As so many ideas do these days, this one started on social media.

Ahead of the 2020 election, Rhae Lynn Barnes (Princeton Univ.) shared on Twitter her thoughts about how she felt facing this moment in relation to the specter of mass death. “There was a haunting of the political discourse,” she told Perspectives. To Barnes, thinking of the casualties of the Civil War and World War II; the politicization of funerals in the civil rights movement; and even presidential candidate Joe Biden’s personal losses of his first wife, Neilia, and daughter Naomi in a 1972 car crash, as well as the 2015 death of his son Beau to cancer, “The dead were framing the conversation.”

After the disruptions of 2020, three historians worked quickly to document them in a new volume. Stephanie Martin/Unsplash

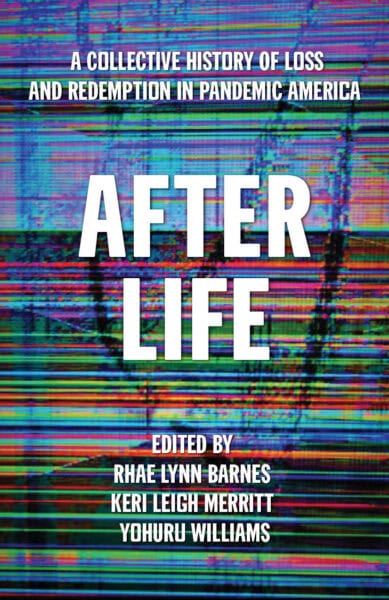

Yohuru Williams (Univ. of St. Thomas) reached out to her. “This sounds like a book project,” he told Barnes. They began talking about what such a project could look like, and contacted Keri Leigh Merritt, a historian based in Atlanta. Together, the three created After Life: A Collective History of Loss and Redemption in Pandemic America (Haymarket Books, 2022), a book, Barnes describes, “that could start out as a secondary source and ultimately become a primary source of prevaccination pandemic America.”

They call After Life a “collective history” that focuses on the events of 2020, including the COVID-19 pandemic, the uprisings that followed the murder of George Floyd, and the presidential election. The story concludes with the January 6, 2021, insurrection at the US Capitol. As the editors wrote in the book’s introduction, they were trying “to understand America in a moment that seemed at once to be both rapidly descending into something long-feared and simultaneously rebirthing into something wondrous at all costs. . . . We envisioned a book that gave historians and legal experts a chance to write about their present as long as they meditated on the long 2020 through the prism of American history.”

It was essential “to document what it was like to live through the most surreal, tragic time in our entire lives.”

According to Williams, this project builds on the work of “those individuals who have chronicled historical events as eyewitnesses to their history and active participants in it.” He was inspired by a number of points in US history: “I think specifically of Howard Zinn and his work with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or the work of the army of artists, academics, and reporters employed by the Works Progress Administration [WPA], as well as the countless state and local historians whose volumes adorn local archives and remain important sources upon which we are now quite dependent.” In working on After Life, Williams “wanted to be a part of a project that would serve the same purpose of helping scholars—one day—make meaning of this historical moment.” Despite the pressures of navigating lockdown, educating their kids at home, and even contending with personal health issues, all three co-editors, Merritt said, “knew how essential it was to document what it was like to live through the most surreal, tragic time in our entire lives.”

Williams’s comparison to the WPA is apt, as the editors took direct inspiration from that federal project. During the Great Depression, the WPA program employed 8.5 million Americans to work in spaces including the national parks, the arts, and history. Looking around during the pandemic, as a public health event led to economic depression and rising unemployment, Barnes wondered, “Why is nobody documenting this historically? Why is nobody bringing everyone together?” She saw museums on both national and local levels collecting and preserving material culture and stories, but there was no organized national effort like the WPA. Maybe she, Merritt, and Williams could bring back something like the “historian wing” of the WPA.

Committed to building a diverse group of scholars, they prioritized what voices they wanted to include over specific topic assignments. “We tried to pick people we admired as writers and essentially gave them carte blanche to write about whatever they desired,” Merritt said. “We wanted to let them be as creative as possible, because often legal and historical writing can be formulaic.” For Barnes, this choice made the project unique: “I feel like I got to take a one-on-one writing tutorial with some of my favorite authors—Martha Hodes, Robin D. G. Kelley, Philip J. Deloria—and get inside their writing process and see how they create moving and powerful stories from shards of archival evidence. It was buoying to experience this teamwork and artistic inspiration.”

