On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong became the first human to set foot on the moon. Over 500 million people witnessed the culmination of President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 goal to send a man to the moon before the end of the decade. Apollo 11 was “the largest participated-in event in history” to that point, says Teasel Muir-Harmony, curator in the Space History Department at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (NASM), breaking the broadcast record set by the Apollo 8 mission, the lunar orbital flight in 1968.

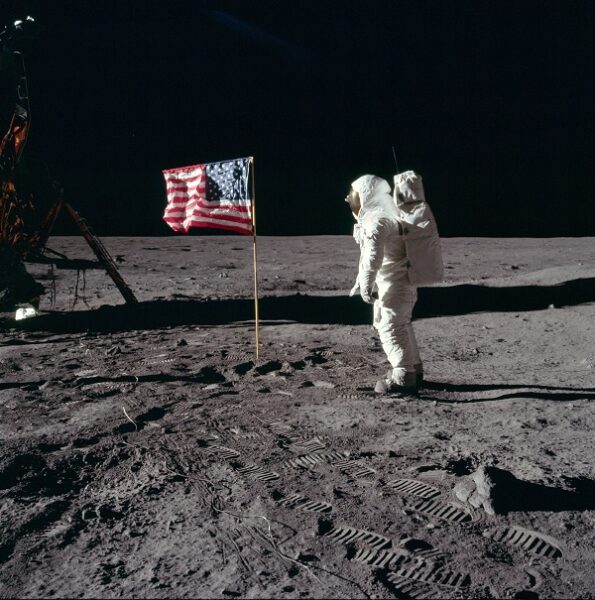

July 20, 2019, will mark 50 years since Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin (above) became the first humans to land on the moon. Neil A. Armstrong/NASA/Wikimedia Commons

Almost 50 years later, the event still resonates as a dramatic moment in history. But with the benefit of hindsight and the passage of time, space historians and the institutions they serve have begun to reevaluate the significance of the mission and Project Apollo as a whole. Informed by past scholarly works and established assessments of the moon landing and the development of space history as a field, several new publications, exhibits, and events are offering more comprehensive interpretations of the event, placing it in a wider historical and social context.

Roger Launius, former NASA chief historian and associate director for collections and curatorial affairs at NASM, says that the primary way the moon landing and the space race have been interpreted in pop culture, politics, and scholarship “is built around this exceptionalist narrative of Americans being somehow different and better than everybody else.” “We all waved the flag and were very excited in 1969 when this happened,” he says. In his forthcoming book, Apollo’s Legacy: The Space Race in Perspective (Smithsonian Books, May 2019), he presents several other perspectives on the Apollo program. Contrary to the view of the moon landing as a singular human accomplishment that is to be lauded no matter the cost, he notes that many saw and have come to see Project Apollo as being a “waste of money and effort.” Scholars and politicians on the left, he points out, have criticized the program for wasting money that could have gone toward helping people, while those on the right have argued that the funding could have supported military spending instead.

Muir-Harmony agrees. For most of the 1960s, she says, “more than half of Americans didn’t think Project Apollo was worth the money.” Instead, she says, they believed “that the US government should be spending its resources on other types of projects,” like urban housing or education. Additionally, this mixed public opinion of Apollo within the country contrasts with the support it received internationally. Muir-Harmony says that this was due in part to the fact that residents of other countries didn’t have to worry about their taxes going toward the program. In fact, Muir-Harmony says, the US government “proactively promoted and nurtured” a global audience for Project Apollo as an effort in public diplomacy.

Events such as the moon landing, says Neufeld, often “tend to be viewed in a vacuum.”

Building on more recent scholarship, NASM is planning to replace its Apollo to the Moon exhibit—which first opened in 1976, just a few years after the moon landing—with Destination Moon, a new permanent exhibit scheduled to open in 2022. Michael Neufeld, senior curator in the Space History Department at NASM and lead curator on Destination Moon, says that the older exhibit “had lots of great artifacts, but it didn’t explain very much . . . in part because it was yesterday’s news. There was an assumption that people knew a lot about it.” Since then, Neufeld says, a lot of new scholarly work has come out on Project Apollo, such as John Logsdon’s “pioneering work” on Kennedy’s 1961 decision to commit to getting a man on the moon and Howard McCurdy’s work examining space exploration in the American imagination. NASM, Neufeld adds, will draw on some of this work for Destination Moon.

