Italian immigrant Sebastiano Salafia was arrested for throwing rocks at the police during the 1919 mill worker strikes in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Cenovia Santos and her husband moved to Texas from Coahuila, Mexico, in 1917, two of the thousands who fled the violence of the Mexican Revolution, but they remained in contact with their extended family south of the border. Phillip Bouchard’s youngest siblings spent several years in Waterville, Maine, orphanages during the Great Depression after their mother died, although their father was still alive.

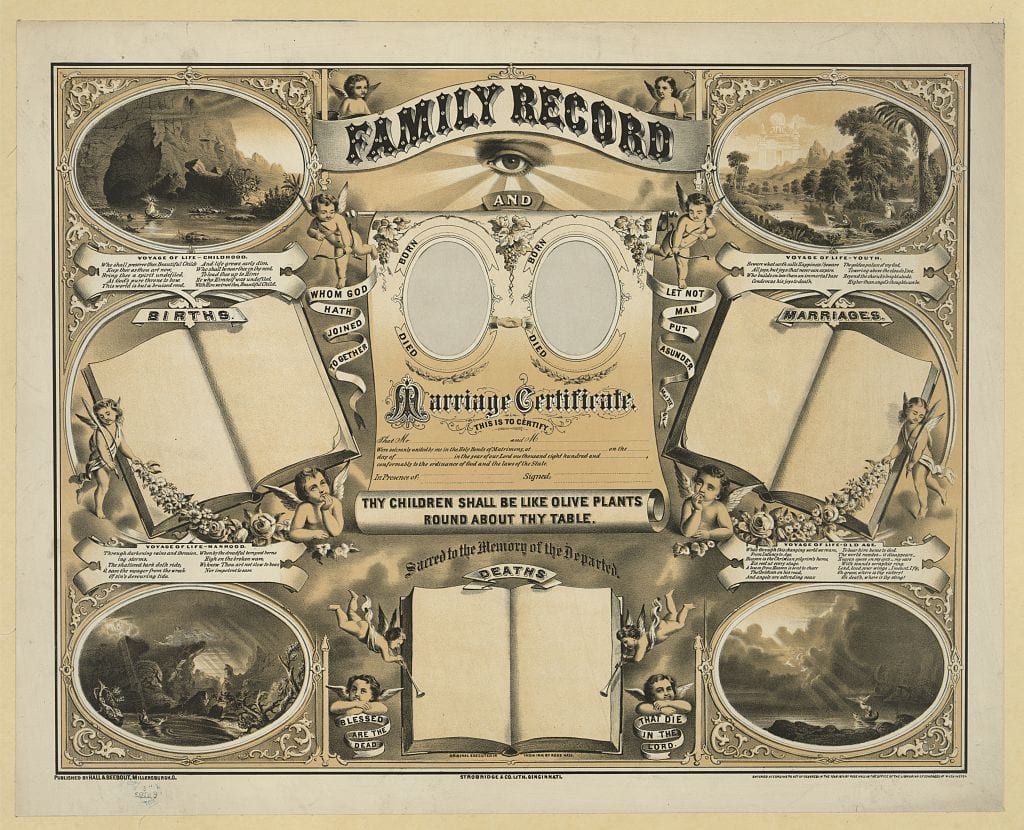

Using vital records, censuses, newspapers, and other documents, Mary Ann Mahony’s students fill in their family trees. Strobridge & Co. Lith./Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

These are just a few of the stories that have emerged from student research in my family history courses, most of which I have taught as sections of an undergraduate history methods class. Every semester, my department offers two or three sections of this 15-student research-and-writing-intensive course, each on a different topic or theme. Since it is a required course, sections reflect the broad cross section of our majors, who in turn represent Connecticut’s increasingly diverse population. At least half of our majors are first-generation college students, with diverse backgrounds including African American, Western and Eastern European, Canadian, Caribbean and Latin American, and South Asian ancestry. The methods course requires students to spend half of the semester learning about primary and secondary sources, locating scholarly articles in databases such as JSTOR, and reading examples of monographs and scholarly articles. Then they spend the second half of the semester researching, drafting, and revising a thesis-driven research paper based on primary sources.

In my section, students write papers that place their own family’s history in a broader historical and historiographical context. Using basic genealogical methods, they begin to build a family tree. They interview family elders. They learn to identify their female ancestors by their birth names. They move beyond a simple “who begat whom” framing to contextualize their ancestors’ experiences. They add their ancestors’ siblings and parents to their trees, learn about those extended families, and think about their ancestors in various life phases. They search for primary sources to document their ancestors’ lives and expand their trees. As they do so, they frequently move well beyond what their elders know.

The results have been extraordinary. Students are enthusiastic about their research assignment, engage in animated class discussions with peers, talk about their projects with their extended families, bring this experience into other classes, and write wonderful papers. In the process, they acquire essential elements of a history education, including the abilities to assess contradictory evidence, recognize change over time, and identify how their families’ experiences reflect the historical events and trends that they have read about for years.

Students move beyond a simple “who begat whom” framing to contextualize their ancestors’ experiences.

