As historians, we think of archives as belonging to our collective selves. Documents, images, and ephemera, carefully described, placed inside manila folders, and housed in gray boxes, are part of the lifeblood of historical research.

Chemawa Indian School Baseball Team, 1939. Bureau of Indian Affairs, National Archives Identifier 5585776

But professional historians—whether as archivists, curators, interpreters, teachers, or writers—are only one group that uses an archive. This is hardly a surprising revelation. When we spend time in a reading room, we regularly encounter other patrons. But have you ever stopped and looked around the room and wondered just who the other researchers are? What brings them there? And what stories do they hope to find? The mandated silence of the reading room doesn’t lend itself to this kind of discovery.

But the impending sale of an archival facility does.

In January 2020, the federal Public Buildings Reform Board, an obscure federal agency established in 2016, announced that the building housing the National Archives at Seattle would be sold to the highest bidder. Its records would be transferred out of the region to facilities in southern California and Missouri. The proposed sale drew an immediate outcry, eliciting responses from individuals, tribal nations, lawmakers, and organizations, including the AHA. One year later, in January 2021, the AHA joined a coalition led by Washington State Attorney General Bob Ferguson in filing a lawsuit to prevent the facility’s imminent sale. This broad coalition includes the states of Washington and Oregon; 29 tribes, tribal entities, and Indigenous communities from Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Alaska; the City of Seattle; and eight museums and community and historic preservation organizations.

The National Archives at Seattle, the Pacific Northwest’s only National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) facility, maintains and provides access to millions of permanent records created by federal agencies and courts for Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington that date back to the 1840s. Among them are tribal and treaty records relating to the 272 federally recognized tribes located in these states, as well as records tied to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1872. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), National Park Service, and US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) are among the dozens of federal agencies whose Pacific Northwest records are housed in this facility. These records contain more than bureaucratic stories; they reveal the broader history of the region and maintain significance not only for historians, but for many communities across the region and beyond. Yet when the Public Buildings Reform Board decided to sell the facility, none of these communities were consulted. As Charlene Nelson, chairwoman of the Shoalwater Bay Tribe, asked during a public comment session on Zoom: “Where are our voices in this decision? Where are the sounds of our drums?”

“Where are our voices in this decision? Where are the sounds of our drums?”

As part of the AHA’s participation in State of Washington et al. v. Russell Vought et al., I collected statements from professional historians and AHA members testifying to the critical role played by the Seattle facility in Pacific Northwest scholarship and education. Those seven statements were among the 79 declarations submitted as part of the lawsuit. These declarations and a public comment session in January, attended by more than 300 people, made clear the diversity of people and professions that rely upon access to the Seattle archives. Their archival research stems from a broad array of interests, work, and activism, ranging from obtaining tribal recognition, to forest and natural resource management, to researching history dissertations and producing exhibits, to exploring a family’s past, to reconnecting to culture that was subjected to erasure.

The facility is a critical research and internship resource for students and faculty in the region. Its records support the reinterpretation of signage at historical sites and, as one local researcher noted during the public session, enable small towns to research their history in support of the tourism industry that is central to their economies. For some archive users, the stakes of maintaining access to the records in the Seattle facility are very high. Veterans and their families access records to support applications for benefits. BIA records are critical in local tribal communities’ legal cases, ranging from federal recognition of a tribe to protecting fishing rights.

Joshua L. Reid (Univ. of Washington), for instance, uses the archives for both his own publications and the research he does in service to federally recognized tribal nations related to conservation, natural resource use, and treaty rights. Minutes from tribal council meetings, photographs of Makah fishing vessels, letters from federal agents, field notes, and maps with marginalia informed Reid’s “expert witness report and testimony on behalf of the Makah Nation’s efforts at exercising their treaty rights through a petition for a waiver to the Marine Mammal Protection Act,” as he wrote in his statement.

The Seattle archive also houses original case files for people who entered the country through ports in Portland and Seattle during the period of Chinese Exclusion. Those files are critical links for Chinese Americans looking for information about their ancestors, as well as important research material for groups such as the Chinese American Citizens’ Alliance of Seattle, which is developing educational modules to educate the public about the Chinese Exclusion Act’s impact on the community and region.

