This past weekend, I attended the Society for Military History annual meeting in Montgomery, Alabama. Though it’s true that everything—and everywhere—has a history,

it’s also true that some places are more drenched in history than others. Some cities, it seems, have more than their fair share of important historical events, showcased by historical markers on every corner and an abundance of museums or buildings under preservation. Maybe it’s just me, but I get a special thrill when I know I’m in an especially historic city. A few summers ago I was in Berlin, and the whole city seemed to flirt with me, the trees and buildings and cobblestones tempting me with their hidden (or not so hidden) histories. Similar uncanny sensations followed me around a past SMH meeting in New Orleans, where the past and the present coincide in ways that make one inclined to agree with William Faulkner: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” And I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that the AHA’s next annual meeting will be in Atlanta, a city with its own diverse and rich history.

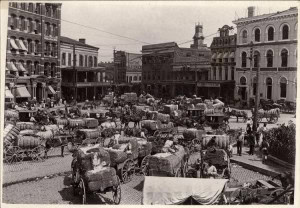

Montgomery is likewise one of those cities that seem super-saturated in history. Walking to the local drug store (am I the only one who inevitably forgets something essential, like a toothbrush?), I passed the Court Square fountain, which is built near both the site of a former slave auction and the Winter Building, which once housed the telegraph used to authorize General Beauregard to fire on Fort Sumter, thus igniting the Civil War. I later passed a historic marker by the bus stop where Rosa Parks famously alighted and refused to stand up. (As far as I could tell, it was no longer a working bus stop. April’s Perspectives contains an article on Rosa Parks’s contested legacy.) On my way to the opening reception, I walked down historic Dexter Avenue, towards the state capitol building—the destination of the Selma to Montgomery march that is celebrating its 50th anniversary, and the subject of a conversation-generating film.

I know I was not the only one who noticed my rich historical surroundings. I overheard a few conversations in elevators and during breakfast, and I even chatted with fellow attendees about it at receptions. All of us military historians were as buzzed about the history around us as the history we were discussing at panels—and there was some very interesting history being discussed. The panel I chaired, “Britain Stands Alone: Reassessing 1940,” attracted a standing-room-only crowd. Two other sessions I attended, “The Many Spoils of War: The Impact of Gender and Sexuality on Twentieth Century American Conflicts Abroad” and “New Approaches to the History of Military Veterans in the Twentieth-Century United States,” offered chances to trace the impact of the US military at home and abroad over a broad expanse of time. And as always, the exhibit hall featured a wide array of new scholarship in military history. Indeed, surveying the panels on the program and publishers’ displays of new books, one might be struck by the way war and its aftermath has affected nearly every time period and geographical region. Military history, though it often has its own distinct point of view, can very often offer an entryway into many other historical questions—an argument the SMH made in a recently published white paper.

As I made my way through the conference, however, I found myself thinking about the many ways historians practice their craft, and the false divisions that are sometimes erected between subfields. The AHA currently has over 100 affiliated societies, and some might see such a proliferation of topics and temporalities as diluting the discipline. Rather, such a diverse yet interconnected web of knowledge is one of the strengths of historical inquiry; indeed, it is fundamental to the discipline. In a city where multiple histories from different times and cultures seemed to layer on top of each other, I was reminded of the usefulness of all histories and how they build upon each other. Perhaps R. G. Collingwood was right when he wrote that the past is like an onion with many layers to be uncovered, and perhaps it is our job as (historians of all topics) to put the layers back together—turning disparate events into a coherent story.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.