Over the course of the semester, students use many of the standard documents of genealogical research. They use birth, baptism, marriage, and death records; obituaries; census records; slave schedules; immigrant ship passenger lists; naturalization petitions; and newspaper articles, among others. In class, we discuss how to find these various document types and how to read them, so all students encounter examples of each type at some point during the semester.

Some students find evidence of family instability, including divorce, separation, children born outside marriage, and family violence. (Since the class does not include DNA testing, biological relationships are not tested or questioned.) These discoveries can cause embarrassment, consternation, and even shame, as students engage with their preconceptions about religious faith, premarital chastity, racial difference, ethnic culture, or a past in captivity. To help students process such information, early in the course I introduce documents about my family. At least two of my great-grandmothers bore children outside of marriage, although one married the father of her children days before the second was born and the other went home to Canada, where she told her parents that her husband had died. A third great-grandmother gave birth in such difficult straits that she placed my infant grandmother in a basket and left her on the steps of a Boston physician’s home in May 1884. Her case was not singular: page 217 of the 1884 Boston birth registry reveals numerous such children, all of whom appear to have had European ancestry. These examples do not eradicate all sensitivity around family stability, but they allow us to discuss the issues, with support from their historiographic readings, in a way that doesn’t reinforce erroneous assumptions.

Using genealogy in the methods class has had other unexpected benefits. Although not initially a goal, students emerge from the class with a less abstract and more personal view of history. Family history research forces them to examine their assumptions about the past as well as their current political and ideological positions. Many begin the class with strong opinions about hot-button issues such as immigration, slavery and freedom, gender, morality, race, ethnicity, and religion. As we examine and discuss the documents that they find, students confront the inhumanities of the Slave Schedules of the 1850 and 1860 US Census and the slave registers of the former British colonies. They see examples of two-parent Black families emerging from bondage and learn that many Puerto Rican families are Afro-descended. Through the examples of French Canadian and Mexican families, they learn about the experience of having relatives on both sides of national borders and making frequent crossings. Descendents of European immigrants find relatives who arrived in the United States without visas, as links in a chain of people from the same village, who never learned English and never became American citizens despite living in the country for decades.

These encounters with the lived experiences of their or their classmates’ ancestors challenge their assumptions about the past and present. The resulting class discussions are when some of the most interesting student learning takes place. Students learn about the deep roots of French Canadian, African American, Mexican, and Puerto Rican families in North America. They learn that most of their families moved to Connecticut in search of better opportunities, whether from the South, Canada, Italy, Poland, Ireland, or, more recently, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Mexico, and Pakistan. They also learn that the rules governing immigration to the United States in the past were quite different—and, at least for Europeans, usually much more lenient—than those current immigrants face, despite political rhetoric to the contrary. They perceive that white families’ apparent stability can obscure the terrible cost that women and children paid for transgressions and gain new sympathy for multigenerational matrilineal families that appear to be more accepting of women and girls who give birth to children out of wedlock. And many learn about the roadblocks that non-English sources present in pursuing their research. In other words, by incorporating genealogy into my classes, students become more complex thinkers as their understanding of themselves and their families, of their peers, of history, and of current political debates grows.

Encounters with their ancestors challenge students’ assumptions about the past and present.

Every semester, one or two students prefer not to research their own families or cannot find documents on them. As an alternative, they may locate a volunteer whose family history they can research, or they can research their hometown or nation of origin. With these options, everyone can find enough to write a research paper, which I grade based not on the number of sources they can find but on the quality of the evidence that they bring to support their thesis.

For this course to proceed well, access to a comprehensive collection of documents is essential. Numerous free websites are available for genealogical research, including FamilySearch, 10 Million Names, and Enslaved.org. I prefer Ancestry.com because almost all students can find something there related to their family’s past. The institutional version of the Ancestry.com World Explorer with the Newspaper.com add-on, to which our university library subscribes through ProQuest, provides over 11,000 document collections from all over the world (although the vast majority are from the United States, Canada, and Western Europe). An individual or family paid subscription offers access to over 33,000 collections and allows the subscriber to build family trees on the website and take advantage of the hints that Ancestry’s nominative linkage data algorithms provide.

Since their research is based primarily on digital genealogical resources, we also explore contemporary debates related to that type of research. We examine the relationship between Ancestry’s collections and the genealogy marketplace, the company’s roots in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, national and international privacy laws, the impact of political violence on document collections, and the millions of documents that have not been indexed and thus cannot be searched. We now discuss issues around artificial intelligence, which Ancestry has begun to incorporate. We also raise issues related to digital research. We usually agree that research in both digitized and undigitized sources is important, but that the ability to access sources remotely is essential for history majors at a university with limited research collections who do not have money or time to travel for research, even within Connecticut.

By the end of the semester, students produce microhistories embedded in their or someone else’s family experiences. Few students discover great men and women in their family’s pasts, but they all discover that the experiences of their ancestors are intertwined with major historical trends. They also learn that “history from below” can teach us all an enormous amount about the past. And they realize that the past, and therefore the present, is more complicated than they imagined. Over the course of the semester, they become more critical thinkers and see themselves and history in new, more nuanced ways. They become historians.

Mary Ann Mahony is professor of history at Central Connecticut State University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.