The Great Patriotic War, as the Soviet Union dubbed its battle with the Third Reich and its European allies from 1941 to 1945, was a life-and-death struggle with a genocidal enemy. Over eight and a half million Red Army soldiers and an estimated 12 to 20 million Soviet civilians died in the conflict. It was also the Soviet Union’s greatest victory, providing the regime with a new narrative of legitimacy: the state and people uniting to save the world from fascism.

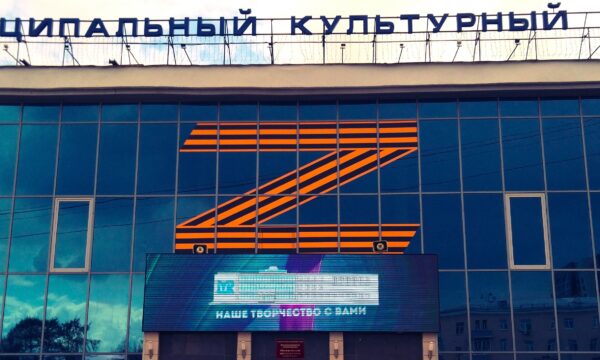

Alexander Davronov/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0 (image cropped).

In Russia today, one of the most ubiquitous embodiments of the cult of the Great Patriotic War is the St. George’s Ribbon. These orange-and-black strips of cloth, which vary in quality and size from about a foot in length to the facade of a whole building, have been distributed throughout Russia on the eve of Victory Day (May 9) since the 60th anniversary of World War II in 2005. They were initially an apolitical sign of solidarity with the disappearing generation that fought in World War II and pride in the Red Army’s key role in defeating fascism.

The ribbon design contained several layers of meaning. Its striking orange-and-black color scheme—“the colors of smoke and flame”—was used in older Russian and Soviet medals. These colors were used for the Victory over Germany medal, issued in 1945 to all soldiers in the Red Army and featuring Stalin’s profile. Prior to that, the same colors appeared on the Order of Glory, a medal supposedly designed by Stalin himself in 1943 to recognize rank-and-file soldiers. The Order of Glory in turn consciously imitated the Order of the Great Martyr and Victorious St. George, instituted by Catherine the Great in 1769 and known colloquially as the St. George’s Cross.

The many parallels between the Soviet Order of Glory and the Imperial St. George’s Cross were part of a conscious policy to reestablish connections to a romantic past. The Soviet regime publicized the Order of Glory, and after the war, black-and-orange ribbons became a standard decoration on postcards celebrating the victory. Despite regime changes, the color scheme thus celebrated bravery and victory regardless of ideology.

In the 21st century, the ribbon has taken on new ideological meaning. When mass protests broke out in Moscow in 2011–12, regime supporters wore St. George’s Ribbons, drawing on Kremlin-based narratives that saw protesters as foreign agents and NATO as the inheritor of the Third Reich. In 2014, Russian-backed separatists in Donbas, declaring the Ukrainian state fascist, used the St. George’s Ribbon to identify themselves. Finally, when Russian troops poured over the Ukrainian border in February 2022, turning what had been a limited conflict into a war, slogans such as “Zа победу!” (“For victory!”) and “Zадача будет Vыполнена!” (“The Mission will be fulfilled!”) began to appear in the colors of St. George’s Ribbon. Eventually the letter Z in this color scheme became a symbol of Russian support of the war, appearing on people’s chests and cars and as massive displays on the sides of buildings. The war has elevated the St. George’s Ribbon to the status of “symbol of military glory.” Insulting or defacing it can lead to fines of up to three million rubles and three years in prison, making the ribbon a legally protected symbol of Russian military glory from time immemorial to the present.

A year into the war in Ukraine, the St. George’s Ribbon has become intertwined with the conflict and Putin’s interpretation of history. He has posited the West as a continual, existential threat to Russia, of which the Third Reich was simply the most radical, honest version. Russia has been able to mobilize heroes to defend itself in every incarnation—Empire, Soviet Union, or Federation. St. George’s Ribbon is part of a continuous narrative that ignores the dramatic ruptures and regime changes since 1917, Ukrainian sovereignty, and many darker moments of the region’s history. Instead, this symbol foregrounds battlefield glory over suffering, embodied in a distinctive ribbon that anyone can pin to their chest.

Brandon Schechter is a teaching resource developer at the AHA.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.