On April 1, 1980, Hector Sanyustiz and four others, seeking political asylum, slammed a bus into the gates of the Peruvian Embassy in Havana, Cuba. Their actions precipitated what José Manuel García, associate professor of Spanish and Latin American studies at Florida Southern College, calls “one of the largest exoduses in modern history.” During the Mariel boatlift, over 125,000 Cuban citizens, disillusioned with life under Castro, boarded boats at the port of Mariel to emigrate to the United States. The six-month period, which rocked both Cuba and the United States, is the subject of García’s new book, Voices from Mariel: Oral Histories of the 1980 Cuban Boatlift (Univ. Press of Florida).

José Manuel García, accompanied by a documentary filmmaking team, gets ready to enter the home he left in Cuba in 1980. José Manuel García/NFocus

The work contains a comprehensive collection of witness testimonies of the event, including one from García himself. A “Marielito,” García fled Cuba with his family at the age of 13 and recalls traumatic memories of escaping the port and eventually settling in New Jersey. The book opens with a brief account of the events that led to the boatlift: following Sanyustiz’s actions, tens of thousands of Cuban political dissidents, fed up with food shortages, propaganda, and persecution, started camping out on the grounds of the Peruvian Embassy seeking asylum. In a surprise move, Castro decided to relieve the crisis by announcing that any Cuban who wanted to leave the island could do so; the announcement rippled through the country and outward, causing chaos.

“I wanted to show how the Marielitos are a diverse group of people from various social, religious, and professional backgrounds.”

Almost immediately, the turbulent Florida Straits swelled with rafts and boats carrying refugees to Key West. As they waited for their chance to earn a spot on a departing boat, García’s family feared actos de repudio, or mob attacks, from their pro-Communist neighbors. The first boat the family boarded started taking water almost immediately after launch. Rescued by a neighboring shrimp boat also on its way to Florida, the family soon found itself crowded together with 200 other people in squalid conditions. In Voices from Mariel, García remembers that “it was impossible to sleep as everyone had to urinate and vomit in place.” Just as the passengers lost all hope of survival, the bright lights of a US Coast Guard boat appeared in the distance. “It was the realization of a dream I had envisioned for as long as I could remember,” García recalls in the book.

García could not speak English when he first arrived in the United States, but like many other Marielitos, he eventually assimilated into American society, earning a PhD in Latin American literature from the University of Arizona. With each passing year, and with tensions between the United States and Cuba showing no signs of easing, the possibility of ever returning to his homeland faded. In 2008, García was granted a semester-long sabbatical from Florida Southern to pursue what he thought was a strictly academic interest in the Mariel story.

From the beginning, García writes in Voices from Mariel, he felt compelled to do more than tell the story of the boatlift: “I needed to shed some light on the Marielitos themselves. I wanted to show how the Marielitos are a diverse group of people from various social, religious, and professional backgrounds.” From Castro’s point of view, the departing refugees—many of whom were highly educated political prisoners, queer people, or petty criminals—were simply escoria, or the “filth of society.” Unfortunately, Americans did not hold a nuanced view of the new arrivals either. The US media publicized instances of Cuban American crime and sensationalized the notion that undesirable persons were pouring into the streets. In the classic 1983 film Scarface, for example, Al Pacino plays a Mariel refugee who becomes a ruthless drug lord. Such characterizations helped perpetuate stereotypes that Marielitos are still struggling to overcome.

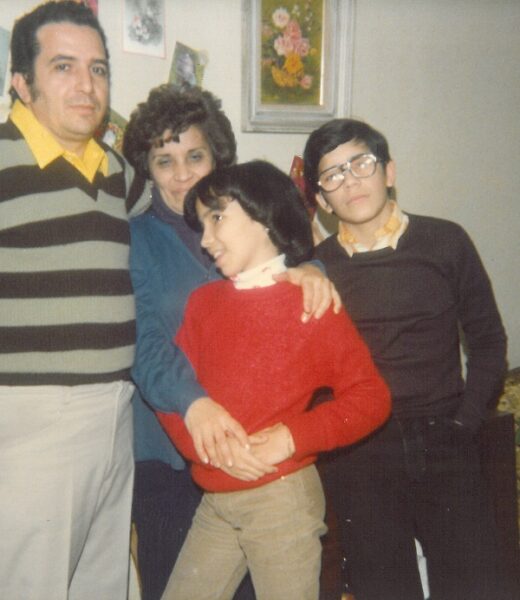

José Manuel García (right), age 13, and his family arrived in New York City a few days after leaving Cuba. Courtesy José Manuel García

