Almost exactly 100 years ago, on the eve of the Scopes Trial, celebrity prosecutor William Jennings Bryan stumbled across the core question for any issue of religion in US public schools. The State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes was about more than just banning evolution, Bryan insisted. The real question was broader: “Who shall control the public schools?” The US Supreme Court wrestled recently with the same fundamental question. In the end, the six-justice majority not only repeated Bryan’s century-old wrong answer; they didn’t seem to quite understand the question.

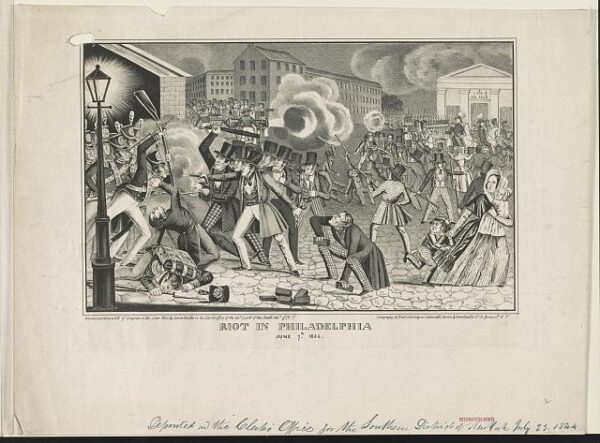

Disagreements over religion in the public schools led to violence in 1844 Philadelphia. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division/public domain

The case in question, Mahmoud v. Taylor, might seem far removed from the debates of the Scopes era. For one thing, the conservative religious parents in this case were not evangelical Protestants like Bryan and the overwhelming majority of Tennesseans in 1925, but rather a mix of Muslim, Catholic, and Ukrainian Orthodox believers. And though many conservatives today yearn to ban ideas that are critical of conservative ideology, in this case the parents were trying only to opt their children out of some required schoolbooks. Parents in this case argued that their right to freely exercise their religion was harmed if their children read books presenting gay and transgender characters in a positive, affirming way. Back in 1925, no one was even considering the issue of LGBTQ+ representation in public schools.

Yet today’s landscape of school culture wars is broadly similar to the aggressive conservative push of the 1920s. States are mandating religious chaplains in public schools, fighting to install displays of the Ten Commandments, and in Oklahoma at least, pushing a return to teaching the Bible “as an instructional support.”

Moreover, at heart the fundamental question is the same. When it comes to religion and public schools, the United States has never been able to find a satisfying answer to the question of control. We have never figured out who should be able to decide if and how to teach religion. States and schools have tried everything: They have tried mandating religious devotions for everyone. They have tried banning them for everyone. And usually, in the best traditions of American public education, they have muddled through: requiring or banning religion but allowing opt-outs for those who cannot or for those who must.

When it comes to religion and public schools, the United States has never been able to find a satisfying answer to the question of control.

This last option can be attractive, as it apparently seemed for the conservative justices on today’s US Supreme Court. The history is clear, however. Opt-outs have always served an important purpose as a kind of emergency patch to cover a fundamental problem, but they can be more than difficult. They can be downright dangerous.

In the first half of the 19th century, for instance, the school district of Philadelphia tried to accommodate its growing population of Catholic students. The Catholic hierarchy objected to the use of the King James Version of the Bible for mandatory Bible readings. For their part, Protestant activists objected to the option of the Douay version, with its Catholic-friendly commentary.

Unable to see a way out, in 1834 the school district tried a please-no-one compromise by banning all religious practices. The board threw up its hands at the “utter impossibility of adopting a system of religious instruction that should meet the approbation of all religious societies.” Then, due to fierce protests from both Catholics and Protestants, the school board flip-flopped and returned to mandatory Bible readings—King James Version only—with Catholic students allowed to opt out. By 1844, this awkward nonsolution became utterly unmanageable, as one teacher told the school board. Her attempt to lead students in Bible-reading led to “considerable confusion,” she told the board. Not only did Catholic students disrupt the class in their exit from the classroom, but many of them simply kept going and left the school entirely.

