The Zika virus currently spreading throughout the Americas is the latest of several dangerous pathogens communicated from person to person by a mosquito called Aedes aegypti. Other species from the genus Aedes might be competent vectors (i.e. transmitters or carriers) as well, but so far the evidence fingers aegypti as the main culprit.

Before 1492, Aedes aegypti did not live in the Americas. It came from West Africa as part of the Columbian Exchange, probably in the context of the transatlantic slave trade. It gradually colonized those parts of the Americas that suited its feeding and breeding requirements, and for centuries served as the primary vector for yellow fever and dengue, viruses that are cousins of Zika.

Aedes aegypti is a peculiar and fussy mosquito. It has a strong preference for human blood, which is rare but not unique among mosquitoes. That makes it an efficient human disease vector. It likes to lays its eggs in artificial water containers such as pots, cans, barrels, wells, or cisterns. (At times it was called “the cistern mosquito.”) This unique preference distinguishes it from the thousands of other mosquito species, and presumably reflects an adaptation millennia ago to opportunities presented in West Africa by human water storage in pots and perhaps gourds. Aedes aegypti is, in effect, a domesticated animal, rarely found far from human settlement and stored water—it is mainly an urban mosquito.

The history of yellow fever gives clues about the spread and domain of Aedes aegpyti in the Americas. The first clear yellow fever epidemic ravaged the Caribbean beginning in 1647. By the 1690s, the mosquito had colonized landscapes between southern Brazil and the Chesapeake, and yellow fever broke out from time to time in the warm latitudes of the Americas (like most mosquitoes, Aedes aegpyti needs warm weather to flourish). In the 18th and 19th centuries, both Aedes aegypti and yellow fever appeared in summertime as far north as Quebec and as far south as Buenos Aires. Aedes aegpyti could not handle winter conditions in Quebec, but was at least now and again brought by ship in summertime and succeeded in establishing a local population as long as warm temperatures lasted. Thus for 250 years, Aedes aegypti thrived in the warm latitudes of the Americas and, when brought by ship, occasionally prospered in summer months elsewhere. In those years, from 1647 to 1900, it brought great misery in the form of yellow fever and dengue, killing hundreds of thousands of people.

“Latest From The Front — Our Friends The Mosquitoes Preparing And Off For The Summer Campaign.” New York Public Library Digital Collections.

It was not until the end of the 19th century, however, that medical researchers came around to the view that mosquitoes might be the ones spreading these diseases. The first to publish the idea that Aedes aegypti carried yellow fever was a Cuban doctor, Carlos Finlay. His hypothesis proved correct, borne out by experiments undertaken by US military doctors led by Walter Reed. Armed with this knowledge, the US Army in its occupation of Cuba and Panama made life miserable for Aedes aegypti. The mosquito’s egg-laying preferences made it comparatively easy to control—cover up all water containers; put a drop of kerosene into those you can’t cover. Within a couple of years US authorities banished yellow fever from Cuba and Panama’s Canal Zone through successful mosquito control. The writing was on the wall for Aedes aegypti.

Over the next 70 years or so, mosquito control acquired ever more weapons. Insecticides, such as DDT—brought to bear in the 1940s—proved effective against all mosquitoes (and other creatures too). Aedes aegypti, because it likes human settlements and not the deep jungle, fell victim to spraying campaigns more easily than did most other mosquito species. Continued covering, or emptying, of artificial water containers, also put a damper on the birth rates of Aedes aegypti.

As often happens in public health, however (in vaccination regimes, for example), Aedes aegypti control proved too successful for its own good. Once the mosquito populations had fallen drastically, and the risk of yellow fever and dengue diminished, the logic of paying for continued mosquito control weakened. Budgets needed for other things were redirected away from mosquito control all over the Americas. On top of that, the nasty side effects of DDT and other insecticides became well known in the 1960s, further undermining support for spraying.

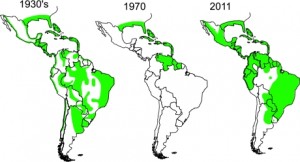

Because of all this, Aedes aegypti has made a dramatic comeback in the Americas since the 1980s. While the main reason is the lapse in mosquito control, a smaller reason is the warming climate, which slowly extends the range of the mosquito. Had the Zika virus come to the Americas in the 1930s or 1950s its prospects would have been poor—competent vectors were hard to find and mosquito control was robust. But today, its chances of spreading widely among human populations are far better, thanks to the recent resurgence of Aedes aegypti in the Americas.

Combatting Zika in the short run will require mosquito control. While work on a vaccine has begun, typically such efforts take years to bring useful results. In the meantime, targeting the vector makes the most sense. Today it is harder for public health authorities to impose rules on people than it was, for example, in the Canal Zone in 1900–05. It is also harder to spray with insecticides such as DDT, knowing their effects on human health and the environment. Zika would probably have to do much more damage to people before a strong consensus in favor of these methods of mosquito control could emerge again. More feasible today, perhaps, are efforts at mosquito control involving genetic manipulation that produces male mosquitoes whose offspring almost all die quickly. Small-scale trials in Brazil and elsewhere have brought encouraging results. Although there are skeptics wherever genetic manipulation is involved, at present there is no organized political force opposed to that approach and the necessary biological tools already exist. So this may be the most promising way to combat Zika.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.