Editor’s Note: This is the second installment in a two-part column. The first column is available here.

As I grew up in Ascension Parish, Louisiana, my maternal grandmother often told me stories of the faith-based healing traditions practiced by her father, grandfather, and other Cajun traiteurs (treaters or practitioners) in our community. When my MawMaw Nonnie tells these stories, her recollections are as clear as her belief in this form of healing, which traiteurs, and those who believe in its power, attribute to God. Her stories reflect a culture deeply tied to local histories of refuge, settlement, and displacement, experienced by both our Acadian ancestors and my Indigenous ancestors. It is because I live in the long arc of these encounters that my visit to Houmas House Plantation last fall (discussed in my previous column) has brought me to see my home with fresh eyes.

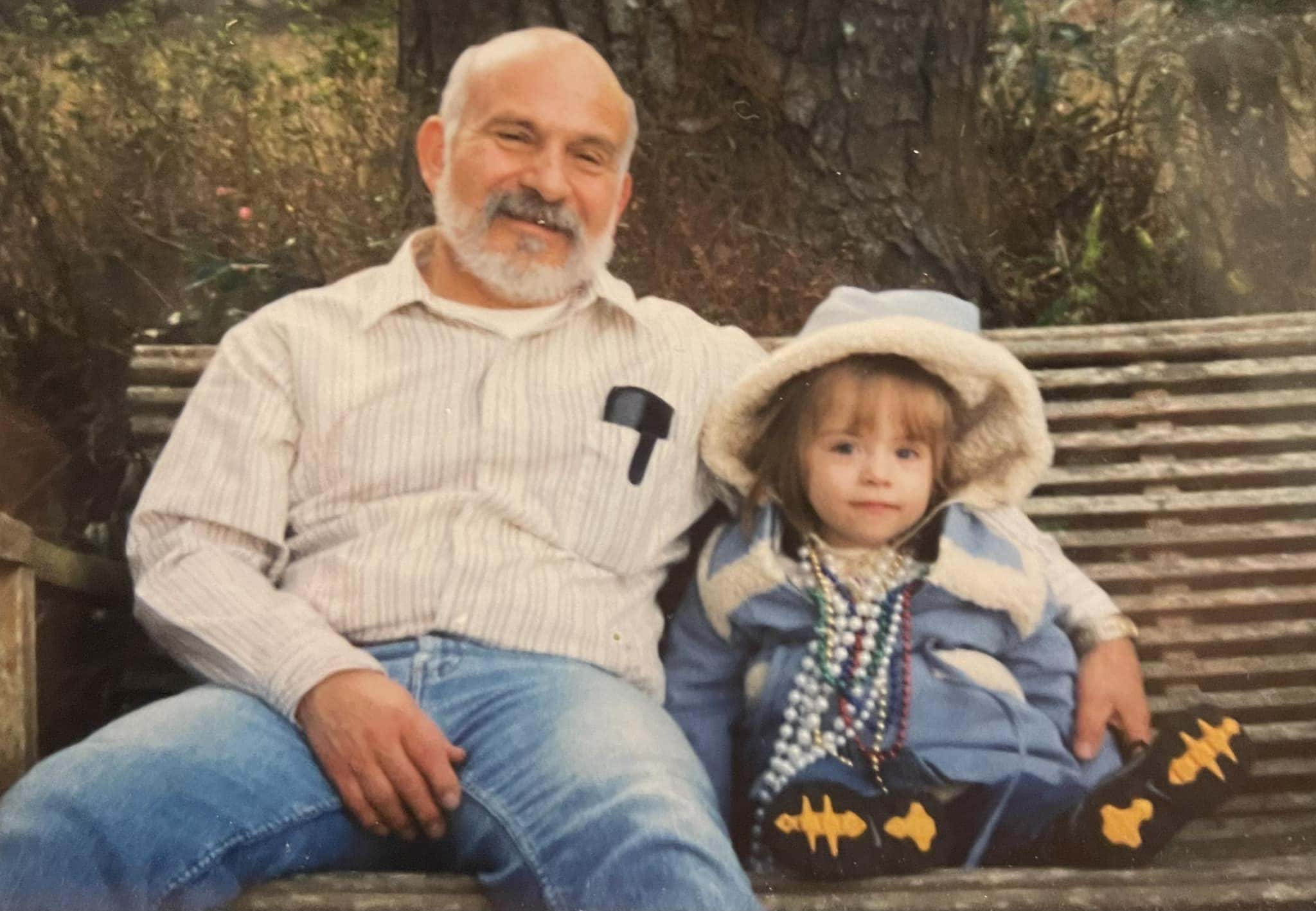

Isabel Naquin, pictured here with her grandmother Leona Frederic Babin, learned about traiteurs from the stories Babin and other family and community members have shared. Courtesy Naquin family

