In February 1942, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which directed state and local authorities to locate and detain Japanese American citizens and their family members in the western United States at a number of prison sites. In addition to being given only days to prepare for their imprisonment, Japanese Americans received little information about their destinations, the proposed length of their stay, or the conditions they would endure. They were told to pack what they could carry and then were abruptly forced from their homes. Of the roughly 120,000 people who were subjected to this treatment (primarily in California, Oregon, Arizona, and Washington), most spent the next three years in prison.

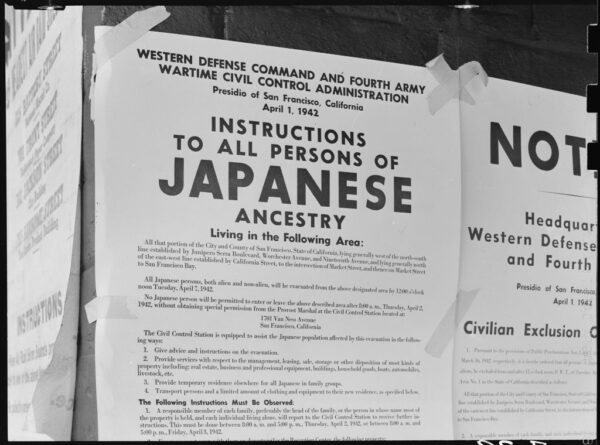

An Exclusion Order commanding the removal of Japanese Americans from a section of San Francisco. Wikimedia Commons

Before being formally incarcerated, Japanese Americans were first detained in one of 17 so-called “assembly centers.” The bulk of these were located in California, with three other sites in Oregon, Arizona, and Washington. The majority of these temporary jails were makeshift arrangements, such as former fairgrounds and horse tracks. Following this interim period, inmates eventually arrived at prisons where they would stay long term. Called relocation centers in most official correspondence (but also internment camps and, on occasion, concentration camps), these prisons were created and administered by the War Relocation Authority. A total of 10 such prisons existed: Gila River and Poston in Arizona; Granada in Colorado; Heart Mountain in Wyoming; Jerome and Rohwer in Arkansas; Manzanar and Tule Lake in California; Topaz in Utah; and Minidoka in Idaho.

On January 30, we celebrated the legacy of civil rights hero Fred Korematsu, who was one of three Japanese Americans to challenge the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066 before the Supreme Court. February 19 will mark the 75th anniversary of Roosevelt signing the order. Even as we acknowledge these historical milestones, we face the horrific realization that the same dangerous impulses and rhetoric that led to the mass imprisonment of over 100,000 innocent citizens and their family members once again lie at the heart of President Donald J. Trump’s recent executive orders regarding immigration. In this critical moment, history has especially important lessons to teach us about racism, religious prejudice, and the importance of basic human rights.

Much attention has rightly been paid to the legal and economic harm that institutionalized bigotry can cause, as well as to the various factors that feed that bigotry. Even as we bear these important matters in mind as teachers and as members of civil society, we might consider lifting our eyes for a moment from this sadly familiar historical terrain, direct them toward the horizon, and consider the most elusive, but also perhaps most important, challenge before us. In response to discourses of fear and withdrawal from the world, we must strive for a more measured, historically informed, and above all empathic engagement with the world.

Take, for instance, the fallout of wartime incarceration specifically in the United States. (Canada, too, undertook to remove all people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast.) At high schools and universities from California to Washington, Japanese American students were summarily expelled, despite having never even been arrested or charged with any crime. Families lost their homes, their businesses; entire communities were uprooted and dispersed inland. Life in prison only added insult to these various preliminary injuries. In both the short-term way stations and longer-term prisons, inmates endured repeated violations of their civil and human rights, as well as a host of related indignities—all the while being surveyed for possible inclusion in the American war effort. (In February 1943, inmates were subjected to what became known as the Loyalty Questionnaire, an ancestor of “extreme vetting” that comprised approximately 30 questions designed to assess the suitability of Japanese Americans for placement outside prisons and, in case of eligible males, military service.) Life under these conditions left inmates in a constant state of distress and uncertainty about their safety and future, particularly given the clear link between wartime incarceration and the years of anti-Asian prejudice that preceded it. Indeed, there is evidence, both contemporary and observed at the time, that distress and uncertainty never fully subsided, and that many families continue to suffer the aftereffects of unjust incarceration based on racial and religious prejudice.

As we witness the government of this country lurch from reactionary move to reactionary move, we would do well to reflect on not only large-scale events and topics, but also other sorts of cultural work, such as that which the Japanese American community has tended to pursue in the wake of wartime injustice. From congressional testimony in support of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which granted reparations to Japanese Americans who had been imprisoned, to participating in retroactive diploma ceremonies all along the West Coast, these people have sought to demonstrate much more than the fact that the past is repeatable, and that such repetitions are avoidable. They also have sought to demonstrate to others that action derives first and foremost from direct, emotional investment in human rights and civil liberties. This is what Fred Korematsu had in mind when he spoke and wrote against religious and racial profiling after 9/11: “I know what it is like to be at the other end of such scapegoating and how difficult it is to clear one’s name after unjustified suspicions are endorsed as fact by the government.”

Injustice, whether proposed casually or pursued programmatically, exacts a toll that is personal as much as anything else, and its corrosive effects work at an individual level. But they affect not only the target of unjust behavior and vicious sentiment; they also affect those who trade in such behavior and voice such sentiment. The people who peddle stereotypes seek to perpetuate convenient abstractions drained of all emotion, save fear, which drives us away from one another and into increasing isolation. Empathy, by contrast, draws us together. It is the force that can bind us to one another personally and, in so doing, help us to move beyond dry templates for thought and toward genuinely productive action. Informed by a rigorous understanding of the past, it may be our most powerful tool for navigating the challenges of both the present and the future.

’s new book, The Long Afterlife of Nikkei Wartime Incarceration (Stanford Univ. Press, 2016), maps the intergenerational, cross-cultural, and cross-racial consequences of suspending rights in the name of national security.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.