Throughout our history, Americans have had conflicting attitudes toward alcohol. While one leading founder—George Washington—established a lucrative business distilling whiskey, another—Benjamin Rush, the nation’s most prominent doctor and a signer of the Declaration of Independence—devised a graphic “Moral and Physical Thermometer” to warn people of the dangers of drink. In the 19th century, many Americans embraced the temperance movement, while their compatriots in the liquor trade sought new markets for their products. The early 20th century brought Prohibition—and a concerted campaign against it. More recently, presidents have continued the long tradition of using toasting as a diplomatic tool, while Americans from First Lady Betty Ford to basketball star Shaquille O’Neal have continued the long tradition of cautioning people against the effects of imbibing.

The National Archives has recently opened an exhibit exploring this history. Spirited Republic: Alcohol in American History examines the production, distribution, consumption, and regulation of intoxicating beverages from the early years of the republic to today. On view through January 10, 2016, in the Lawrence F. O’Brien Gallery of the National Archives Museum in Washington, DC, the exhibit captures Americans’ varied views about alcohol and the government’s changing policies toward it.

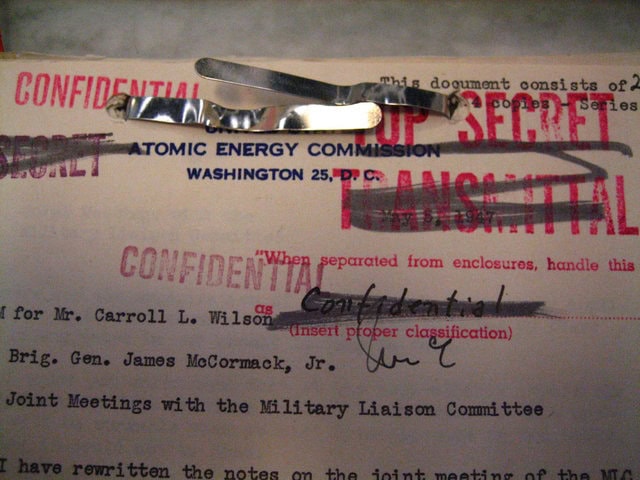

A pro-Prohibition booth at the Parents’ Exposition at the Grand Central Palace, New York, New York, March 1929. National Archives, Records of the Internal Revenue Service

The exhibit is divided into four sections that examine drink in American history thematically and chronologically. “Good Creature of God” focuses on the early republic and the later part of the 19th century. Here the story is that beer, cider, perry, wine, and spirituous liquors were long accepted parts of everyday life. Images show how quaffing liquor was woven into the rhythms of the day, and a striking display of gallon jugs depicting alcohol consumption throughout US history shows just how much booze Americans put away in different eras. Highlighting the place of alcohol in American economic history, this section also includes a reproduction of George Washington’s still, along with letters from merchants seeking to sell their goods to consumers in distant parts. Late 19th-century traders, the documents reveal, hoped to find markets in faraway places including Muscat, Oman, and German Samoa.

As the tower of jugs in the first section shows, Americans’ consumption of alcohol spiked dramatically over the early decades of the 19th century as the agricultural exploitation of lands in new western territories and improvements in transportation made shipping corn in the form of whiskey highly profitable. Reformers responded by “Demonizing Drink,” as the second section explores. Even before an organized movement emerged, some activists—most notably Benjamin Rush—sought to curb Americans’ (and even foreigners’) drinking. A blow-up of Rush’s “Moral and Physical Thermometer,” positioned to move the viewer from the first to the second section of the exhibit, makes that point and shows that moderation was the focus of early temperance advocates. Over the next decades, reformers developed a sophisticated movement to lessen Americans’ drinking. Along with a Women’s Christian Temperance Union picture of women praying in a saloon and a poster advertising a temperance lecture, an 11-foot-long petition from 1843 calling for an end to the Navy’s “spirit ration” showcases the movement’s popularity. In spite of its success—by the latter 19th century, as the tower of jugs shows, drinking the hard stuff had fallen markedly—many Americans supported a legal ban on the production and sale of alcohol. “Demonizing Drink” examines the evolution of the temperance movement into prohibition. The medical profession, the exhibit shows with material such as a page from the patients’ register at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, DC, contributed to this development by shaping the public’s ideas about alcoholism as an illness. By 1919, the prohibition movement had become so strong that states passed and Congress ratified the 18th Amendment. A highlight of the exhibit is the original Joint Resolution for the 18th Amendment, on display for the exhibit’s first six months.

An automobile decked out with signs and banners supporting the repeal of the 18th Amendment, New York, New York, May 1932. National Archives, Records of the US Information Agency

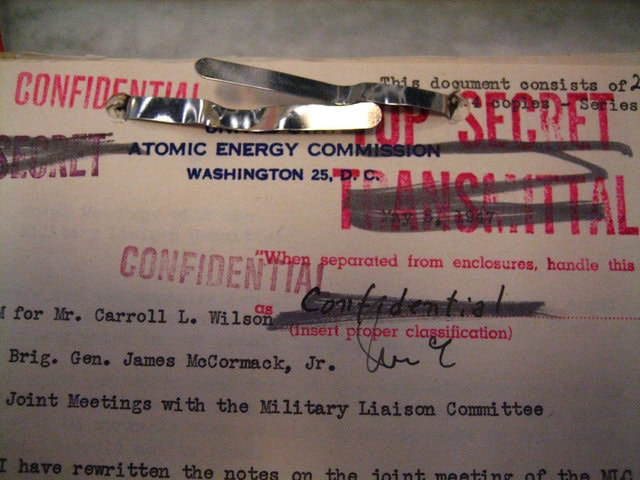

Not everyone, however, supported the anti-drink cause. The exhibit’s “Sober Nation” section captures the conflict over the nation’s experiment with Prohibition. Agents, male and female, worked to enforce the law—agents’ badges are on display and photos show some of them dismantling an illicit bar—and supporters of the movement kept the pressure up. Many Americans bent or flouted the law, and the exhibit includes doctors’ prescriptions for hard liquor as well as materials relating to the era’s organized crime in alcohol. Arguing, among other things, that Prohibition was unenforceable, opponents of the 18th Amendment crafted a repeal movement. Pro- and anti-Prohibition camps shared some similarities; both, for instance, appealed to the well-being of families, as photographs and posters on view reveal.

When the 21st Amendment went into effect in 1933, the nation saw the repeal of Prohibition. The exhibit’s final section, “Concerned Acceptance,” covers this history and brings the story up to today. Many Americans celebrated repeal, as film and photographs from 1933 show, while wine, beer, and spirits makers offered the public both old and new products. One of the exhibit’s most colorful displays is the collection of 39 labels—in various languages—for different wines, beers, and spirits submitted to the Patent and Trademark Office as the American liquor industry geared up for the return to licit alcohol sales. Legal again, drinking still prompted concern. Americans came together in new groups, such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving, and mounted yet new reform campaigns. Documents, posters, and film clips show ordinary people and well-known figures counseling responsible drinking and offering encouragement to those coping with alcohol-related diseases. The exhibit closes with displays including FDR’s cocktail set and drink-related gifts other presidents received.

With issues around taxation and the military also running through the exhibit, Spirited Republic conveys not only the contested but also the multifaceted role of alcohol in American history.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.