Since then, I have learned of another site in my parish, a restaurant turned reception venue known as the Cabin, whose building once housed enslaved peoples. Efforts to preserve, repurpose, and move this building and others like it reveal tensions between these efforts and the opportunities they create to promote mythologized histories or erase truths altogether. How we preserve and present the past plays a part in determining how it is remembered. Moreover, such efforts have incredible influence over how we form a sense of belonging. As museums consider ways to foster belonging, I believe it is necessary to consider what Francisco Guajardo, chief executive officer of the Museum of South Texas History, reminds us often draws visitors to historical sites: “[a] lifeline quest for identity, a search for name, a search for story, a search for who you are, all in this place we call a museum.”

Guajardo’s idea of a quest for belonging is the driving force behind my graduate thesis project and part of the reason I aim to center frameworks such as the Six Rs of Indigenous Research in my approach to research, interviewing, and writing. This approach is composed of respect, relationship, relevance, reciprocity, responsibility, and representation. While this framework is intended for use with Indigenous research methodologies, its principles have been a helpful guide for fostering belonging at the outset of my project. They encourage me to see people as they are, to meet them on their terms, and to validate their ways of knowing.

My project uses oral histories to explore traditional folk medicine practiced by Cajun, Creole, and Native American traiteurs.

These principles are fundamental to my project, which uses oral histories to explore traditional folk medicine practiced by Cajun, Creole, and Native American traiteurs in south Louisiana. Steeped in Roman Catholicism, this practice came to include Indigenous people who, according to Jonathan Olivier, came to be practitioners “due to colonial missionaries and contact with the French” and contributed “much, if not all, of the local plant knowledge among traiteurs.” In my initial interviews with my MawMaw Nonnie, who spoke with me about the Cajun experience, I learned just how much her knowledge of traiteurs is informed by her memories of both witnessing and experiencing this healing herself. Her testimony is a living embodiment of the many ways this tradition has been passed on and sought after by community members with faith in the power of God.

As tradition dictates, the prayers my great-grandfather said as a traiteur for those seeking his help with blood-related injuries (such as nosebleeds) or illnesses are not known to anyone except the person he chose to inherit them. As such, it is a tradition defined and sustained through alternative ways of knowing and even being, to borrow from Caroline Dodds Pennock. Concerning Indigenous ways of knowing, Pennock argues in her chapter in What Is History, Now? that where “oral histories are often dismissed as ‘anecdote’ and Indigenous elders as ‘storytellers,’ as if this were different from being historians, we must recognize alternative ways of doing, telling, and understanding the past, which may explicitly reject Western ‘facts’ in favor of traditional ‘stories,’ simply because they matter more or contain different ways of knowing.” I believe that decolonizing museum spaces requires us to embrace or, at the very least, respect these alternative ways of knowing, remembering, and believing, for they are the only way we can, as Rain Prud’homme-Cranford suggests, “consider one another as relatives, to be connected or shipped on a shared history, experience, or people” and therefore “change how we relate to one another.”

When I look at the objects in this exhibit, I see hope for making sense of my heritage and all the ways it has come to represent different ways of being.

As I have worked to incorporate these frameworks and ways of knowing into my writing, I also have taken inspiration from On This Ground: Being and Belonging in America, an ongoing exhibition at the Peabody Essex Museum that brings together and puts into conversation two collections of Native American and American art. Co-curator Karen Kramer describes the installation as an “[exploration of] the idea that there is not one way to be in this place or one way to belong.” This idea, which reads so viscerally in the display of each item, is an inspiring example of what it looks like to put these frameworks into practice and invite conversation that helps us all to make sense of the here and now. When I look at the objects in this exhibit, I see hope for making sense of my heritage and all the ways it has come to represent different ways of being.

From the phone calls my MawMaw Nonnie made to connect me with local traiteurs willing to be interviewed to the years my Aunt Pat has spent tracing our Houma genealogy, Guajardo’s notion of a quest in search of self resonates deeply for me and other family members. Just as Pennock, Prud’homme-Cranford, and Kramer have given me a way to understand my Indigeneity, so too have they given me a space to see myself as a whole person, belonging equally to the memory of my Houma PawPaw Jay and the life of my Cajun MawMaw Nonnie. As I have searched for ways to foster belonging and inclusion within my thesis project, I have found a deeper love, greater appreciation, and stronger sense of belonging to all the histories and memories that have shaped me into who I am today.

Isabel Naquin is a master’s student at the University of New Orleans, an intern at Native Bound Unbound: Archive of Indigenous Slavery, a contributing member of the Midlo Center’s script committee for the exhibit Spaces of Freedom/Stories of Resistance at Whitney Plantation, and the local history specialist for Ascension Parish Library.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.