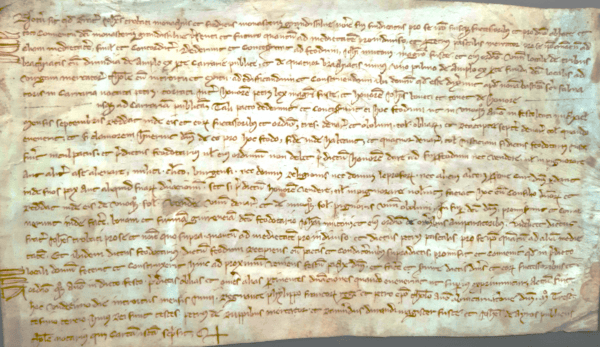

At first glance, a document in box 108 H 17 from the Archives départementales de la Haute-Garrone in Toulouse, France, is as boring as its name suggests. An eight-by-five-inch parchment with 21 lines of Latin text written in a neat hand and in a script typical of the early 14th century, it is indistinguishable from millions of items in archives across Europe. Its contents, too, are banal: John Trobati of the monastery of Grandselve and the merchant Peter Paschal Torraci announce that they have given in fief to John Mutton, master builder, an area some three and a half brachia wide and four brachia and one palm deep in the new planned town of St. Salvator, all for a yearly rent of three denarii and one obolus. The contract then lays out the stipulations for holding, renting, or selling the property, and concludes with a clause dating it to June 11, 1303, and giving the name of the public notary, John de Ayros, who wrote it.

Courtesy Archives départementales de la Haute-Garrone

The oddities in the document appear only by comparison, requiring me to read thousands of others just like it to notice them. Here are some: the plot is being given in fief jointly by two representatives, one clerical and one lay, of the king of France. The town is new, since Mutton must build a house on the plot quickly, by next Easter. He may not sell, rent, or give the plot to anyone with the resources to mount a legal suit: a knight, cleric, town citizen, religious house, or leper house. The yearly rent is cheap, but the price for transferring the land to an heir is high, making the property difficult to inherit or sell to anyone but the original owners. Social relationships in the medieval West that are preserved for posterity in legal contracts were organized around the process of creating ties of mutual obligation, usually through grants of land, a process often (and wrongly) called the feudal system. But here is a legal contract that is more concerned with protecting the grantors’ property rights than creating feudal ties, and that inhibits the purchaser from creating such ties himself.

There is another strangeness to note: in the description of the plot’s location, the name of one of Mutton’s new neighbors is left blank.

The blank space in the contract suggests a final oddity: it’s not just a contract but a very early example of a blank form. Medieval legal contracts abhor blank space. A blank space is a space where some clever scribe might insert an additional clause. A good scribe or notary would even put periods on either side of any number—for example, .VI.—to ensure that no one might change it later. If Mutton had no neighbor, the scribe should just omit that clause, since such contracts were drawn up either during or after a transaction. Moreover, several other contracts from St. Salvator also survive, all with the same unusual stipulations and pricing structure, all for plots the right size for a city house, and all issued in a tight two-month window. Thus, the contract was drawn up ahead of time as part of a large set of near-simultaneous sales on a new urban development with the specific names to be filled in as purchases occurred, and no one had yet purchased the neighboring plot.

It is strange to think that something so ordinary as incomplete paperwork could portend the beginnings of modernity. But regular plot sizes and rents on plots that are hard to sell or bequeath in new towns like St. Salvator, combined with generic paperwork drawn up in advance, cannot mark a special, feudal relationship between a vassal and their lord. They are instead a first step in the creation of the abstract, impersonal relationship between a citizen and their state.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.