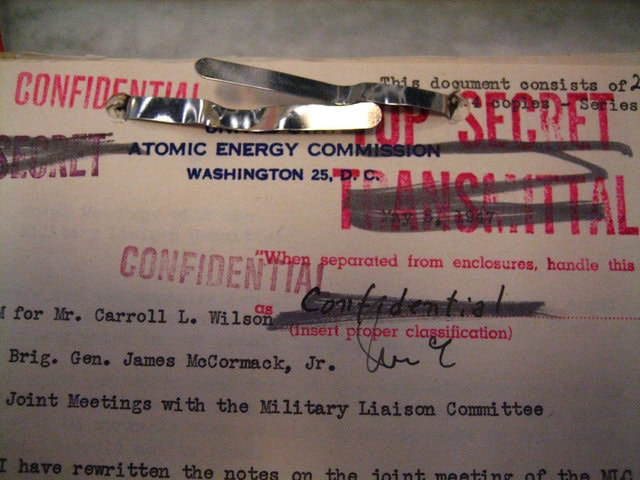

I searched from my Maryland desk for digitized sources that would help me convey the compelling relationships of Pacific Northwesterners to the history housed in the National Archives at Seattle. I wanted to show Perspectives readers the letters written by Ryan W. Booth’s (Washington State Univ.) great-great-grandfather asking the Chemawa Indian School superintendent to send Booth’s great-grandma home for the summer, or the blueprints of this school—which was centered on an assimilation-based curriculum—that are “so large that they filled an entire table.” I would have liked to include some of the documents that helped Lissa Wadewitz (Linfield Coll.) uncover the “actions of fishermen, smugglers, and government officials trying to control what quickly became a volatile and chaotic fishery” along the US–Canada border. But none of those records have been digitized. And that’s part of the problem.

Digitized records do not provide the equivalent to an in-person research experience.

When the NARA facility in Anchorage, Alaska, closed in 2014, its records were transferred to Seattle, with the promise that they would be digitized and accessible in Alaska. That process has begun, but digitization is slow, costly, and particularly difficult to achieve when NARA has been underfunded for years. Indeed, according to NARA’s Seattle director, Susan Karren, only “0.001% of the facility’s 56,000 cubic feet of records are digitized and available online.” The Chinese Exclusion files, for instance, are not only undigitized, but also sorted only by Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) numbers—not by individuals’ names—making them difficult to use. As a result, volunteers are painstakingly working with the paper files to create a more usable index.

While digitization is a powerful preservation and access tool, digitized records do not provide the equivalent to an in-person research experience. As Andrew Fisher (William & Mary) wrote in his statement, “There is great value in being able to sit and browse through boxes and folders by hand. Many of the discoveries a historian makes in the archives are serendipitous, as pieces of evidence crop up unexpectedly in folders where you would not necessarily have looked for them.” That process of sitting and browsing not only leads to discoveries, but also improves archivists’ knowledge of collections.

This sort of piecing together of collections and records groups is familiar to researchers working on Indigenous histories. Robert Kentta, a member of and cultural resources director for the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, notes that “research and investigation of the Siletz Tribe’s history often involves going back and forth between different groups of records to cross-reference obscure and brief references to a particular incident, area of subject matter or tribe and band.” This research is particularly complicated because the Siletz Tribe is composed of more than 28 bands and tribes, who were dispossessed of lands stretching from northern California to Washington and removed to the Siletz Coast Reservation in Oregon in 1855.

The ability to follow leads across different records groups—to trace a topic from the records of the BIA to the FWS to the INS—is a learned skill. The National Archives at Seattle has been a critical resource for undergraduates and graduate students attending universities in the Pacific Northwest, as well as the faculty who teach them. Those institutions have developed strong programs in Pacific Northwest history and Indigenous studies in part due to the region’s ability to support such research topics through its archives. As Reid put it: “If this regional NARA facility is closed, I will be unable to train graduate students at using valuable federal records on topics related to tribal nations in the Pacific Northwest—they simply will not be able to adequately pursue these kinds of topics.”

Chin Quan Chan Family Identification Photograph, 1911. Bureau of Immigration, National Archives Identifier 5585730. Image cropped.

The statements, written by archivists, civil rights activists, educators, genealogists, history faculty and graduate students, museum professionals, tribal chairpersons and members, and people searching for their own histories, reveal the central role the National Archives at Seattle plays in the region. As Coll Thrush (Univ. of British Columbia) wrote, for scholars, tribal researchers, legal professionals, and the public, the ability to use these archives “has meant the difference between a rich scholarship on the region and a lack of collective knowledge about the area’s ongoing histories; between tribal sovereignty and the ongoing marginalization of Indigenous communities; and between the protection of key environmental resources and their continued depletion.”

The planned transfer of the Seattle facility’s records out of the region would render public access to the records extremely difficult, if not impossible, for millions of users. Gabriann Hall (Central Oregon Comm. Coll.) likened it to “someone removing a sacred photo album that has been passed down through generations from one’s home. It does not mean that the family photo album would not be safe, but it would no longer be accessible to enjoy and share among the family.”

While the sale of the Seattle facility was halted by a temporary injunction in February 2021, the lawsuit is ongoing, and the coalition’s work is not yet done. The ultimate goal is to keep the records in the Pacific Northwest, so that, in the words of Hall, “the chance to come together and look at the album and hear stories and learn collectively” will not “be lost.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.