Imagine yourself as a child. At the age of 12 or 13, how well would you have been able to articulate your daily experiences—at home, at school, walking down the street—as they relate to your country’s history and politics? Though some of us may have understood ourselves as historically situated subjects more clearly than others at that age, we would still have critical gaps in our perception. And if our lives depended on our ability to perform this analysis in a court of law, we would need help.

Students in 2019 work together in the Immigrant Justice Lab to draft legal briefs rooted in immigration history, in consultation with faculty and attorneys. Gregory Parker/University of Michigan Department of History

Unaccompanied migrant children seeking asylum in the United States need precisely this help. To obtain asylum, they must show US Citizenship and Immigration Services that they have a credible fear of persecution in their home country on the basis of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. Immigration attorneys provide this help for free to children referred to them by the Office of Refugee Resettlement. In recent years, however, their efforts have been spread thin as more children seek asylum than ever before.

The University of Michigan’s Immigrant Justice Lab represents one local effort to improve the quantity and quality of resources available to unaccompanied migrant children and their attorneys. Co-founded in 2018 by Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof, professor of history and American culture, and Rebeca Ontiveros-Chávez, supervising attorney at the Michigan Immigrant Rights Center (MIRC), the lab conducts research to support children’s asylum claims. “The initial idea was simple,” Hoffnung-Garskof explained. “Rebeca and her colleagues at MIRC had an exploding caseload. My undergraduate history students had a wide array of skills that were a good match for some of the areas MIRC needed the most help—finding out about local conditions in the societies that asylum seekers had fled. We decided to experiment with workshops and seminars designed around teaching students to do this work.” Piloted as an end-of-semester project in Hoffnung-Garskof’s undergraduate Immigration Law course, the Immigrant Justice Lab is now a stand-alone course that offers undergraduate history students and law students the chance to partner with immigration attorneys on complex cases. “The lab always borrowed from the model of clinical instruction, and there are tasks involved in this work that even the best undergraduates cannot learn to do in a semester,” Hoffnung-Garskof said, “so bringing students and instructors from the Law School into the project made sense. We were lucky to recruit Amy Sankaran and Jessica Lefort, law faculty who value interdisciplinary work and who see the value that our undergraduate students bring to the project.”

The Immigrant Justice Lab asks students to consider how history shapes people’s lives in the present. As the Immigrant Justice Lab coordinator over the last nine semesters, I have helped students collect and interpret evidence that connects children’s personal stories to their political, historical, and cultural contexts. For example, when a child from El Salvador flees to the United States to escape abuse at home, students must show how institutions like family, medicine, and the law have been destabilized over time by the Salvadoran Civil War (1979–92), displacement, and the rise of gangs. These historical factors increase children’s vulnerability by normalizing certain kinds of violence, isolating them from extended family, making authorities reluctant to intervene for fear of gang retaliation, and forcing victims to navigate a legal system that is at best inefficient (and at worst corrupt). Mechanisms for international protection kick in when states are unwilling or unable to protect children from private-actor violence.

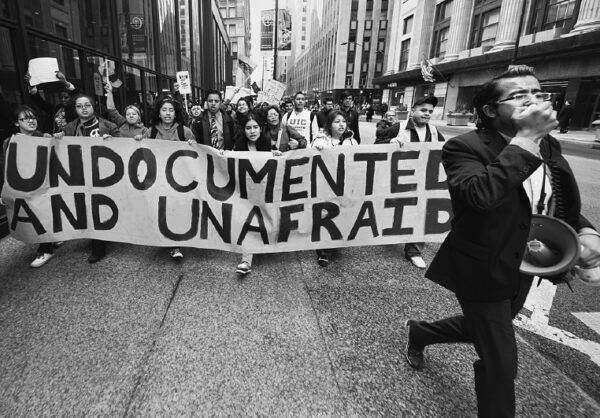

Students learn about the factors that drive many migrants to seek asylum in the United States.

Students also learn how the history of US immigration law shapes children’s experiences of the asylum application process. The criteria used to define a refugee in immigration law emerged in the aftermath of World War II, opening a small escape hatch for displaced European Jews and political dissenters fleeing communist states without fundamentally challenging the restrictive quotas created to curb European immigration in the 1920s. That definition maps imperfectly onto unaccompanied migrant children, as most are displaced not by state-sanctioned genocide or political activism but by a lack of protection from gangs and domestic violence. Children must demonstrate their asylum eligibility by satisfying narrow and exacting legal tests intended to show that their experiences are analogous to those for whom the term refugee was created. Drafting a brief for such a case can feel like cutting a key to fit a lock not designed to open it. “Our current realities of the immigration system are a direct result of this country’s history of exclusive nationalism,” said Carolyn Chen, a current research assistant and recent graduate. “From the very first immigration exclusion acts in the 19th century, we’re able to see how those in power can use the idea of borders and exclusion to maintain their position. Through the lab, we’re exposed to the tangible ways our nation’s history still impacts people today.”

