The State Department’s Office of the Historian’s (OH’s) Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS) series, which presents the official documentary record for major United States foreign policy decisions, provides a solid foundation for students of American history. Since the series began in 1861, countless students and scholars have churned through the volumes and integrated the documents and their revelations into their work.

Publication of new volumes in the ongoing Foreign Relations of the United States series continues to be slow. Mandy Chalou, Office of the Historian, US State Department

The OH aims to publish eight FRUS volumes per year, but in 2019 succeeded in producing only two volumes, the lowest number in over a decade. This diminished level of output occurred in spite of several positive moves for the OH. It is now under the auspices of the Foreign Service Institute (FSI), a better fit for the office than its previous home in the Bureau of Public Affairs. Likewise, recent staffing changes should streamline the OH’s operations. During 2018, the OH’s position of historian (office director) was vacant; the position was filled in 2019 with the appointment of Adam Howard, previously FRUS general editor, and Kathleen Rasmussen was selected as the new general editor.

The publication drop provoked dismay among the Advisory Committee on Historical Diplomatic Documentation (HAC), which monitors the OH’s progress on the FRUS series as well as the State Department’s declassification procedures and guidelines. The HAC is composed of representatives from several scholarly societies, including the AHA, as well as a few at-large members. Its members have significant experience with declassification policies and are well qualified to flag problems with the current processes.

In 2019, the OH faced challenges on multiple fronts. In their concerning annual report—another in a line of alarming reports—the HAC heavily criticized the Department of Defense (DoD) for its slow pace of declassification review, which stymied the review process of the FRUS series. The HAC also remains troubled over the capacity of an already-strained National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) to keep up with the forthcoming deluge of electronic records.

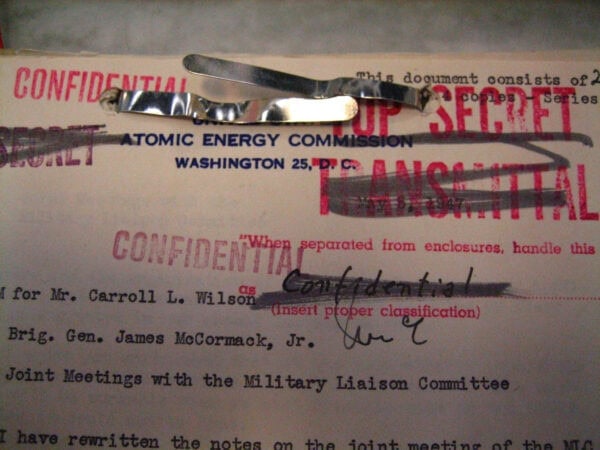

FRUS encapsulates the declassification pacing problem. The State Department must release a classified document no later than 30 years after it was written, provided that, upon review, it is deemed to no longer contain sensitive information. The Foreign Relations Statute “requires publishing a ‘thorough, accurate, and reliable’ documentary record of US foreign relations no later than 30 years after the events that they document.”

DoD has continued to cause problems for the FRUS process.

A few persistent issues explain the decrease in the number of volumes published, with declassification woes among the most serious. An increasing number of documents selected by the OH for the FRUS series include sensitive intelligence information. Frequently, several departments hold “equity” in the records and “are entitled to approve or deny their release in part or full.” For many agencies, the same declassification offices handleFRUS reviews and time-sensitive Freedom of Information Act and Mandatory Declassification Review requests, which take priority. Due to this protracted interagency process, the declassification progress can be glacial.

Despite these concerns, the report sees some bright spots in the process. The HAC praises the declassification efforts and the FRUS series volume review of the State Department’s Office of Information Programs and Services (IPS), which “should serve as a model for other agencies and departments.” The report also lauds FRUS review and declassification work completed by the Central Intelligence Agency and the National Security Council’s (NSC’s) Office of Records and Information Security Management.

In contrast, the DoD has continued to cause serious problems for the OH’s FRUS series process. Indeed, the report states, “the NSC was pivotal to resolving a seemingly intractable dispute between the OH and DoD over one particular volume when National Security Advisor John Bolton intervened directly to support the OH’s request to refer the volume to the Interagency Security Classification Appeals Panel.”

Both the 2018 and 2019 reports condemn the DoD for “egregiously” violating the deadlines set out by the Foreign Relations Statute for a declassification review of a FRUS compilation (120 days) and responding to appeals of the first review (60 days). In 2019, the DoD “responded to less than one-third of the volumes that the OH submitted for its review, it took more than four times longer than the mandated timeline when it did respond, and its few responses were of poor quality.” The report concludes, “OH’s inability to publish more than two volumes in 2019 can be attributed largely if not exclusively to DoD’s failure to provide timely and quality responses.”

