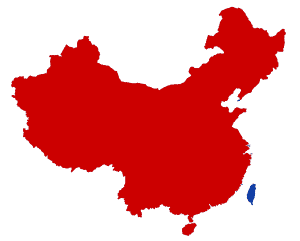

The Sydney Morning Herald and Vox.com agree that the recent dispute between Beijing and Taipei over a deportation decision by Kenya is nothing short of “bizarre.” Though the decision to deport Taiwanese nationals to China might seem strange on the surface, it in fact is deeply rooted in history.

This “bizarre diplomatic row” occurred after two separate deportation incidents involving China and Taiwan. The more recent began in Kenya, where officials acquitted Taiwanese citizens charged with tricking unwitting Chinese nationals out of their life savings over the telephone. Later, the Taiwan foreign ministry accused Kenya of submitting to pressure from Beijing and sending the alleged fraudsters to mainland China. An earlier case happened in Malaysia, where individuals accused of similar crimes were deported to Taiwan. In both cases, the host states accused Taiwanese migrants of a crime involving victims from mainland China, and both Taipei and Beijing demanded that the accused be deported to their own jurisdiction. While Taipei claimed the right to govern its own citizens, Beijing claimed both the right to govern all Chinese abroad, including travelers holding passports from the Republic of China on Taiwan, as well as the responsibility to seek justice for the fraud victims.

In short order, it becomes clear that where Malaysia or Kenya choose to deport alleged Taiwanese fraudsters holds significance for the status of Taiwan, the cross-strait dispute over sovereignty, and the recognition of Beijing over Taipei. Making the choice of destination for the deportees is an act of migration diplomacy: the use of migration policy to achieve foreign policy goals.

This state of affairs is not actually all that unusual for China-Taiwan affairs since the 1949 victory of the Chinese communists that forced the Republic of China to move to Taiwan. During the 1950s and 1960s, every time a foreign government chose who—the Republic of China on Taiwan or the People’s Republic of China on the mainland—could speak on behalf of Chinese nationals abroad, it was enacting a political maneuver in the tense Cold War atmosphere. Countries like the United States made their allegiances clear by emphatically trying to deport Chinese lawbreakers to Taiwan—even, at times, when the individuals involved had never been to the island before. Lack of diplomatic relations with the mainland complicated efforts to send Chinese migrants to their true homes. Moreover, sending deportees to Taiwan, also known in Cold War terms as “Free China,” affirmed its right as an American ally to claim sovereignty over migrants abroad.

That both Taipei and Beijing would claim the right to receive and prosecute accused criminals is also not without precedent. In 1956, in the context of the Sino-American Ambassadorial Talks in Geneva, the United States sought any kind of leverage available to secure the release and deportation of Americans imprisoned in China. In one exercise, representatives of the International Red Cross toured American prisons to question ethnic Chinese inmates about their desire to be released and deported. At Taipei’s insistence, prisoners were given the option of deportation to Taiwan as well as the mainland. Accepting even convicted murders and drug dealers attained symbolic importance as affirmation of the Republic of China’s sovereignty.

The present diplomatic debate over the deportation of Taiwanese citizens to mainland China demonstrates the power of migration diplomacy. Kenya uses the deportations to reaffirm sole recognition of Beijing and earn Chinese cooperation. In addition, China’s demands to accept the alleged fraudsters and prosecute them under its own legal system signals a clear challenge to the leadership of Taiwan’s new president, Tsai Ing-wen, and presents a warning against separatist tendencies from Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party. Finally, Taipei’s protest against the “extralegal abduction” of its citizens allows Taiwan to assert itself as a sovereign state in an international system that largely does not recognize it as such. The deportation of a couple dozen accused criminals thus has significant implications for the foreign policy priorities of all the governments involved.

Migration diplomacy has always had an important role to play in cross-strait relations, but it is not limited to that narrow context. Disputes over migrants, dissidents, deportations, refugees, and student exchanges often become opportunities for governments to signal larger foreign policy priorities, to make statements about their values on the world stage, and to control transnational movements that present challenges to their national policies and identities. This is true of the larger history of US-China-Taiwan relations in the 20th century, and of the recent European response to Syrian refugees, labor migration disputes in the Middle East, American responses to the sudden surge in the numbers of migrant children, and countless other situations. Controlling borders and protecting citizens are inherently international acts, so their breakdown into diplomatic rows is anything but bizarre.

Established by the AHA in 2002, the National History Center brings historians into conversations with policymakers and other leaders to stress the importance of historical perspectives in public decision-making. Today’s author, , recently presented in the NHC’s Washington History Seminar program on “The Diplomacy of Migration: Transnational Lives and the Making of US-Chinese Relations in the Cold War.” For a video recording of her talk, please visit: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5P2K2Pxe4zo

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Meredith Oyen is an assistant professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. She received her doctorate in history at Georgetown University. Oyen specializes in the history of US foreign relations, Sino-American Relations, and Asian immigration. Her first book is The Diplomacy of Migration: Transnational Lives and the Making of US-Chinese Relations in the Cold War (Cornell, 2015).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.