double rows of posters facilitated a constant flow of conversation between presenters and historians milling on the mezzanine of the Hilton Midtown. Over the course of the session’s two and a half hours, I received feedback from medievalists, digital mappers, and historians of religion who offered new insights into the particular angle of my project that most resonated with them, as well as from intrigued scholars whose work was completely unrelated to my own. Each person who considered my poster was able to hone in on the part that unlocked his or her interests. As a result, my conversations ran the gamut from precise commentary on the mapping software I used, to debate about recent methodological shifts in the study of religious experience, to the roles of women in medieval hospitals and convents. This versatility is the strength of poster sessions. Because traditional AHA panels consist of experts speaking to a largely passive audience, the posters filled a need for dynamic, informal conversation guided only by genuine interest and the pleasure that comes from finding someone else equally passionate about your little corner of the past.

The conference poster format encouraged us to rethink the important “big picture” questions that frame our work by forcing us to condense our projects into five-minute slices. My poster featured case studies from two chapters of my dissertation, and by deciding which data to include and how to arrange them, I perceived certain connections that had not been obvious from writing about the material. Transforming written evidence into a visual format provided me with a new chance to arrange, categorize, and zoom in and out of my argument so that I could clarify and finesse the material. It enabled me to get to the heart of the adage, “show, don’t tell.” In giving the audience the necessary pieces of the argument in a flexible display, comprehensible from top-to-bottom and side-to-side, the poster granted a taste of the project. Viewers could then draw the conversation in any direction to talk about topics that were sparked by the poster but not necessarily recorded on it. The incorporation of poster sessions as a significant platform for new work, as it is in scientific disciplines, will make history conferences increasingly accessible, creative, and rooted in personal contact.

The session left me gratified and confident that my work is broadly interesting and relatable—a concept that can be difficult to remember in the isolating process of dissertation writing. I am very thankful to the dozens of scholars who stopped at my poster to share their own work, recommend pertinent books, and offer constructive criticism of the project and formatting. I encourage conference posters to be taken seriously as opportunities for sowing the seeds of a project among a wide, expert audience, for engaging with senior scholars in our fields, and for trying out arguments that may still seem immature—in all of these cases, the most valuable benefit was the focused discourse with colleagues with whom we otherwise might not have conversed. The rewards are immediate: some of the scholars I met at my poster have already suggested collaborating on future conference panels, and I look forward to keeping abreast of their projects, too.

By way of advice for next year’s conference poster presenters, I found it useful to provide 8.5×11″ printouts of my poster so interested parties can remember my work at a glance. I also recommend placing summarizing statements at the beginning and end of the poster, so that people approaching from left or right can quickly understand the pith of the project. Finally, I encourage future poster presenters to pursue artistic, appealing, colorful displays that will catch an eye from across a crowded room.

The deadline for poster proposals for AHA 2016 in Atlanta is February 15, so check out our Submitting a Proposal page to learn the details.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.