Editor’s Note: This is the first installment in a two-part column. The second column is available here.

Eleven miles from my family home sits the historic estate recognized by Ascension Parish locals and tourists alike as Houmas House Plantation. The site lies along the Great River Road, which runs 30 miles between the cities of Baton Rouge and New Orleans. This road connects not only the river parishes of south Louisiana but also a winding string of plantation estates. This stretch of road is, in large part, a defining feature of the river parishes I have always called home.

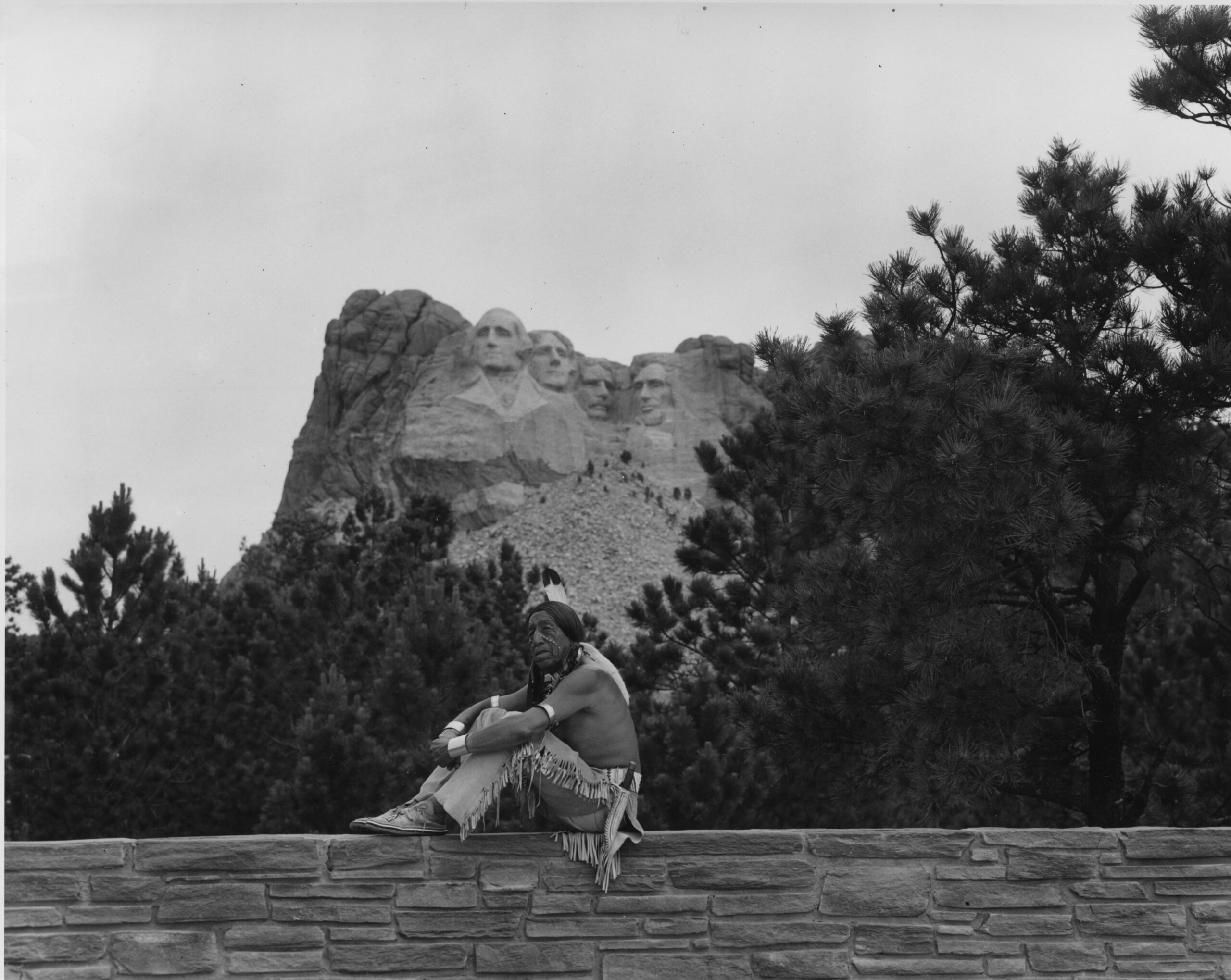

Isabel Naquin, pictured here with her grandfather Gerald Naquin, learned about her Indigenous heritage from the stories he told. Courtesy Naquin family

Growing up, my PawPaw, Gerald Naquin, a Houma man, told the story of our family’s move from the Houma-Thibodaux region to Jefferson Parish. This move distanced his family from their home and community and gradually led to their loss of language and culture. While I had long been aware of this fact, it was not until last autumn, when my Intro to Public History course led me to visit Houmas House, that I was made to contend with it. Although I understood the personal cost for my PawPaw of these losses, it was not until I visited Houmas House that I was able to understand his family’s relocation within the larger historical context and relate this event to an instance of removal in a place so central to my own upbringing.

While the distance between this plantation site and my childhood home is short, the time spanning their respective constructions embodies a path, marred by colonialism, wherein my understanding of my Indigeneity was shaped.

