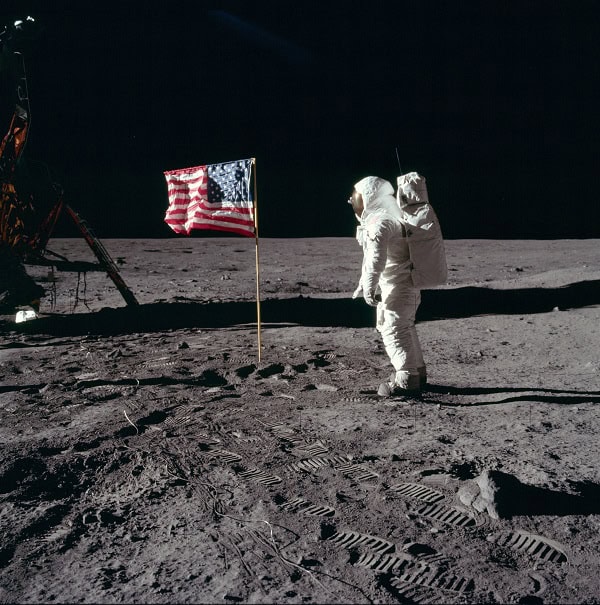

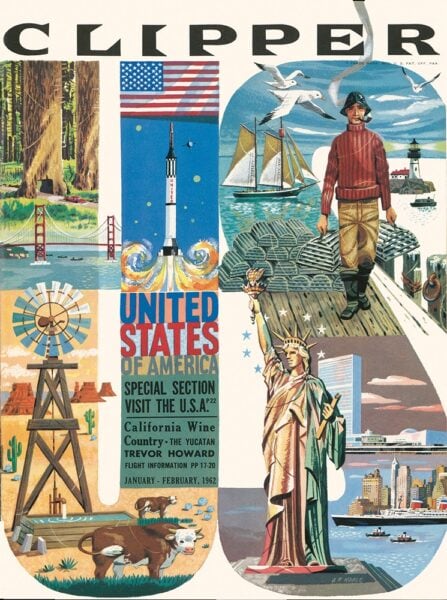

With passengers from around the world, Pan Am also advertised the United States as a vacation destination. Cover of Clipper, Pan Am’s in-flight magazine (1962). Copyright Callisto Publishers

With its legacy of dashing pilots, clean-cut attendants, and speedy flights to exotic destinations in “clippers” emblazoned with its distinct blue logo, Pan Am still holds a powerful and mythic allure. Yet its history, like aviation history in general, is about more than the glitz and the glamour that the company epitomized in its heyday—it also concerns the global spread of US culture, capital, and technology. And as Matthias C. Hühne’s new book Pan Am: History, Design & Identity (Callisto Publishers) shows, much of the enchantment surrounding the airline resulted from a corporate effort to create a visual culture that would sell the world to American consumers.

After a series of test flights, Pan Am began offering passenger service between San Francisco and Hawai`i in 1936. A round-trip flight to Honolulu cost $648 at the time. Frank H. McIntosh (1939). Copyright Callisto Publishers

Charting the rise and decline of Pan Am since its very first flight (in a hired seaplane from Key West to Havana in 1928), the book details Juan Trippe’s success in building the company into a global conglomerate, enhanced by government largesse. Guaranteed income from US Post Office mail-delivery contracts allowed Pan Am to build international routes before many other carriers. As Rudi Volti explained in Technology and Commercial Air Travel (a recent AHA publication), “carrying mail by air . . . had the important function of developing and sustaining a generation of pilots,” including Charles Lindbergh, whose celebrity was crucial in establishing Pan Am’s commercial and cultural popularity.

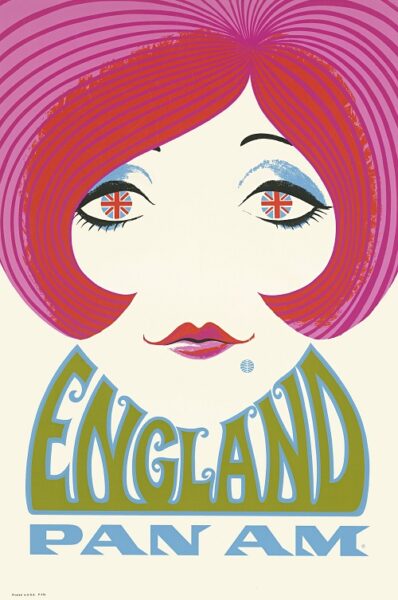

This poster advertising travel to England showcases the artistry and the talent of the many, now forgotten, designers employed by Pan Am. Notice the iconic blue Pan Am logo as the mole on the woman’s face and the British flags in her eyes. Anonymous (1969). Copyright Callisto Publishers

Pan Am’s main appeal probably lies in its reproduction of posters, timetables, brochures, and magazine advertisements that sold commercial air travel and vacations in faraway places to adventure-seeking Americans. The book provides a visual record of the history of travel and tourism: photographs of Intercontinental hotels, for example, show the importance of providing luxury accommodations in locations where upscale hotels hadn’t been built. To persuade American vacation-seekers to travel internationally, many Pan Am publications sought to educate them about the history and cultural norms of destinations outside the United States. Even if consumers could not afford such leisure, the airline’s advertising promoted appealing fantasies through a multicolor vision of foreign lands and American technological supremacy. (Though the book doesn’t mention it, racial discrimination kept air travel largely in the domain of white Americans until the Civil Rights Movement.)

Historians may include Pan Am among their guilty pleasures—readers will be largely on their own when it comes to interpreting the images, since Hühne usually provides only names and backgrounds of designers and photographers where possible. But this open-endedness is perhaps where the fun lies. Be it a route map of the Americas highlighting economic opportunities, sights, and cultural activities or the juxtaposition of a smiling American cowgirl with a demure, kimono-clad Japanese woman, the book offers a wealth of images begging for critical engagement—including in classrooms. After all, how often does the smart set meet the jet set these days?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.