The Office of the Historian made significant strides in digitization.

The HAC sees some reason for hope, however, explaining, “The Defense Office of Prepublication and Security Review, which coordinates FRUS declassification reviews within DoD, came under new leadership in 2019. Far more frequently than in past years, this new leadership attended HAC meetings, providing fuller briefings, and pledging to do whatever was within its limited authority to improve.” But the report notes that for DoD to successfully get “OH back on the path of meeting the statutory timeline for publishing FRUS volumes,” it will need the sustained “commitment and direction of high-level DoD officials.” The report warns, “The progress OH has made toward reaching the mandated 30-year timeline has stalled. Indeed, the gap is likely to begin to widen again.”

The OH has received strong support from the FSI, and FSI’s efforts to engage the DoD on these issues comes in for praise. The HAC recommends that senior State Department and DoD officials work together to establish a centralized FRUS declassification coordination team. Such a team would be instrumental in meeting DoD’s declassification mandate.

Thanks to successful collaboration by the HAC and the US Armed Services Committee staff, the National Defense Authorization Act of 2019 included a provision requiring “the Secretary of Defense to submit a report to Congress on the ‘progress and objectives of the Secretary with respect to the release of documents for publication in the Foreign Relations of the United States series or to facilitate the public accessibility of such documents at the National Archives, presidential libraries, or both.’” Compiling such a report, the HAC explains, should encourage greater transparency by DoD on its declassification delays and other performance issues, “an important step in precipitating improvements.”

In other good news, the OH made significant strides in digitization. Over a 10-year period, the OH digitized all 512 previously published FRUS volumes, completing this effort in 2018. The FRUS digital archive, freely accessible online, now total 307,105 documents, drawing from 538 volumes published between 1861 and 2019. The digital archive is searchable by full text or date, and individual volumes can be downloaded as e-books. In 2019, the OH embarked upon a project digitizing the microfiche supplements released between 1993 and 1998 of documents from the Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy FRUS subseries, completing work on the supplements on arms control, national security policy, and foreign economic policy during the Kennedy administration.

The US Department of State is headquartered in the Harry S. Truman Building in Washington, DC. AgnosticPreachersKid/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0

In addition to overseeing the OH’s work on the FRUS series, the HAC monitors the State Department’s review and transfer of records to NARA, and NARA’s progress accessioning and processing the documents. Similar to its comments on the FRUS series, the HAC report identifies mixed progress for the State Department’s record-keeping and declassification process.

The 2019 report reiterates concerns the HAC raised in 2018 about the impact of budget-driven staff reductions on the quality and speed of NARA’s work accessioning and processing State Department records. In fact, this year the committee notes that these concerns “have if anything become more acute.” As the report explains, these problems will only intensify given a 2019 memorandum issued jointly by NARA and the Office of Management and Budget that “directs all agencies to manage in their entirety their permanent records electronically by December 31, 2022.” Beginning in 2023, NARA will no longer accept paper records, leading to what the HAC anticipates will be “an explosion of electronic records” that will further strain the capacity of both the State Department and NARA.

The HAC explains, “This policy confronts each agency with an unfunded mandate that, in an era of constrained budgets, staff shortages, and an urgent need to purchase advanced technologies, imposes a cost that creates a severe burden on them.” The IPS shared with the HAC its paper on the modernization program, praising NARA for developing benchmarks toward a fully digitized records-management system. But the HAC notes with concern that the IPS paper ignored the hefty costs the modernization program will entail, and the potential risks of rapidly transitioning from paper to fully electronic records management.

The IPS has promised to hold full briefings on the modernization program in 2020, and the HAC plans to raise questions about the costs and risks at these briefings. In addition, the HAC recommends that NARA and the IPS solicit public comment on the plans.

Finally, the report notes that the Presidential Library System has been negatively impacted by budgetary and staff shortages as well, leading to delays with the processing and classification review of emails from the Reagan and George H. W. Bush administrations. The report warns, “Solving these problems is central to the future research needs of FRUS compilers and the public at large.”

The FRUS series and the State Department’s records remain vital to fulfilling the federal government’s commitment to transparency and an informed public. By continuing to sound the alarm over declassification and records-management problems in its reports, the HAC provides a crucial service. These documentary records bring to light the twists and turns of the history of American foreign policy that would otherwise remain shrouded from the public.

The HAC’s 2019 report can be found in its entirety here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

.jpg)