By conducting research for asylum briefs, students learn about the factors that drive many migrants to seek asylum in the United States. As they research the histories of the children’s countries of origin, they can see the impact of US immigration law and policy on a global scale and comprehend how the histories of the United States and other countries are intertwined, giving them particular insight into these cases. “The hands-on experience is crucial to promoting cultural competency,” said Yezeñia Sandoval, a former lab student. In her view, class discussions became more “productive and informed” after she and her peers were able to see immigration law from the perspectives of refugee children.

Students know the stakes are high. Chen said that her research team “spent hours together reading our briefs line by line,” anxious to perfect every detail. Students receive guidance and feedback directly from immigration attorneys on their briefs, and every draft undergoes a round of peer review by classmates. The political and legal landscape of immigration law shifts rapidly, however—deadlines can change on short notice, and sometimes students need to change strategies even after putting significant time and effort into a brief. Even though attorneys request help with cases long before they are due to US Citizenship and Immigration Services, they cannot predict sudden changes to immigration law. Students therefore must adapt under pressure. Former student Isabel Zuñiga emphasized that this work “required passion as well as flexibility.” Although dealing with such rapid changes could be frustrating, Sandoval said it also made her “more aware of political movements and actors tied to the immigration system’s evolving nature.”

Despite the harried pace at which students work, it may be years before an immigration judge decides the outcome of a case. Nicole Tsuno helped draft nine asylum briefs during her two and a half years in the lab but only knows the outcome of one. The brief, written for a 15-year-old girl, succeeded in a court with some of the country’s highest denial rates. While students count such successful cases as victories, they know that sharing the most traumatic experiences of their lives and then waiting years for relief can be extremely difficult for children. “Our clients are traumatized and dealing with a retraumatizing immigration system,” Tsuno said. “I am lucky to never have to go through that.”

One challenge of a partnership between a busy legal aid agency and a university is the way time is organized differently in each domain. Major changes to the asylum application process are often announced in July and December, when students are on break or preparing for exams. The lab therefore retains students as research assistants during summers and holiday breaks. Keeping the lab running year-round is crucial for maintaining strong relationships with immigration attorneys. These students also perform tasks critical to the lab’s functioning, such as maintaining its national research database for immigration lawyers.

The database is the brainchild of Ontiveros-Chávez and two former students in the lab, Meghan Brody and Elijah Aarons. Ontiveros-Chávez wanted to create a system for immigration attorneys to share resources they could use to build cases for clients. Together, Brody and Aarons—undergraduate majors in library science and computer science, respectively—designed and built a database to accomplish that goal. While Aarons worked on the coding, Brody focused on user experience: designing the database interface; conducting user testing; and collecting, organizing, and maintaining data. “It’s so exciting to see how the project that I was part of building has grown into something that’s helping so many people,” Brody said. She credits the lab with giving her skills she now uses as a user experience specialist and database system administrator at a public library.

Community-based learning means that students aren’t learning about history in a vacuum.

Other students in the lab have gone on to pursue law school or to work in immigration law and public policy, and even with the United Nations. After graduating, Sandoval landed a job at an immigration law firm in Chicago. “Due to my experience in the lab, I was able to apply critical thinking skills and direct knowledge of immigration law to help clients navigate the complicated and oftentimes lengthy visa application process,” she said. Both Chen and Zuñiga are pursuing law degrees with the goal of becoming immigration attorneys. “The experience of working with MIRC attorneys was crucial in shaping my career aspirations,” said Chen.

Understandably, instructors might hesitate to propose and develop community-based learning projects like the Immigrant Justice Lab because of the increasingly antagonistic political climate toward teaching students about racism in US history. Students in the lab, however, view the passage of laws against divisive concepts critically. “Racial division is what happens when we don’t encourage community-based learning projects,” said Tsuno. Grounding discussions of immigration law in the experiences of unaccompanied children and in history combats simplistic narratives and racist stereotypes about immigrants, creating a “controlled, informed environment” for students to discuss immigration issues, added Zuñiga.

Community-based learning means that students aren’t learning about history in a vacuum. “By learning how to tell complex stories of migration within the constraints of the asylum system, students gain a clearer view of the history of how humanitarianism overlays contemporary immigration politics, and the lives of contemporary immigrants,” said Hoffnung-Garskof. “Every history major has heard the question, ‘History—what are you going to do with that?’ Our students may not know what they will do in the future, but they are already doing things with history.”

Grace Argo is a PhD candidate in history and women's studies at the University of Michigan.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.