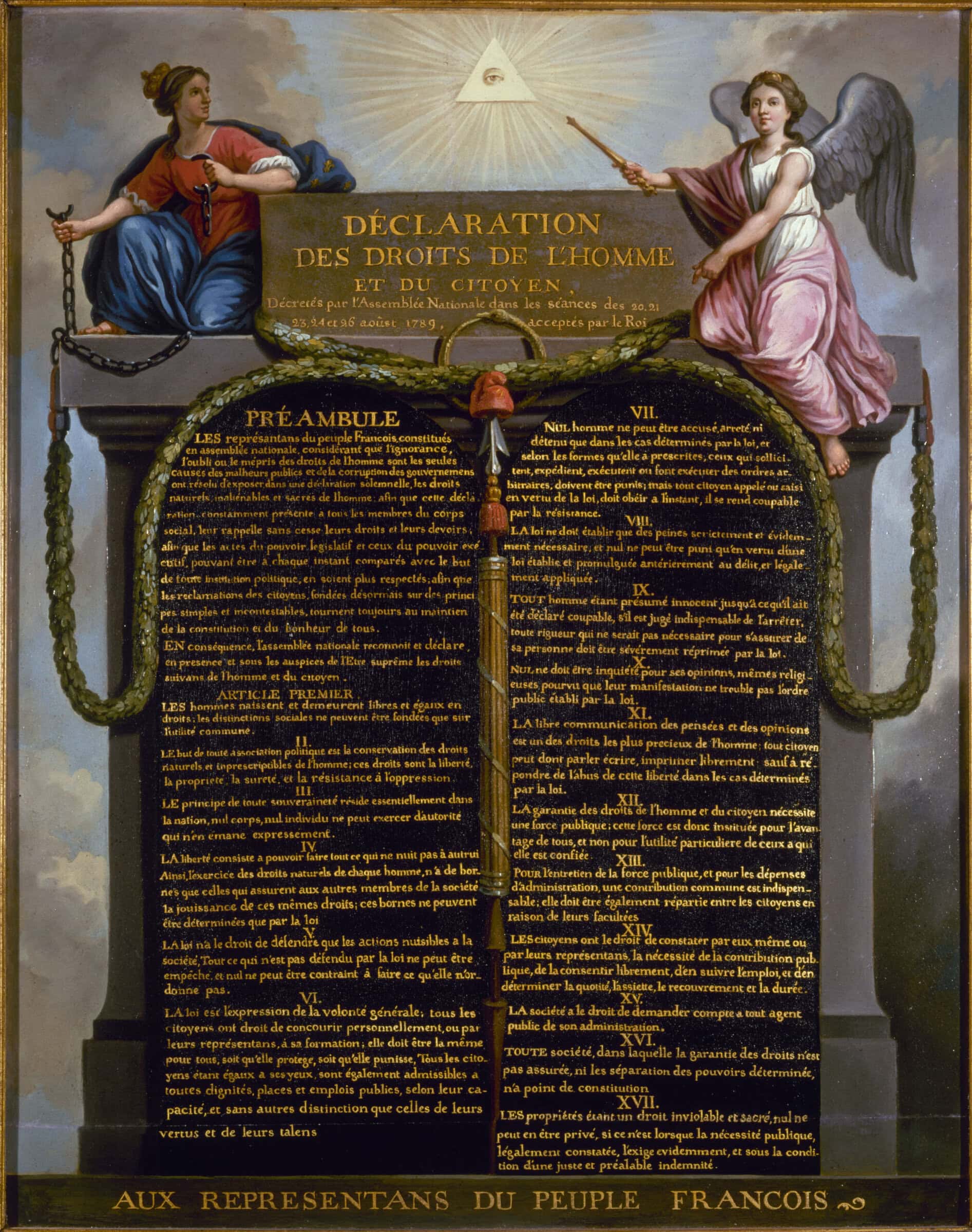

If you have been on social media in recent months, you have probably encountered long-dead historical figures staring back at you, blinking, and tilting their heads with animatronic detachment. These eerie living portraits were created using Deep Nostalgia, a new app from genealogy website My Heritage that animates images using AI. Less than a week after the app’s release, users had already uploaded more than 8 million images, animating everyone from Neanderthals to Jesus Christ.

With Deep Nostalgia, users can animate images of loved ones, ancestors, and notable figures like Abraham Lincoln. Deep Nostalgia

Deep Nostalgia is just one example of the “deepfakes” to be found online. Generally speaking, a deepfake is a video that has been altered using machine-learning algorithms to show hyper-realistic people saying and doing things that they never said or did. Some videos seamlessly transplant one person’s face onto another person’s body, while others create an entire person from scratch. The living portraits produced by Deep Nostalgia are relatively shoddy, and thus qualify as “cheapfakes,” but the most advanced deepfakes are difficult if not impossible to detect with the naked eye.

