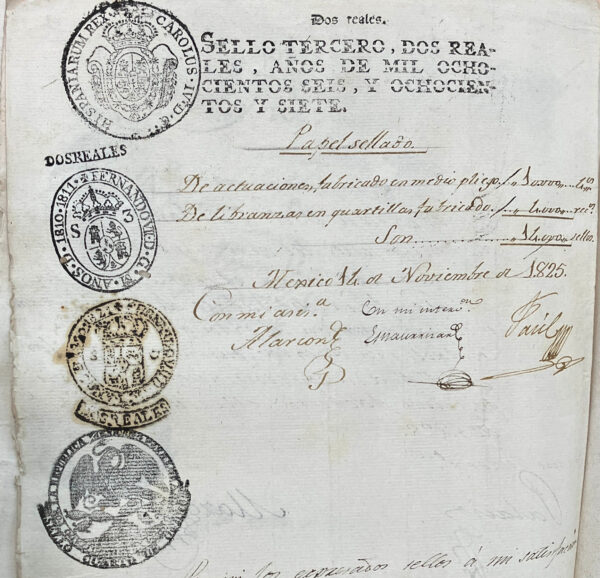

This document caught my eye while I leafed through a sheaf of papers in Mexico’s national archives. I was reading accounts prepared by government functionaries in 1825 in Mexico City, just a few years after national independence. But my eyes soon shifted to the margins, cluttered with stamped seals descending the edge.

Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico. Hacienda Pública / Papel Sellado / Caja 4 / expediente 11.

At the top are several medallions featuring crowns, a coat of arms, and the names of two Spanish kings; at the bottom, an eagle grasping a serpent, encircled by blurry text that named La República Mexicana. Here, I realized, was a story about the momentous changes that accompanied the unraveling of the Spanish Empire in the Americas, visualized in a succession of stamps. It was also a tale of continuity, about how functionaries of the new nation-state, despite trumpeting the rupture with Spain, reused old materials to build a new political project.