For this, they turned to experts across the fields of American history and legal studies. Along with writings by the three editors, 16 historians and legal scholars contributed essays that range from personal reflections to more typical historical work. The editors’ frame makes the book a unique and wide-ranging compilation. Contributor Tera W. Hunter, for example, terms COVID-19 “a new Negro servants’ disease,” comparing it with tuberculosis in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Hodes writes about the pandemic and the Lincoln assassination, “two catastrophes, a century and a half apart.” Heather Ann Thompson focuses on how the pandemic affected the already inhumane experience of mass incarceration. In more personal essays, Ula Y. Taylor writes about how her daily Starbucks routine was disrupted, while Kelley relates his struggles writing an obituary for his estranged father, who died in February 2020.

Courtesy Haymarket Books

For a project centered on illness and death, Barnes said, “I vividly remember writing in our introduction that not all of the authors might survive. That sadly came true.” The groundbreaking historian Gwendolyn Midlo Hall contributed an essay connecting the Colfax massacre in Louisiana during the Reconstruction era to the violence of January 6. Her contribution to the volume was her last history publication before her death in September 2022 from a recurrence of breast cancer and a stroke. For Barnes, it was a “privilege to work one-on-one and line-by-line” with Hall during her final illness. A month after the book’s release, she visited Whitney Plantation during her first trip to New Orleans when she “suddenly heard a familiar voice.” Hall was featured in the prerecorded tour discussing her life’s work. “As I stood and watched, I realized I was seeing the long and profound reach of her tireless research from decades before. It made a difference. And working with her in her last days and seeing her work in that public history exhibit was a tremendous gift.”

Working with a large team of writers during an ongoing pandemic means that Hall’s was not the only illness, even if she is the only who has died. We now know COVID had medical effects beyond the virus itself, as health-care appointments and diagnoses were delayed or missed. As Barnes told us, at different times, “medical crises struck the editors, our families, the authors, and their families. I can’t list how many hospitalizations there were.” All three editors lost loved ones or people close to them during the process. Near the completion of the volume, Merritt came down with COVID and Williams had a cardiac procedure. Throughout the book’s creation, they had to rethink and rewrite to incorporate the pandemic’s ever-growing toll in the United States in real time.

To all three editors, the pandemic, racial reckoning, and electoral politics cannot be disentangled in discussing 2020. As a resident of the Twin Cities, Williams was particularly close to the actions protesting George Floyd’s murder on May 25, 2020, which influenced his perspective on the events as they unfolded. For Merritt, these events show that wealth and power continued to coalesce among the elite: “They’re expanding military-armed police forces, who brutalize and kill our loved ones with near impunity. They’ve closed hospitals during a pandemic, while building even more prisons.” To Barnes, “Pandemics and epidemics tear off the lid of American society and allow you to peer in at the wiring. Inequality becomes more exacerbated and clearer. You can’t separate the history of the body from politics or culture.”

“Pandemics and epidemics tear off the lid of American society and allow you to peer in at the wiring.”

And the events of 2020 affected people across the entire country. While death tolls rose in big cities on the East Coast, notably New York, the story doesn’t end there. Barnes, who was in New York City and New Jersey during the first six months of the pandemic, knows it would have been easy to write from that perspective. Yet if we consider the first epidemics that touched American soil, we must consider the impact on Indigenous populations. So the book begins among citizens of the Navajo Nation, where both personal narratives and per capita death rates show a major crisis in the community.

Though the book was only just released in the fall of 2022, the editors have already identified things they wish could have been done differently. With the Dobbs decision and the overturning of Roe v. Wade, medical historians who had committed to writing for the book had to withdraw in order to focus their energies on other work, but as Barnes says, “They were serving a higher good.” Williams wishes they had also included an essay on mental health after traumatic historical moments. Each editor contributed their own pieces to the volume, and Barnes has already rethought what her piece could be if written today. “My personal essay was about my experience driving across country in prevaccination America,” she said, “but if I was asked to write an essay now, it would be about my three history professor friends and colleagues who lost their lives to women’s reproductive health issues within a few months of each other in 2021 and 2022.” The pandemic means that many did not receive the usual preventive or acute medical care when it was needed, with especially dire outcomes for maternal mortality in 2021. Thus, today her contribution “would be about what happened to Maya Peterson and her daughter Priya Luna, Philippa Hetherington, and Kathryn Schwartz.”

According to Merritt, “Art is never finished. I look forward to seeing how others will interpret this project and build upon it. I simply hope we’ve inspired others, or at least provided solace and comfort to someone in need. Ultimately art is about two main things: joy and healing. And we, as a nation, desperately need both.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.