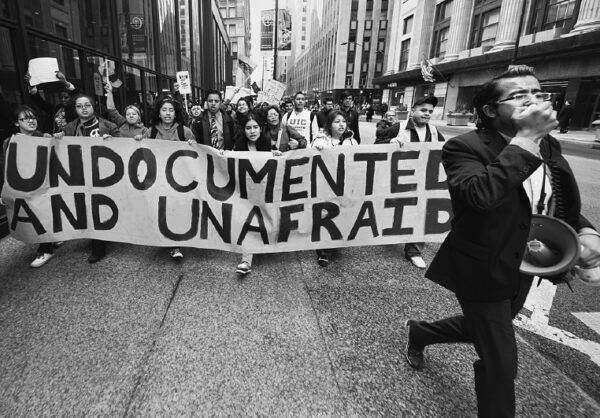

Upon returning to his classroom, García shared some of his preliminary interviews with Marielitos with his students. Startled by how captivated they were by the stories, García admitted that he had a long-buried urge to revisit Cuba. The turning point for García came when one of his students, Jesse Larson, offered to put him in touch with a film production company called NFocus. “To make a long story short, they were just as excited as I was about doing a documentary on the Mariel boatlift and capturing my return,” García told Perspectives. NFocus helped the scholar raise funds to conduct more interviews and undertake a risky journey back to Cuba—a country he wasn’t so sure had forgiven him—to face the ghosts of his past. “The book sort of went on the back burner for a while,” admits García. The documentary, also called Voices from Mariel, was released in 2011 to a warm reception, earning several film festival awards and broadcast space on the Spanish-language TV network Nat Geo Mundo.

Still, García was very conscious of the need to give the film a written counterpart. “There are a lot of histories done on the boatlift’s effect on the labor market, and a few on sociology,” says García, but there are not very many witness accounts. The documentary also helped García pitch the book to editorial board members at the University Press of Florida—they believed having the film as an accompaniment would enhance the book’s popularity as a teaching tool. Seven years later, oral interviews that were otherwise clipped or abridged in the documentary appear in full in the text. “The book is designed to provide a more comprehensive and detailed account of witnesses’ experiences presented in the documentary,” explains García.

When gathering interviews for Voices from Mariel, García had to both teach himself the best practices of oral history and make special considerations for the needs of subjects. “One of the things that I encountered during the interview process was that Cuban Americans tend to ‘get away’ from the past. Sometimes I had to bring them back,” he says. Nevertheless, García found that testimonies were surprisingly consistent, particularly in describing the atmosphere at the Peruvian Embassy, tensions in communities as families awaited clearance from the Cuban government to emigrate, and the emotional experience of crossing the Florida Straits. “Unless they were going far away from the story line,” says García, “I would let them talk.”

From Castro’s point of view, the departing refugees were simply escoria, or the “filth of society.”

Five of the interviews that García originally conducted do not appear in the book or documentary because he deemed them too historically unsound to publish. He tells Perspectives, “The last thing I wanted to do is put something out there that they’re going to question me on later.” His own position as both subject and scholar further helped him evaluate the testimonies. “I think that the fact that I was part of that event made a difference,” he says. “I could tell when someone was being hyperbolic or saying something that I didn’t think was right. I called them on it, I questioned them. I feel that what I put out there is as precise as what it could have been in terms of the experiences and the testimonies of what people lived.”

García has already received calls from viewers who remember his documentary and are eagerly anticipating the book. He is cognizant that recent events, such as the thawing of diplomatic relations between Cuba and the United States, have increased public attention on Cuba. “It’s not like I planned it, but the topic is perfect,” he muses. García has also noticed a lot of interest about the Mariel boatlift from reporters in countries facing immigration-related issues. A writer from Germany’s Mare magazine, for example, recently got in touch with him for an editorial feature on Mariel meant to assuage fears about the country’s burgeoning refugee crisis. García explains, “One of the points [the writer] wants to make is that the negative image that was attached to the Mariel boatlift refugees over time was proven to be wrong. Over half of the Mariel boatlift refugees have made it into the middle class. The percentage of criminals was very minimal—most of this was propaganda from both the US and Cuban governments.”

García strongly feels it part of his personal mission to correct American and Cuban misconceptions about the boatlift. If you ask ordinary Cubans how many left the country during the boatlift, García notes, many will say, “oh, only about three or four thousand.” The actual number is closer to 125,000. At a time when so many people are paying attention to Cuba, García hopes that he can provide both personal and professional guidance to challenge ingrained perceptions about the boatlift. “This project has connected my academic interests with my personal reality as a Mariel refugee,” he says. “It really gives a lot more meaning to my role as an educator. . . . I hope that one of the things I am providing is changing that negative image of refugees that they were all criminals.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.