The first deepfake to gain widespread attention was released in 2018. The video appeared to show Barack Obama saying, “Donald Trump is a total and complete dipshit.” In fact, the video was an effective PSA from director Jordan Peele about the dangers of deepfakes. Acting as an invisible marionette, Peele used the Obama avatar to caution viewers about the potential dangers of deepfakes. In the years since, several other deepfakes have also gone viral. Perhaps you’ve seen the video that shows Bill Hader morphing into Arnold Schwarzenegger, or the one that places Will Smith’s face on Cardi B’s body.

It is not yet clear how deepfakes will influence the historical discipline, but opinions run the gamut. Some researchers believe that historians will ultimately find deepfakes to be useful, even benevolent. Legal experts Danielle Citron and Robert Chesney have heralded their pedagogical potential, insisting that deepfakes might liven up otherwise boring history lectures. Others have leveraged deepfakes to explore alternate histories. For example, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology produced an award-winning short film in 2019 called “In Event of Moon Disaster,” which featured a deepfake version of President Nixon seated at his desk, solemnly informing the nation that the Apollo 11 astronauts had perished on the moon. A related website includes teaching resources that helps viewers learn more about media literacy.

Some researchers believe that historians will ultimately find deepfakes to be useful, even benevolent.

As a teacher, I can see how historians might use apps like Deep Nostalgia to great effect. Students could research and write historically informed scripts, which they then use to animate different historical figures. They could stage well-sourced debates between historical figures from different eras. In other words, we could design lesson plans and assignments to match the medium, in much the same way many teachers now ask students to create memes, Twitter threads, and unessays about the course material.

Even so, the preponderance of evidence suggests that there are legitimate reasons for concern. After all, malicious actors have long proved willing to mischaracterize the historical record in service of ideology. Consider the fraudulent Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which has fueled anti-Semitism for more than a century despite its clearly fabricated origins. More recently, studies have shown that white supremacists routinely co-opt and misrepresent research on genetic genealogy to suit their racist worldviews. One can only imagine how neo-Confederates and neo-Nazis might attempt to revise the historical record with help from deepfakes. It should concern all of us, no matter our political affiliation. Truth decay benefits no one but demagogues and anarchists.

Similarly concerning, deepfakes will generate different reactions depending on the context in which they’re viewed. Consider the Nixon deepfake. Though it was first displayed within the context of an art exhibit, the film is now available on YouTube. Given that millions of Americans already doubt that the moon landings ever took place, it is easy to imagine that some may think the deepfake is real when they stumble upon it without context.

Truth decay benefits no one but demagogues and anarchists.

These issues stretch beyond the historical. Research has shown that microtargeted deepfakes can have a real effect on political attitudes. We have seen that credulous mobs of political zealots are susceptible to persuasion, and a well-timed deepfake could easily incite violence. Still, those threats remain largely hypothetical. For others, the deepfake menace is much more acute. Historians are people first, and we cannot simply ignore the unsettling fact that 96 percent of all deepfakes on the internet depict nonconsensual pornography, and that 99 percent of deepfake porn targets women. As such, women are more likely to be victims of deepfakes than Obama or Trump. As the number of deepfakes continues to skyrocket, some observers fear that deepfakes herald nothing less than the “information apocalypse,” the very “end of reality.”

Facing these daunting prospects, what can historians do? For starters, we can take heart that scholars in the digital humanities are now in the midst of a well-documented “visual turn,” and that many of our colleagues are well prepared to meet this moment. Rapid advances in machine learning and computer vision are transforming how historians engage with photographs, videos, and other visual media, including everything from Civil War photos to classic sitcoms. We can’t expect computational historians to confront and defeat the deepfake specter by themselves, but their work can help all of us learn to use computational tools to examine visual media from humanistic perspectives.

Historians lacking in programming skills can assist in other ways. For example, we can help demystify deepfakes by showing that earlier technologies, from the printing press to photographs, engendered similar concerns. In each case, observers worried that new technologies would undermine not only historical evidence but also the very concept of testimony itself, and in each case, they were proven wrong. (Whether we believe our reassurances is another matter.) We can also apply our research skills toward questioning, verifying, and contextualizing the provenance of any given video. Ironically, we may also be called upon to vouchsafe the physical archives, distinguishing genuine artifacts from fake ones. In short, we need to actively protect the historical record if we hope to keep it real.

Abe Gibson is an assistant professor in the Department of History at the University of Texas at San Antonio. He tweets @AbrahamHGibson.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.