Most Americans today do not think about cake when considering this year’s election. But perhaps we should. Had we been colonists in New England or denizens of the new republic, cake would likely have been on our minds and in our bodies during election season. At our present moment, when political tensions run high and many Americans wait eagerly for the arrival of November 9, one might wonder why it’s worth thinking about cake and politics.

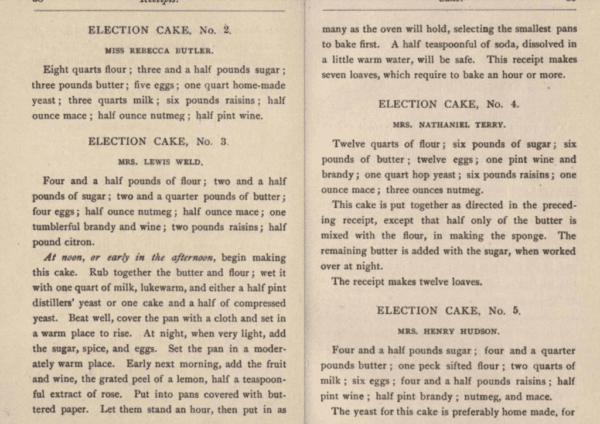

Hartford Election Cakes were popular in Connecticut well into the 19th century, as this cookbook published in 1896 suggests.

The history of election cake reveals an important American civic tradition that has been lost and largely forgotten. During the colonial era in New England, English immigrants and their descendants put naturally leavened, highly spiced fruit cakes at the center of political rituals. Known as “great cakes” in England, this dense, fragrant dessert took on different names and forms depending on the context in which it was baked and eaten in North America. When male colonists participated in militia training days (a requirement for all able-bodied men aged 16–60), women made “muster cakes” to feed the onslaught of hungry visitors who descended upon their villages. Military training days were festive, with people from surrounding areas coming not only to participate, but also to watch drills, socialize, play games, drink alcohol, and eat food like “muster cake.”[1]

OWL Bakery in Asheville, North Carolina, seeks to bring back the election cake tradition with its version of this historical treat. A portion of the proceeds from sales will be donated to the League of Women Voters. Credit: Susannah Gebhart

After the American Revolution, the cake became known as election cake. It was a special food reserved for a special occasion, when Americans treated Election Day as a revered holiday. Professional bakers and ordinary townswomen served the hearty cakes to the men who traveled to villages to vote, a process that usually took days because of the long distances required to reach polling places in rural America. In this era, when voting was a privilege granted to only the few—elite, property-owning white men—preparing, sharing, and consuming election cake was an informal way for some nonvoting American women to participate in the revelry surrounding election season. Unable to cast their own votes, they nevertheless contributed to the civic culture of celebrating the young republic through food.[2]

The first published recipe for election cake is credited to a white woman named Amelia Simmons who wrote American Cookery in 1796. This cookbook commemorated the new nation by highlighting its unique ingredients and dishes. Election cake (one of a few recipes with patriotic names, like “Independence Cake” and “Federal Pan Cake”) was massive in size and highly enriched. Simmons’ recipe called for 30 quarts of flour, 10 pounds of butter, 14 pounds of sugar, 12 pounds of raisins, a dozen eggs, and copious amounts of wine, brandy, spices, and fruit. Clearly, this cake was meant for a crowd—those who milled about polling places casting or counting votes, those who stayed overnight at boarding houses in villages far from home, or those who celebrated Election Day at fashionable, high-society balls.

Dr. Surdam’s students at Mars Hill University sample election cake, consider its history, and offer their own opinions about present-day voting culture and traditions.

White women of relative privilege would have been those most likely to buy and read Simmons’ book and others like it throughout the 19th century. But it is safe to assume that, at least in some places, enslaved women or indentured servants would have performed some of the labor required for preparing such a time-consuming cake.[3] The historical record leaves few traces of these women’s identities, but when they baked these special cakes, they too informed the civic traditions surrounding Election Day, an irony considering how distanced they were from formal political channels.

Election cake largely vanished from political traditions by the early 20th century. When recipes for it appeared in cookbooks of that era, they reflected new ingredients and altered techniques. The reasons for this are many. Baking methods changed. Flavor preferences expanded. New immigrants brought with them new food traditions. And, perhaps most obvious to those of us living today, Americans’ attitudes surrounding the electoral process have deteriorated, even though the right to vote has expanded to include more Americans—through long, violent, and ongoing battles. Citizens of this country no longer celebrate democracy through the act of preparing, baking, and sharing communal cake. It’s time for we citizens of the nation to take our voting rights seriously again. Those of us who can vote, must vote, and those of us who like to bake should consider making a cake to celebrate!

Notes

[1] David Freeman Hawke, Everyday Life in Early America (New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1988), 135–36.

[2] Nancy Siegel, “Cooking Up American Politics,” Gastronomica 8, no. 3 (2008): 53–61.

[3] Marylynn Salmon, “The Limits of Independence, 1760–1800,” in No Small Courage: A History of Women in the United States, ed. Nancy F. Cott (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 127.Image: Surdam.jpeg

The AHA Tries Election Cake! by Amanda Moniz

Dedicated historians that we are, we at the American Historical Association decided to sample an election cake as part of the #MakeAmericaCakeAgain campaign. I volunteered to make the cake using the OWL Bakery’s recipe and decided to use this project as an opportunity to explore the history of voting with my kindergarten-age daughter.

After making a few changes to the recipe, my daughter and I prepared the dough and left it to proof (rise). While the dough proofed, we took a family outing to the National Park Service’s National Colonial Farm at Piscataway Park in Accokeek, Maryland. The tobacco farm depicts the lives of a middling white family, the Boltons, in 1770. As we had mixed ingredients at home, I had talked with my daughter about the history of baking and the history of voting. The farm buildings and the very fine interpreters added to our exploration of both topics.

Poking around the buildings, we paid special attention to the kitchen. The dark space and the hearth were, of course, very different from our kitchen. Most notably, we learned that the family owned one slave, a woman named Kate, and that she had slept on a platform in the kitchen. Showing my daughter Kate’s sleeping space offered, I thought, a more effective way to convey the cruelty of slavery to a young child than my words could.

We talked with the interpreter playing Mr. Bolton about the family’s livelihood and about politics. He explained that he owned his land and therefore he had the vote. But he also explained that his crop hadn’t been good that year, which led to a more general discussion of the economy. We heard that because tobacco depletes soil so rapidly, rich landowners were buying up more land in the area. As a result, fewer men were becoming landowners and, in turn, the franchise was becoming more restricted.

Back at home, we baked the cake and, once it cooled, glazed it. Finally, time to taste! The aroma evoked bread, but the texture was cakey, which was what I expected, and the spicing was terrific. It was less sweet, though, than I thought it would be, even with the glaze. To my taste, it would go well with a morning cup of coffee.

So what about the history lesson? I asked my daughter what she thought people should know about the history of voting around the time of the American Revolution and about the cake. Her answers: You could only vote if you owned property. And definitely glaze the cake.

[See image gallery at blog.historians.org]

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Maia Surdham, PhD, is a co-owner of OWL Bakery in Asheville, North Carolina, and part-time professor at Mars Hill University. She has studied and written about migrant farm labor in the Midwest, and now explores culinary history, oral history, and Appalachian foodways. To learn more about OWL Bakery’s election cake fundraiser, or to bake a cake of your own, visit the website for details.

Amanda Moniz is program coordinator at the AHA and associate director of the National History Center.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.