After Adam Goodman (Univ. of Illinois at Chicago) finished his bachelor’s degree, he spent five years guiding students from underrepresented populations through the college admissions process, as well as teaching high school history on the United States–Mexico border, before starting a graduate program in history.

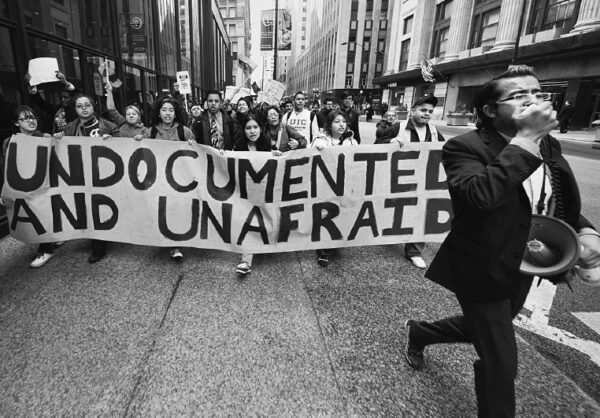

Protesters march through Chicago in 2010 during a “Coming Out of the Shadows” rally. Peter Holderness

Once there, Goodman thought he might “pursue questions related to social policy and educational inequality, which,” as he told Perspectives, “I had studied and worked on in the past. But I became more and more drawn to immigration history and policy.” His work as a college recruiter and high school teacher meant seeing, up close, how immigration policies affected people’s lives on a daily basis and led him to the subject of his first book, The Deportation Machine: America’s Long History of Expelling Immigrants (Princeton Univ. Press).

In it, Goodman traces the long history of expulsion and, as he writes, “exposes the various ways immigration authorities have forced, coerced, and scared people into leaving the United States from the late nineteenth century to the present.” The groundwork for the modern deportation machine came out of the anti-Chinese campaigns of the late 19th century, when the Gold Rush and transcontinental railroad increased demand for cheap labor. As early as 1830, writes Goodman, the popular press reflected anxieties about this new influx of immigrants being an unassimilable existential threat to white America. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 allowed the federal government to deport “any Chinese person found unlawfully within the United States,” and the 1885 Foran Act prohibited, as Goodman phrases it, “the importation of ‘alien contract labor,’ irrespective of country of origin.” Following this formal governmental intervention, many communities— particularly in the West—began informal “Chinese expulsion and self-deportation campaigns, relying on a combination of force and coercion.” Though Asian immigrants were not the only ethnic group targeted by American nativist movements of the 19th century, the concerted efforts to force them out, by both public officials and private citizens, are a recognizable starting point for what Goodman identifies as the three primary mechanisms for expelling immigrants from the US: formal deportations, voluntary departures, and self-deportation campaigns.

Formal deportations are the most visible. They make the news and also comprise the bulk of scholarly research on this topic. However, as Goodman writes, “more than 90 percent of all expulsions throughout US history” have been through the euphemistically named “voluntary departure” and the equally euphemistic “self-deportation.” Voluntary departures result when immigration officials coerce arrested immigrants to leave the country before the process of a formal deportation trial. According to Goodman, voluntary departure “has inextricable connections to the history of large-scale Mexican migration to the United States” after the Mexican-American War of 1846–48 and especially after the 1907 Gentleman’s Agreement between the US and Japan, which “put an end to significant labor migration from Asia.” Mexican and, later, South American labor became an often-exploited fixture in the US market. As labor rights movements gained prominence, one popular way to keep workers from unionizing was to have protesters or pro-union workers arrested, at which point immigration officials would convince them to leave the US rather than go to prison or to trial.

How do you write a history that has been deliberately obfuscated and erased?

“Self-deportation” refers to immigrants leaving as a result of social pressures, threats, concerted fear campaigns, boycotts, and violence by private citizens. A good example of this is, in the late 19th century, the public reaction to the threat of “Yellow Peril,” in which private citizens created such an atmosphere of tension, distrust, and danger that workers were “warned out” of the United States and left the country without governmental intervention. However, these two “soft-power deportation mechanisms,” as Goodman phrased it in a conversation with Perspectives, “were not meant to be tracked” and were “meant to leave no trace as a cost-saving measure.”