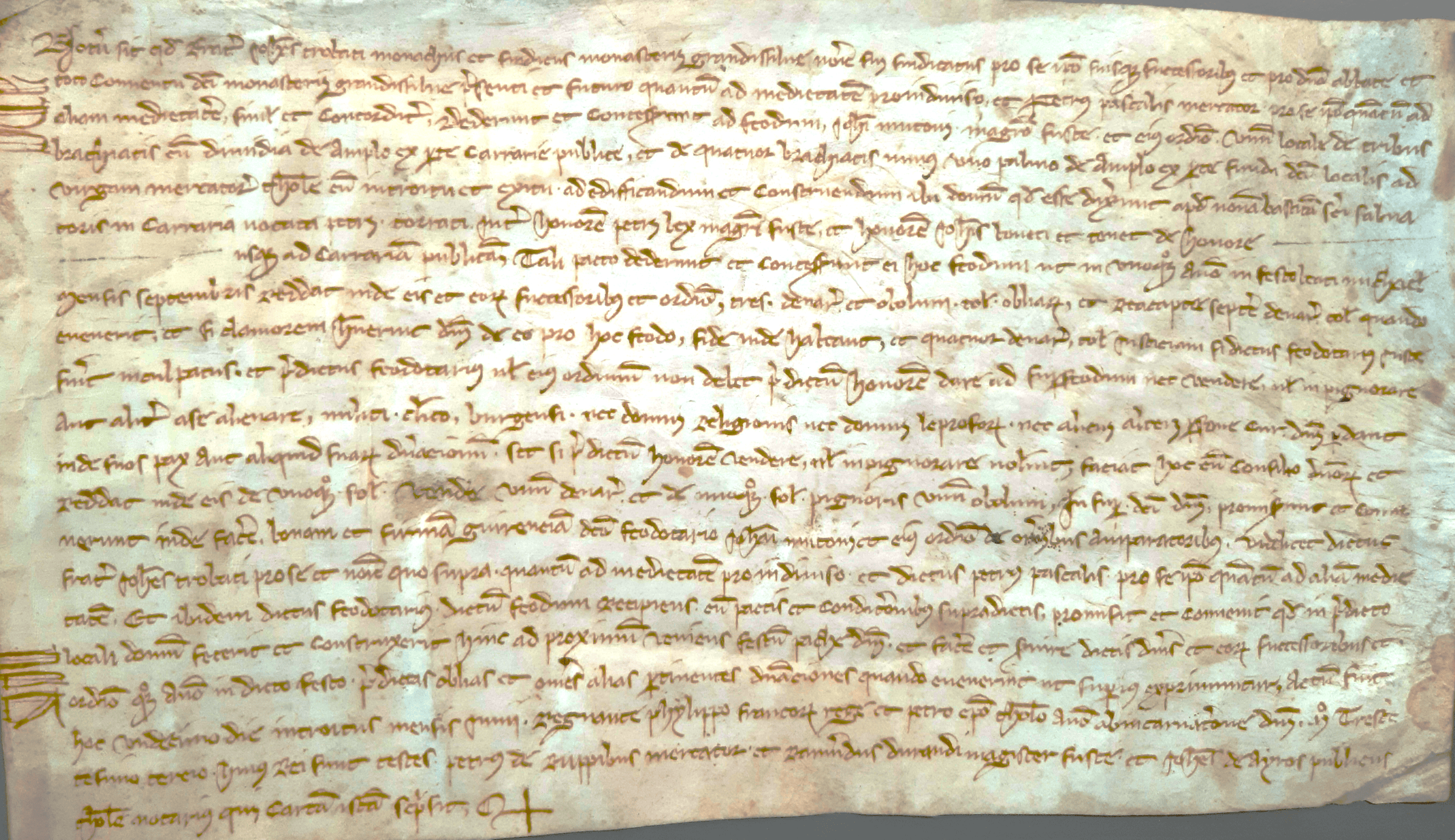

Spain’s sprawling early modern empire ran on paper. Beyond administering paperwork, an army of scribes helped ordinary people navigate the justice system and conduct official business. Resulting texts were registered, beginning in the mid-17th century, on papel sellado, a stamped paper issued by the crown. Requiring this paper for key transactions—like wills, contracts, or legal petitions—gained the crown important tax revenue. Many European empires adopted stamped paper, generating grumbling and even fueling explosive anticolonial protests in the 18th-century Atlantic world. Its ubiquity impressed a certain “look” on Mexico’s colonial archives, which are filled with sealed documents. The example here shows the basic formula. Across the top, under a small cross, text proclaims that this is third-class paper, costs two reales, and is valid for use in 1806 and 1807. To the left is the coat of arms of King Carlos IV, reiterating the crown’s authority to issue this official paper.

The seals’ story continues in the next two descending stamps. Fernando VII ascended the throne. And clearly, officials produced more papel sellado than they used during 1806–07, because the sheet was stamped again for 1810–11 and a third time for 1820–21. The “reseal” of 1810 indexes the loyalty and endurance of the viceregal regime amid imperial turmoil: in 1808, Napoleon had invaded Spain and deposed Fernando VII, but on this sheet of paper, the king continued to rule. He was restored in 1814, and thus reappears in the 1820 stamp. Resealing as a common practice, meanwhile, reveals a world where it made more sense to restamp an unused sheet of paper than to throw it away. Imported European paper was not to be wasted.

The story takes a dramatic turn with the final stamp. The Napoleonic invasion triggered a crisis of legitimacy in the Spanish Empire. Over a tumultuous decade, a drawn-out struggle for independence culminated in 1821 with the creation of a short-lived Mexican Empire and, in 1824, a new republic. In the final stamp, the new nation’s coat of arms—the eagle clutching a serpent atop a cactus—again reseals the sheet for 1824–25. Gone were the castles and rampant lions of European nobility. Instead, Mexican leaders embraced neo-Aztec imagery that evoked a pre-Columbian empire’s foundational myth. In 1825, two decades and four seals later, someone finally used this particular sheet of paper: an administrator organizing the new branch of government tasked with making and distributing papel sellado. At the end of empire—or, at the beginning of a new national story—Mexico embraced papel sellado, appropriating a familiar taxation method and ensuring that the republican archives resemble their colonial predecessors.

Administrative seals may seem peripheral to a document’s content. Yet this sheet’s stamps speak to the material realities that accompanied broader processes of political change. In 1824, Mexico had a flashy new symbol—but also an economic crisis, making the old regime’s paper, still sitting in the capital’s warehouses, more valuable than ever. Until Mexico could secure its own paper supply, bureaucrats embraced the leftover materials of empire to begin a new project of nation building—by adding a final stamp.

Corinna Zeltsman is assistant professor at Princeton University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.