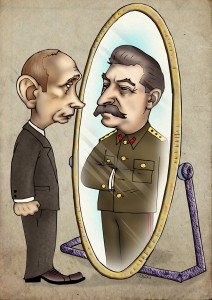

To what extent are Vladimir Putin and today’s Russia recapitulating the tsarist and Soviet past? As Russia roared back into the headlines with the war in east Ukraine, the 2014 annexation of Crimea, and an authoritarian crackdown that has trumpeted antagonism toward the West, popular discussions in this country have frequently portrayed contemporary Russia as a relic of earlier times and Putin as a new tsar or a budding Stalin.

A reflection of the past? Many commentators and historians have seen direct continuities between today’s Russia and the Soviet and tsarist past. Credit: Artist KEMO; KEMO’s Gallery: https://kemo-caricature.blogspot.com/

As in the period of the Crimean War in the 19th century or the Cold War in the 20th, recent foreign policy conflicts between East and West have reinforced the notion that Russia is a simple throwback to earlier epochs. In 2014, US Secretary of State John Kerry called Russian aggression in Crimea a form of 19th-century behavior taking place in the 21st. President Obama, speaking in Estonia the same year, also referred to Russia as “reaching back to the days of the tsars—trying to reclaim lands ‘lost’ in the 19th century” (although, embarrassingly for the president’s speechwriter, imperial Russia lost no major lands, with the exception of the 1867 sale of Alaska).

Many observers immersed in Russian and Soviet history cannot help but perceive striking parallels between the dictatorial Russia being consolidated today and phenomena familiar from earlier historical periods. These go beyond the cult of the leader and extend to the prominence of powerful clans, rule through personal ties as opposed to institutions, glorification of the state, and corruption reminiscent of Gogol. Some historians have dusted off classic continuity theories in the field, seeking to establish perpetuations rather than breaks with the past. However, I would argue that the strong resurgence of the image of eternal Russia is misguided, in that it prevents us from thinking through significant breaks with the past.

The most famous continuity theory of them all is the late Edward Keenan’s “Muscovite Political Folkways,” a cult work among Keenan’s students at Harvard that was published in the Russian Review in 1986. One of the most cited and discussed articles ever published in the field, Keenan’s classic work posited “deep structures” of Russian history that were perpetuated by the unwritten, consensus-based “rules of the game” of a “political culture” stretching half a millennium after the rise of the Muscovite state.

There are a number of ways to think about continuity when considering Putin’s Russia that differ considerably from Keenan’s famous theory. For example, certain features of the tsarist old regime were perpetuated by historical actors operating on both sides of the Russian Revolution of 1917. Similarly, some attitudes and practices from the late Soviet era were carried over into the post-Soviet period by figures who gained in importance after the collapse of communism in 1991—most notably, by Putin himself. Russians’ own modern codifications or inventions of tradition themselves can also be seen as a kind of model for perpetuating the past. Rehabilitating previously discredited parts of Russian and Soviet history, including a growing fashion for justifying Stalin and Stalinism, is something actively going on in Russia today.

I would suggest, however, a different lens for evaluating continuities. Since the 1990s, historians have actively been debating the complicated question of Russian/Soviet modernity. While a number of historians object to how the “m-word” is notoriously hard to define, others reply that modernity is such a fundamental concept that it must be confronted. In Crossing Borders: Modernity, Ideology, and Culture in Russia and the Soviet Union (2015), I analyze these debates.

The question of Russian modernity is just as politicized as Russian backwardness. If one is a westernizing Russian liberal fighting the regime, for example, the anti-capitalist Soviet Union and the anti-Western Russian Federation are likely to be portrayed as not modern at all. By the same token, if an observer accepts the “West” as the gold standard for modernity, then the features Russia/USSR lacked, such as capitalism, the market, and civil society, become decisive. But many leading thinkers have argued that not all incarnations of the modern have been Western or liberal.

Crossing Borders argues for middle ground between the two poles of Russian/Soviet exceptionalism and a universally shared modernity. It develops the notion of a particular “intelligentsia-statist” modernity that spanned both sides of the Russian Revolution. At the heart of my discussion are cultural particularities that began in late imperial Russia and shaped the Soviet order—the bridge was that distinctively Russian group, the intelligentsia. This was an imagined community of intellectuals bound not by occupation or educational level, but a burning desire to serve (and lead) the people in order to transform Russia. During the uneven lurch to modernity under the tsarist autocracy, an intense intelligentsia crusade emerged to enlighten the masses and unify the cultural splits opened up by Russia’s Europeanization under Peter the Great.

Under tsarism the intelligentsia had little power to influence everyday life in the vast empire. Intellectuals and experts may have attempted to harness autocratic state power, but they were unable fully to do so. Only with the Bolshevik Revolution, whose leaders derived from the radical intelligentsia, was an anti-market, enlightenment crusade prosecuted with the full force of the revolutionary dictatorship.

Today’s Russia evokes simple continuities with the past for many observers. But the problem of continuities and change across political-ideological inversions presents perhaps the greatest challenge for all those who would use the Russian and Soviet past to understand the present day. In particular, the notion of intelligentsia-statist modernity leads to appreciation of some of the radical breaks between today’s Russia and the Russian-Soviet past. The strong state and its glorification, of course, remains; but the intelligentsia as a distinctive force shaping the country lies in the dustbin of history, at least for now. Russian authorities and the rest of the world—very unlike the many decades when communism became an alternative model and path of development—have little concern for Russian science, education, or contemporary culture. Today’s Russia looks back toward past glories, not to leaping over the most advanced countries into a utopian future. There are few if any domestic champions or foreign sympathizers for anything like an alternative “Russian model” of modernity. The more things change in Russia, the more they do not remain the same.

is professor in the School of Foreign Service and the Department of History at Georgetown University. He is founding and executive editor of Kritika: Exploration of Russian and Eurasian History and is author or editor of 12 books on Russian, Soviet, and transnational history.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.