These events pose a difficult question: How do you write a history that has been deliberately obfuscated and erased? When he was a third-year graduate student, Goodman says, “a senior scholar more or less [told] me that writing this history that I was proposing could not be done.” His first research visit to the Historical Research Branch of the Department of Homeland Security’s US Citizenship and Immigration Services was likewise discouraging. As he writes in the book, “despite the wealth of materials documenting the immigration service’s history, there were no records on voluntary departures, much less on self-deportations,” and “the available federal immigration records at the National Archives only cover the period up to March 1957.”

Goodman’s search was complicated further by the fact that immigration history is, by definition, not confined to one specific place. He had to dive into archives scattered across the US and Mexico, often finding sources in obscure folders that didn’t seem to have anything to do with voluntary departure or self-deportation. (“For historians, archivists, librarians, and institutional historians certainly are our best friends,” Goodman says, crediting them for “invaluable assistance” over the 10-year course of the project.) He found other sources in a variety of unexpected places, including a storage unit in downtown Los Angeles, the office of a Boston legal aid organization, an unmarked warehouse in Mexico City, and the National Border Patrol Museum in El Paso, Texas.

Goodman’s experiences outside academia once again proved useful when he exhausted the archival sources. His experience as a freelance journalist for popular publications provided a skill set that not only helped him to track down every possible lead, but also to not get discouraged when the first approach didn’t pan out. “I learned to grow a thick skin very quickly,” Goodman told Perspectives. “I learned not to take ‘no’ for an answer. I accepted that people would turn me down, but I would just go to the next lead and the next possibility.”

Goodman’s experiences outside academia once again proved useful when he exhausted the archival sources.

Goodman also put his journalistic skills to use by conducting a number of oral histories. “I spoke with more than thirty people, conducting in-depth oral histories in Chicago, Texas, California, and different parts of Mexico,” he says. “In addition to migrants and their family members, I spoke to union organizers, immigration lawyers, some immigration officials, and statisticians.” These interviews were vital, as many migrants’ experiences not only supplemented what Goodman had found in institutional records in traditional archives, but also provided entirely new information and new perspectives on well-known incidents and events. “Oral history provided another way to shed light on some of those experiences and to better understand how deportation affected people’s lives from their perspective.”

Though the book is focused on the state mechanisms used to force recent arrivals out of the US, Goodman takes pains to show, as he phrased it to Perspectives, “how people have fought back by identifying the machine’s weak points and pressing on them.” One of Goodman’s most surprising discoveries in the course of his research was “the ingenious strategies that people developed and relied on to protest deportation. Just remaining silent and keeping your mouth shut became the best way to avoid deportation. Before databases were integrated and connected, there was no way for immigration officials to prove where someone was from, if they didn’t tell them where they were born and their country of citizenship.” Goodman also traces the rise of resistance to mass expulsion, with particular focus on grassroots organizations in the 1970s such as the Center for Autonomous Social Action–General Brotherhood of Workers (CASA), and ending with the current “mass solidarity movement” in which immigrants and their allies “have taken to the streets, filed lawsuits, descended on airports to protest the Muslim ban, organized ‘Know Your Rights’ workshops and anti-deportation trainings, and pushed religious institutions, towns, and cities to declare themselves sanctuaries for undocumented people.”

Though the 2016 election both complicated Goodman’s work and spurred him on to finish the book, it also provided him with a different project in the field of immigration studies. At the 2016 Social Science History Association in Chicago, Goodman and other colleagues began “discussing ways in which we might be able to contribute to public discussions and further public understanding of immigration history, at a time when the newly elected president had been doubling down and hammering home anti-immigrant rhetoric and the demonization of foreigners.” The resulting project is the #ImmigrationSyllabus, a 15-week course, featuring mostly publicly available online resources, that provides historical context for current debates over immigration, as well as bringing together key texts that helped shape the field. Goodman recommends it for those unfamiliar with immigration studies or seeking a way to teach this important contemporary issue in historical context, “with the one caveat that it only goes up until January 2017, and a lot of really excellent work has come out in the last two years that we weren’t able to include.” Goodman says, “There are important debates to be had around these questions, and the immigration syllabus would be an excellent place for people to start,” particularly the ongoing debate on whether the United States is “a nation of immigrants or, perhaps, a deportation nation.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.