The Spreading Devotion: Japanese and European Religious Prints exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago.

In 1889, Chicago businessman Clarence Buckingham inherited a third of his father’s fortune. That, along with his successful career with the Corn Exchange National Bank, the Illinois Trust and Savings Company, and the Northwestern Elevated Railroad Company (for which he served as president), allowed him to continue the family tradition of collecting art.1 Clarence chose to collect, among other pieces, devotional works made in Japan and Europe.

After his death, Clarence’s sister Kate gave his collection to the Art Institute of Chicago, which still holds them today. This summer, many of the devotional prints are on display as part of the exhibit Spreading Devotion: Japanese and European Religious Prints.

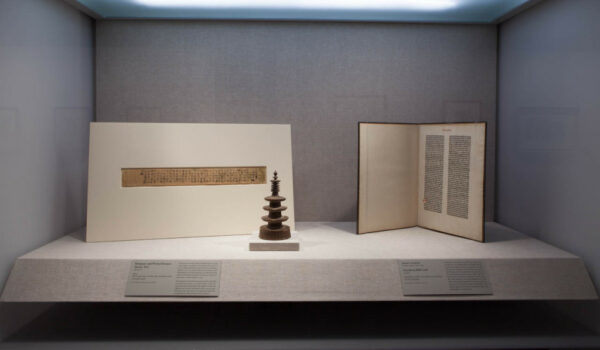

“One of the things we really wanted to bring out was this idea of printing as affecting the spread of religious imagery and religious texts,” Suzanne Karr Schmidt, assistant curator of prints and drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago, told me. In thinking about the exhibit, Karr Schmidt and co-curator Janice Katz, Roger L. Weston associate curator of Asian art, thought about the different ways in which the printing press was used for devotional purposes in Europe. The printing of religious texts started in Asia in the 8th century, whereas the first devotional letterpress text printed in Europe was made around 1454, with engraved and woodblock printed images made about a century earlier.

Left: A printed Konpon Darani (short prayer) text and a miniature wooden reliquary in the shape of a pagoda to house it, both from Japan, made around the year 770. Right: A leaf from the Gutenberg Bible, dating from 1454 or 55. The Gutenberg Bible is the first book printed using movable type in the Western world.

“We have one section with four Japanese prints ranging from the 12th to 17th centuries. They all have to do with a specific pilgrimage throughout Japan,” Karr Schmidt told me over the phone. “Each image on two of these prints represents a separate temple. It’s a little bit like a map, giving you a sense of all the sites you’d visit. The European sites weren’t quite as concentrated. There’s Jerusalem, but also many important sites within Europe.” Canterbury and Santiago de Compostela are two famous examples.

19th-century charm from Yūdonosan, Hondōji Temple, Japan. This woodblock print depicts the “Great Sun Buddha” sitting on a lotus pedestal, holding the wheel of the dharma (his teachings).

Other items on exhibit are 17th-century Japanese charms that pilgrims would buy at the Kegonji Temple at the end of a major pilgrimage route. “One of the charms includes all 33 temples, each site honoring different manifestations of Kannon, who represents compassion,” Karr Schmidt said. “Prints of Kannon were also sold separately and collaged onto a sheet as you visited each temple. As a portable piece of paper, you could bring the print with you, perhaps rolled up, as the decorative edges to the prints mimic scrolls.”

“Seeing the way the Buddhist tradition used these printed texts and images of temple statues as relics in a comparable social practice to the medieval Christian tradition of revering parts of a saint’s body is very powerful,” Karr Schmidt said. European pilgrims would touch their prints to relics at the pilgrimage sites they were visiting, transforming their prints into contact relics. The prints served other purposes as well. “There are examples where you would cut out one print [from a sheet of multiple images], and you could put it in your pocket,” Karr Schmidt explained, “Or you could sew it to your hat and have it be there for protection. It would show the religious sites you were going to or where you were coming from.”

Merchants and noblemen who did not want to go on a pilgrimage could acquire the more expensive equivalent of a coffee table book. “In the case of a pilgrimage book from 1486 in the show, they were something you would look at at home,” Karr Schmidt said. “You wouldn’t necessarily go there—you’d go on an armchair pilgrimage. That was the first time these cities were illustrated with depth and accuracy.”

Spreading Devotion: Japanese and European Religious Prints closes on June 21.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Note

- “Clarence Buckingham,” The Story of a House, August 27, 2013. [↩]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.