Neufeld says that one of the museum’s main goals has been to “broaden” the scope of the older Apollo to the Moon. Beyond updating “antiquated museum technology and methods,” the new exhibit will be driven by the recognition that each year, a “larger and larger fraction” of museum visitors “weren’t even born in ’69 or have no recollection of it.” NASM plans to use the new exhibit as an opportunity to “tell the entire story of lunar exploration,” says Neufeld, “from ancient dreams to contemporary exploration.” This will mean contextualizing the moon landing effectively. Neufeld says such events often “tend to be viewed in a vacuum, as if they aren’t intertwined in the experience of the time.” The curators, therefore, are hoping to incorporate aspects of that context, such as the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement.

Muir-Harmony says that the exhibition will also include “more voices,” inspired by research coming from fields such as gender history, social history, and art history. In her recently released book, Apollo to the Moon: A History in 50 Objects, Muir-Harmony highlights a urine collection device as an example of technology that was “designed for men’s bodies,” with the assumption that “only men were flying in space.” The exhibition, says Neufeld, will also feature Neil Armstrong’s spacesuit, presented in a “new conservationally correct case,” the Apollo 11 command module, and the “giant” Saturn 5 engine. (The Armstrong suit had been on display in earlier versions of Apollo to the Moon, alongside Buzz Aldrin’s spacesuit, but had been removed due to what Neufeld calls “microclimate problems.”) Space art will also be highlighted in the exhibition: Neufeld says three murals will “frame the gallery space in a way that I think is going to be really spectacular.”

“The farther you get from the event, the easier it is to mythologize it,” says Launius.

In coordination with the new permanent gallery, and as part of the celebrations of the anniversary of the moon landing, a traveling exhibition featuring the Apollo 11 command module Columbia, organized by NASM and the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, has been making its way to different cities across the United States since October 2017. Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission has made stops in Houston, Saint Louis, and Pittsburgh and will move to the Museum of Flight in Seattle next April, where it will stay through the anniversary. Geoff Nunn, adjunct curator for space history at the Museum of Flight, says the museum is “pulling out all the stops to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing.” Nunn says that for its stop at the Museum of Flight, a new section added to the Destination Moon exhibit will highlight Seattle’s contributions to the space race, including lunar orbiters built by the Boeing Company that “scouted the way to map the moon to figure out where to land.” In addition to hosting the exhibition during the anniversary itself, Nunn says the museum has events planned throughout the summer to celebrate the anniversary. He says, “We’re really looking to be the place to celebrate 50 years since Apollo 11.”

Other observations of the anniversary are taking place across the United States, including at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida and the US Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama. The NASA History Division is also organizing events, including a scholarly workshop on the legacies of Apollo with the NASM Space History Department. And the AHA’s 2019 annual meeting in Chicago will include sessions on Project Apollo, including “Rethinking Apollo: Technopolitics, Globality, and the Space Age” (January 3, 3:30–5:00 p.m.) and “50 Years since Tranquility Base: Looking Back, and Ahead, from the Golden Anniversary of the First Moon Landing” (January 4, 1:30–3:00 p.m.).

Launius notes that the 50th anniversary of a major event is generally “one of the big ones, because that’s the last point where you’re actually going to have significant participants still alive.” He expects that the next year will see “celebrations and commemorations” and news articles that “dredge up various details about the Apollo program.” He also anticipates renewal of claims that the moon landing was a hoax. “The farther you get from the event, the easier it is to mythologize it,” he explains. There are now “fewer and fewer people who have firsthand knowledge of what took place,” he says. “There should be some sort of celebration.” Both Apollo 11 and Apollo 8 are the types of events, he adds, that people remember forever—“where you were, what you were doing when you heard about it, and how it affected you.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.