A Soviet map of Washington, DC, showing the National Mall and the White House, 1975. University of Chicago Press

The opening of classified Soviet archives following the demise of the USSR in 1991 resulted in an avalanche of new research material for scholars of Russian history. “The Soviet Union saved everything,” wrote Gerry Gendlin in Perspectives in 1994, but he correctly anticipated that Russian authorities would be protective of documents that might betray too many secrets about the old regime. Yet where Moscow was reticent, some with access to materials proved willing to sell off tidbits. A handful of former Soviet military officers traded or sold literally tons of top-secret paper maps that eventually passed into the collections of map dealers and libraries around the world. Much of this material has been digitized and appears freely online, but almost nothing has been written about it.

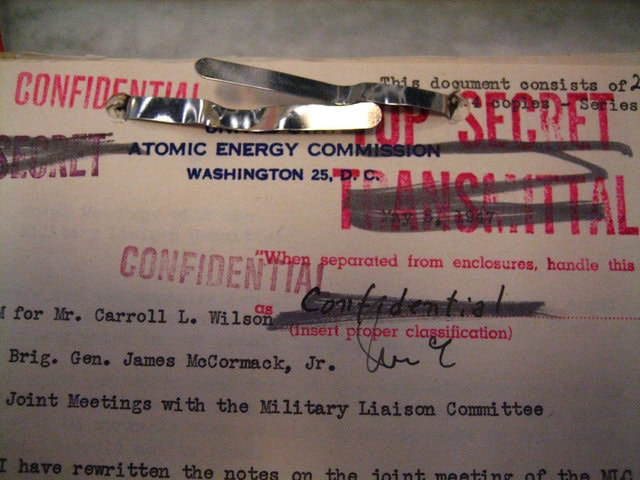

Nothing about the maps has been published in academic or general literature in the West, say the authors.

Enter The Red Atlas: How the Soviet Union Secretly Mapped the World (Univ. of Chicago Press), a new publication that unveils a treasure trove of Soviet material still largely alien to scholarly analysis. Authors John Davies and Alexander J. Kent recount “the most comprehensive mapping endeavor in history,” a secret initiative by which Stalin and his successors directed Soviet cartographers to map the entire globe with unprecedented levels of detail.

From the Second World War to 1990, Soviet mapmakers used evidence from existing national mapping projects, aerial imagery, and agents on the ground to create extraordinarily detailed maps of the very streets on which we live and work. Stalin’s investment in a highly skilled talent pool of surveyors and cartographers, argue Davies and Kent, ensured that the Soviets were ideally situated to create a technologically sophisticated geospatial resource that reflected the state’s values and aspirations.

Soviet map showing San Francisco, 1980. The Cyrillic lettering pinpoints Twin Peaks, the Mission, and Portrero Hill. University of Chicago Press

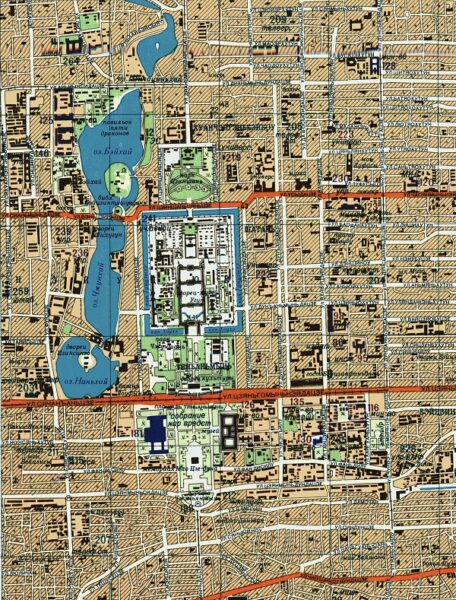

Focusing primarily on maps of North American, European, and Asian territory, The Red Atlas traces their impressive production process and strangely quiet “afterlife” following the Cold War. The book displays over 350 maps of cities, from Seattle to London to Beijing, vividly hued and brimming with topographic symbols from a groundbreaking annotation system. Most show familiar place names and cultural features spelled out phonetically in Cyrillic letters. Maps contain accurate labels of factories and the goods they produced, brand-new housing developments, river speeds, and forest heights, demonstrating that field agents had the power to gather intimate details about cities long before the proliferation of public databases like Google Maps. Railway networks in particular are hyper-emphasized, reflecting the vaunted place of the railroad in Soviet culture.

Why did these secret cartographers go to such painstaking lengths to include all this detail? The authors explained to Perspectives that the art of cartography depends on “choosing what to show and how to show it.” In the book, they conclude that since the maps “are not primarily concerned with the depiction of enemy military installations,” this “might suggest that the Soviet maps were intended to support civil administration after a successful coup.” While more evidence is needed to support this tantalizing theory, it raises interesting questions about how the USSR institutionalized its long-term ambitions to communize the rest of the world.

In a secret initiative, Stalin and his successors directed Soviet cartographers to map the entire globe.

Davies and Kent describe themselves as “British map enthusiasts,” which downplays their expertise (Davies is editor of the cartography journal Sheetlines, while Kent is a reader in cartography and geographical information at Canterbury Christ Church University). Because the creators of the Soviet maps are dead, retired, or unwilling to come forward with their stories, the duo has had to do extensive detective work to piece together how the maps were made. They’ve also had to go about it with little secondary literature to guide them.

A Soviet map of Beijing shows the Forbidden City and Tiananmen Square. Compiled 1978, printed 1987. University of Chicago Press

Public interest in Russian espionage is arguably at its highest point since the Cold War. There is no doubt that The Red Atlas, with its beautiful images, colors, and Cyrillic lettering, will ride the wave of obsession with Russian skullduggery. But while the book does appeal to a general audience, it simultaneously challenges scholars to help mine the maps’ untapped historical value. Davies and Kent hope that in the wake of the book’s publication, someone involved in the production of the maps will come forward to tell their story. “In which case,” says Davies, “Red Atlas 2, here we come!”

“We have been collecting, investigating and writing about Soviet mapping for about 15 years,” said Davies. “As far as we can discover, nothing about them has been published in academic or general literature in the West, which implies little or no awareness in academic circles of the significance or perhaps even the existence of the maps.” Davies and Kent frame their larger story with extensive explanations of cartographic techniques and specifications—allowing anyone to decipher the maps for their own research. Ironically, some of the few groups to take advantage of the maps have been foreign militaries. The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, for example, used Soviet maps found in a British library to track mountain passages and water sources in Afghanistan prior to the US invasion in the early 2000s.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.