The United States and North Korea recently exchanged several hostile and absurd words—“enveloping fire” (North Korea), “we are now a hyper power” (US), and, of course, “fire and fury” (POTUS). This is not the first time that the two countries have engaged in incendiary rhetoric since the Korean War ended in 1953. While another war has not happened—and a war today is very unlikely—the ongoing “war of words” has helped build the military cultures and economies of the two countries. In fact, the recent rhetoric overshadows the continuous growth of the two militaries and restricts possible avenues of constructive dialogue between the governments, public and private organizations, and communities in the two countries.

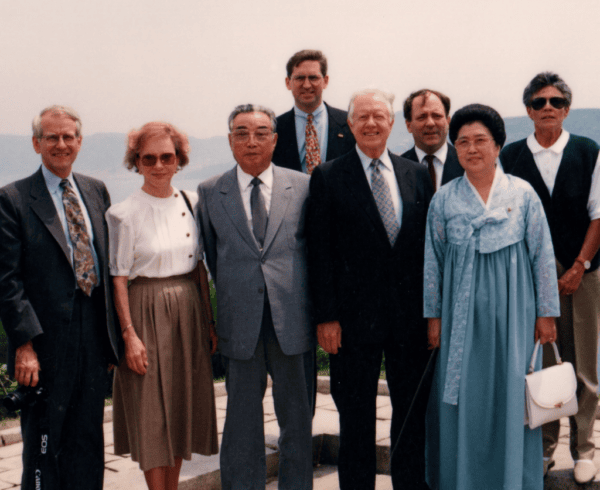

President Jimmy Carter with Kim Il Sung, the leader of North Korea, in Pyongyang in 1994. During his trip, Carter negotiated a freeze on North Korea’s nuclear program. Eason Jordan

A look at Rodong Sinmun, North Korea’s party newspaper, can tell us, for example, what the country was saying about the global nuclear threat of 1962, which culminated in the Cuban Missile Crisis in October. What drew my attention in particular was the reporting on US military’s actions in the months prior to the Cuba events. On October 17, North Korea protested against the latest deployment of weapons—including Sidewinders, M47 and M48 tanks, and the new Lacrosse missiles capable of carrying nuclear warheads—to South Korea by the US military. This shipment of arsenal to South Korea was connected to the Cuban Missile Crisis. It was part of the US’s global readjustment of its nuclear weapons against the Soviet Union and its allies, which in turn prompted the Soviet Union to readjust its own nuclear weapons against the US by way of Cuba. The US’s positioning of nuclear capable Jupiter missiles in Italy and Turkey in 1959 was the most serious matter, but what was happening on the Korean peninsula was also significant. That autumn of 1962, Rodong Sinmun described the United States as “lunatic American imperialists . . . dragging their murderous weapons all over the place.”

An exchange of words similar to today occurred three decades later in June 1994 when North Korea began processing nuclear fuel rods to make plutonium and warned the world that it was going to withdraw from the Non-Proliferation Treaty. North Korea claimed that its actions were in response to the growing threat of nuclear war on the Korean peninsula initiated by the United States. The two countries seemed ready for war that early summer. The Washington Post carried an op-ed with the title “Korea: Time for Action,” in which the authors warned Korea that a war would “result in total defeat of North Korea and the demise of the Kim Il Sung regime.” At the same time, Rodong Sinmun portrayed the United States as a “grave threat to the peace of the Korean peninsula.” The brinkmanship subsided when Jimmy Carter went to Pyongyang and negotiated a freeze on the nuclear program with Kim Il Sung (one reason Carter won the Nobel).

The United States and North Korea have been exchanging confrontational rhetoric over the issue of nuclear missiles for over 50 years. That not a single nuclear weapon has been launched, despite some tense moments, suggests that some kind of rationality is operating on both sides. North Korea’s pursuit of the nuclear program for energy and weaponry, which began in late 1950s, too, is a rational choice in the face of decreasing GDP, trade, and foreign aid and increasing international hostility and isolation as its state socialist allies dissolved in early 1990s.

Getting back to the headlines, the “battle of rhetoric” is never just about words. Since the end of the Korean War, a yearly number of around 35,000 US military personnel in 83 military sites have made permanent marks on South Korea’s geography, culture, and economy. North Korea has created the fourth largest army in the world, with a million soldiers. The demilitarized zone stretching across the Korean peninsula is station to hundreds of thousands of US, South Korean, and North Korean soldiers ready to go to war. The two countries’ military spending has been an object of criticism, and rightfully so. The US military budget for 2018 is 800 billion dollars, which is more than half of the entire government budget (and more than one third of world military spending). North Korea’s military budget is outrageous as a percentage of its GDP—more than 20 percent (around 3.5 billion dollars). On top of all this, militaries in the two countries are supported by research, publicity, education, private ventures, and cultural and social discourse. A war of words, thus, continues to shape people, organize ideas, support the building of weapons and infrastructure, and ultimately legitimize the very existence of militaries. A war with North Korea is improbable, but as long as a war of words continues, the militaries of the two countries will certainly maintain their course.

In the current moment, Americans are once again being made aware that, in the age of nuclear weapons, no country is safe. The tautology here is that this condition was created, and thus it can be dismantled. Such a position is about having a clear awareness of our impermanent, historical condition, a healthy sense of mortality, if you will. In 1964, Robert Oppenheimer spoke at UCLA about his fellow physicist Niels Bohr. Bohr, who died in 1962, had been, like Oppenheimer, a strong advocate for international control of nuclear weapons. In the lecture, Oppenheimer expressed his admiration for Bohr’s “deep appreciation of mortality—mortality that screens out the mistakes, failures, and follies that would otherwise encumber our future, [mortality] that makes it possible what we have learned and what’s proved itself be transmitted for the next generation.” From such a position, thinking like the military is not all that useful even though we constantly do so (Will the North Koreans attack? Will China join them? Will the US bomb Pyongyang?)—enough money, personnel, and infrastructure are devoted to that. More useful when it comes to the issue of North Korea would be to think like communities, in terms of dialog, history, and empathy for other fellow human beings—that is, in terms of our mortality.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

C. Harrison Kim is assistant professor in the Department of History at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa. His book The Furnace is Breathing: Work as Life in Postwar North Korea is forthcoming from Columbia University Press.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.