Even worse, Catholic students were beating up Protestant students, and vice versa. The violence did not limit itself to the schoolyard. The entire city exploded. Literally, in some cases, with Protestant militias marching into Catholic neighborhoods, leveling houses and churches with a cannon, and refusing to retreat until the US Marines marched in to restore order.

Martial law was an extreme result of botched opt-outs, but the solutions did not get any easier in the 20th century. By the mid-1950s, Pennsylvania public schools still required Bible reading and teacher-led prayers. One family, headed by Edward Schempp, objected. Even when the state allowed his children to opt out of the prayers, Schempp protested that the practice left his children feeling like “odd balls.” He worried that their objection would be mislabeled as “atheistic communism,” putting the children at risk of being shunned or even assaulted at school. Eventually, the Supreme Court agreed, ruling in the 1963 Abington Township v. Schempp decision that any school-mandated religious practice was unconstitutional.

By the 1980s, some conservative evangelical Protestants objected to the religious environment of post-Schempp public schools. In Hawkins County, Tennessee, Vicki Frost and a group of concerned parents examined the required literature textbooks and found them actively hostile to their religion. The books, Frost complained, encouraged ideas such as the idea that “all men are brothers,” offending Frost’s religious conception of divinely created differences. They included excerpts from books such as The Wizard of Oz, which Frost considered blasphemously occult due to its depiction of good witches. One story, Frost’s ally Bob Mozert warned, depicted a boy cooking dinner, ignoring the “God-given roles for the different sexes.”

Originally, the school board was very supportive, with all members sharing similar conservative evangelical Protestant religious beliefs. The school district tried to compromise by offering opt-outs, but things quickly got out of hand. Frustrated with what she saw as the tepid support of administration, Frost encouraged her children to disrupt their classes by refusing to read when asked by the teacher. In the end, the elder Frost child and nine other students were suspended for their in-class behavior.

Yet Frost still had a great deal of community support. More than that, she had the support of Ronald Reagan’s White House, with the Department of Education pressuring textbook publishers to offer books with more “traditional moral character development.” In the end, however, the federal court of the Sixth Circuit rejected Frost’s complaint in 1987, ruling that children’s right to free expression of religion was not harmed by mere exposure to different ideas.

For centuries now, opt-outs have often served as the least-bad solution to an impossible situation. But they require a specific toolkit.

Today’s Supreme Court has done more than flip that sensible ruling on its head. By deciding that parents have a right to opt their children out of curriculum that they find offensive, the six conservative justices have demonstrated a terrible ignorance of the relevant history. For centuries now, opt-outs have often served as the least-bad solution to an impossible situation. But they require a specific toolkit. To make them work, students, teachers, parents, and administrators all need to rely on close relationships built on personal trust. They all need to be flexible and demonstrate a willingness to compromise.

In Mahmoud, today’s court has instead insisted that conservative religious objectors need not compromise. They need not work within the delicate framework of curricular requirements. By simply saying no, any parent can—in practice—exert control of their public school. No school will be able to offer tailored curriculum for every child, so schools will be pressured to eliminate any topic that any parent finds objectionable. Parents will be able to fulfill the flawed dream of William Jennings Bryan; they will be able to create schools in which any challenging idea can be simply blocked and banned.

It’s always tricky to predict the future, but in this case one prediction seems clear and obvious: Schools will struggle mightily to fulfill their basic functions in such an environment. What will they do when two students (or their parents) have conflicting objections? How can they help students master core concepts if parents won’t allow students to learn basic ideas in literature, science, history, or math?

The Supreme Court did not need to divine this future to see how impossible their solution will be for the nation’s public schools. They could have simply looked to the past.

Adam Laats is SUNY Distinguished Professor of education and history at Binghamton University, State University of New York. He is the author of several books, including The Other School Reformers: Conservative Activism in American Education (Harvard Univ. Press, 2015) and most recently Mr. Lancaster’s System: The Failed Reform that Created America’s Public Schools (Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2024).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.