Patrick Loughney is the executive director of the Library of Congress National Audio-Visual Conservation Center, and he is worried. “During the 20th century, the US produced more films and sound recordings than the combined output of the rest of the world’s nations,” he stated in an e-mail, yet despite the leap forward in technology and storage, we are facing a future of “staggering” loss. There are some 46 million sound recordings held in public institutions such as museums and archives, with millions more in the hands of private entities including recording companies, collectors, and broadcast companies. Many more have been lost and still more are inaccessible due to copyright or other legal restrictions barring their reproduction. “It is an illusion to believe that ‘all’ audiovisual works of the past are available on the Internet or soon will be,” continued Loughney, “and that the qualities of the copies of such materials as are available equates to adequate preservation of those works.” The Library of Congress’s recently released National Recording Preservation Plan (NRPP) provides a roadmap for these critical audio artifacts that, notably, links preservation with access.

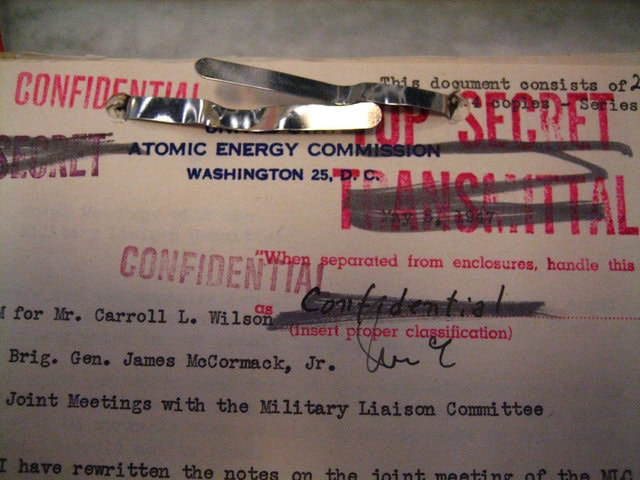

A badly deteriorated Memovox disc, a grooved CAV audio disc format made of thin sheets of cellulose acetate. This recording is unplayable and permanently lost. Library of Congress Photo/Abby Brack Lewis.

According to the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center’s website, “Of all sound recordings released in the US from the 19th century through the end of 1965, more than 85 percent are no longer commercially available to the public.” To address this problem, Congress passed the National Recording Preservation Act in 2000, intended to both “implement a comprehensive national sound recording preservation program,” and “increase accessibility of sound recording for educational purposes.” Because so many audio artifacts are in private hands, the NRPP was developed through a public-private partnership, and organized into six task force groups comprised of music industry executives, digital technologists, music historians, musicologists, librarians, and archivists. The resulting plan provides 32 recommendations covering infrastructure, preservation, access, education, and policy strategies.

Much is at stake here for American historians. Music and broadcast programs comprise much of our recorded heritage, but there are also other, lesser-known kinds of recordings that make up a significant sector of the at-risk material. These include presidential speeches, field recordings, National Press Club talks, and countless interviews, some of which may have been transcribed, but without capturing the nuance and characteristics of their original audio format. And what has been lost, from the earliest wax cylinder recordings to the cockpit recording inside the Enola Gay, cannot be restored. Although digital technologies offer promising avenues for archiving and preserving recordings, various barriers to access have prevented both the public and the preservation entities from protecting what is left.

The link between preservation and access to the materials is an important one. As Loughney notes, “One of the mantras of motion picture and recorded sound archivists is that ‘access promotes preservation.’ Audiovisual collections are among the most ‘locked up’ of the research materials in any archive or library for a number of reasons,” including complicated and outdated copyright restrictions that have discouraged or outright prohibited reproduction. The problems of reproducing and preserving audio recordings are different than those of other kinds of artifacts because there was no federal copyright protection for published recordings until 1972, leaving those recordings, in the words of the report, “protected by a complex network of disparate state civil, criminal, and common laws.” As a result, libraries and public institutions are reluctant to reproduce older materials for the public because they are not in the public domain or because it is unclear how the “fair use” doctrine may apply. For this reason, several of the NRPP’s recommendations concern revising or overhauling copyright law to bring pre-1972 recording under federal copyright.

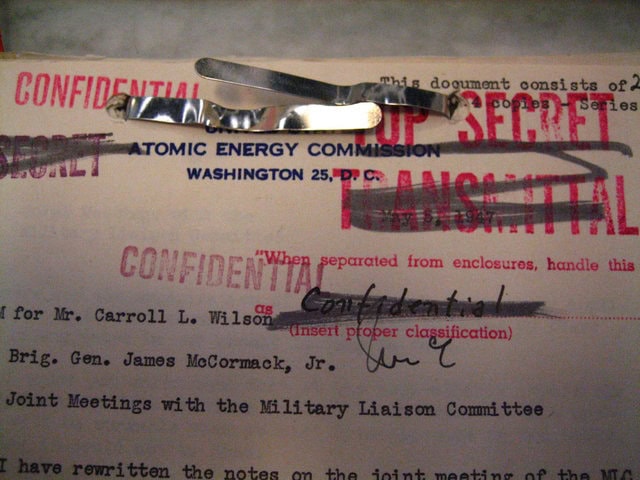

An audio engineer monitors the playback of a 16″ lacquer disc. Library of Congress Photo/Abby Brack Lewis.

Aside from the legal obstacles, there are the technical challenges of extracting preservation-quality audio from an overwhelming variety of original formats, and recommendations in the NRPP also address the need for expanded technical training. Loughney also feels there is a stigma attached to audio materials and that some feel they “constitute items of ‘popular culture’ that are not worthy of preserving to high archival standards.” Lastly, there is no comprehensive way to search for recordings that do exist, and the lack of copyright records, from which such data might be compiled, makes this a difficult undertaking.

The National Recording Preservation Board addressed these challenges in the plan, not as discreet tasks to be executed separately, but through an integrated approach. A key component of the 2000 act stated, “public investment in the preservation of sound recordings can benefit the public only if they can access those materials.” Subsequently, the recommendations in the NRPP combine public access through licensed streaming and a national directory of sound collections with the more conventional notions of preservation through material conservation, dedicated storage, and audio preservation education. The plan also calls for a number of regional preservation and licensed streaming centers to be established around the country. The library’s National Jukebox application already streams over 10,000 recordings from the library’s website, including speeches by Presidents Taft, Harding, and Wilson, but the NRPP advocates regional centers where researchers can access many more via streaming.

The library’s own audiovisual conservation facility, the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center, also known as the Packard Campus in Culpeper, Virginia, is a state of the art building that houses 6.3 million collection items (1.2 million moving images, 3 million recorded sounds, 2.1 supporting materials). The facility, which houses preservation, conservation, and storage facilities, is the home of the Preservation Film Board as well as the Recording Preservation Board. It models the approach laid out in the NRPP in the way that it combines public access and preservation, by providing year-round free screenings of films in the national registry. As for the future of this ambitious plan, Loughney states, “Efforts are now underway to engage the members of the library’s National Recording Preservation Board, and the national organizations they represent, in assuming responsibility for implementing one or more of the 32 recommendations in the Plan.”