Inside Houmas House’s Great River Road Museum I learned, for the first time, that Houmas had once settled the land on which the site’s grounds are now located. According to historian J. Daniel d’Oney, in the 1700s the Houmas established a “Grand Village” on the east bank of the Mississippi River—where Houmas House Plantation sits—and another settlement on the west bank—today known as Houmas Point, with “other settlements [ranging] upstream and downstream.” Toward the end of the 18th century, “plantation owners and colonial officials campaigned for Houma removal.” This included pressures stemming from a “supposed land sale to landowners Maurice Conway and Alexander Latil” who claimed in court that on October 5, 1774, they paid a Houma chief named “Calabee” $150 in goods for all land east of the Mississippi. Conway and Latil, according to Houmas House, built the original two-story structure, called the French House, in 1774. This event marked the beginning of the transformation of the land from a site of Indigenous settlement to what would become by the 1850s “the center of the largest slave holding in Louisiana,” according to the National Park Service.

In the days after my visit, I reflected on how the physical site of Houmas House embodies a historic tension that defines both my heritage and the colonial landscape of Louisiana. The land my Houma relatives settled on was sold amidst pressures to expel the Houmas by my Acadian and European ancestors. In recognizing this intersection, I felt compelled to reckon with it. As a student of history, this experience underscored the importance of what Sarah Jenks has written: “Whether we are in art museums, science centers, or history museums and sites, we have an obligation to connect the stories we tell and the environments we create with the things people care about today.”

What we build atop sites of enslavement can dictate how we understand their legacy. Like the objects we display and the stories we tell about them, our landscapes, our environments, and our sites of memory are living entities. They live on in the environments that museums create and the audiences who experience them.

Inside the Great River Road Museum at Houmas House, the Houmas were addressed in platitudes, with whole centuries scaled down into sentences. Such interpretation embodies patterns of erasure, expulsion, and tensions both regional and national, that I have come to see as shaping my family’s movement and identity. In doing so, the museum has also created an environment, as Jenks characterizes, with real implications for the way Indigenous peoples may come to know themselves and their history. That the Houmas are mentioned at all created the opportunity for me to learn this piece of history, but the adherence to colonial narratives and the lack of Indigenous voices creates a space in which we simultaneously erase people of both the past and present.

While we may be quick to see museums as insular places, we must recognize the importance of representation within museums. For children, museums are a space where they learn from the earliest age about themselves and their communities. Kimberlee L. Kiehl, then executive director of the Smithsonian Early Enrichment Center, told the Washington Post, “Babies see everything. There is so much for them to look at, and for you to talk about with them inside museums.” From childhood to adulthood, the narratives shared within museum spaces ripple out from visitors into their surrounding communities. But more importantly, the presence of a museum can affect how we come to see ourselves and others. The perpetual struggle of historical work is the push and pull between methods for negating patterns of erasure. They are real, unavoidable struggles in the preservation and display of memory.

When I shared my experience at Houmas House with my class, my professor encouraged me to channel my curiosity into my studies. Since then, what began as a course assignment has come to shape my graduate studies and long-term mission as a historian. As I have sought to relearn the history of my hometown, and as I have resolved to record my family’s Indigenous history, I have begun to think about our civic responsibilities as historians. The lessons I have taken from my site visit to Houmas House have led me to see that my work, whether it be in or outside museums, will always in some ways grapple with how my descendancy straddles that of the colonizer and the colonized. Yet I have also gained an awareness of how directly the colonial foundations of historical inquiry not only shape museum spaces but also how we tell stories within them.

As a graduate student at the University of New Orleans, I am contributing to a developing exhibit at Whitney Plantation, currently named Spaces of Freedom/Stories of Resistance, wherein my mission has been to illustrate the resistance of Indigenous peoples to both African and Indigenous enslavement, all while seeking to connect these stories to descendant communities. In developing a proposed strategic plan for this exhibit, I have aimed to uncover stories, deconstruct silences, and defend against erasure by advancing Indigenous methodologies that recognize, as Amy Lonetree suggests, that “objects in museums are living entities . . . [that] embody layers of meaning, and . . . are deeply connected to the past, the present, and future of Indigenous communities.” Much in the same way Lonetree equates objects to living entities, I understand museums as living spaces too.

To my devastation, my PawPaw Jay passed last spring, taking with him stories and memories that I can no longer recover. Since his passing, my site visit has weighed heavier and heavier on my heart as I have grappled with his loss and with the newfound meaning of my hometown. Though my PawPaw is not here to answer my questions, I was comforted at the Organization of American Historians’ conference this year by the words of Jenna Mae from the Artists of Public Memory Commission during a “fishbowl” discussion on the past, present, and future of Bulbancha—a Chahta place name for “New Orleans.” Mae spoke passionately of the devastation climate change has wreaked on Indigenous lands and therefore on our ancestors who live in the environment around us. Mae’s conviction not only permitted me to believe that my PawPaw was not truly gone from me, but her words also put my site visit to Houmas House into greater perspective. Mae helped remind me why my mission matters beyond my family tree. It is not just the stories that need protecting but the environments we tell them through, for they hold meaning for the people, past, present, and future, who belong to them.

Isabel Naquin is a master’s student at the University of New Orleans, an intern at Native Bound Unbound: Archive of Indigenous Slavery, a contributing member of the Midlo Center’s script committee for the exhibit Spaces of Freedom/Stories of Resistance at Whitney Plantation, and a communications and development specialist at the Promise of Justice Initiative.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.