Living next to a World War I memorial arch, David Trowbridge, associate professor of history and the director of African and African American Studies at Marshall University, witnesses a daily performance, multiple times a day. People stop at the memorial, look around for a few minutes “truly curious,” and then leave. Without much information on the arch apart from a reference to the Great War and the names of some soldiers, the visitors leave without discovering the history behind the arch. With Clio, a website and mobile app that uses GPS technology to deliver historical information about nearby sites to users, Trowbridge, however, hopes to catch people at their “moment of curiosity” about a particular historical monument or marker. With Clio’s help, visitors to the World War I memorial, for example, can uncover troves of information about the arch and its history. The app, as Trowbridge describes it, gives historians the power to engage with people when they are most interested.

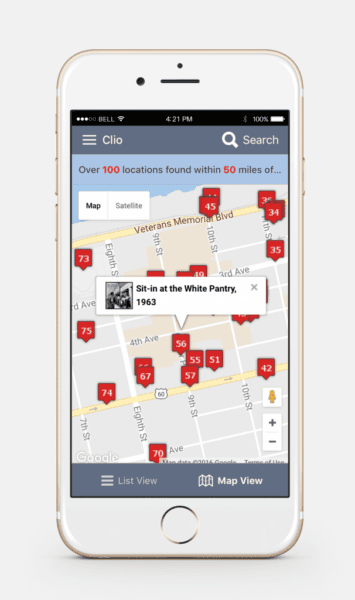

Clio helps users find and learn about important historical historical landmarks, monuments, and museums geographically near to them. David Trowbridge

Designed to serve as a guide to the public to the “thousands of historical and cultural sites throughout the United States,” Clio currently boasts nearly 30,000 historical entries in its database. Using Clio, history enthusiasts can embark on suggested walking or driving tours or create their own itineraries. Each entry in Clio includes a short summary about nearby historical sites, monuments, or museums, as well as links to relevant scholarly works and primary sources.

AHA Today first spoke to Trowbridge about Clio in May 2016, when he received a Whiting Public Engagement Fellowship to support work on the project. Since then, the project has grown, both in terms of its technical capacities and the number of entries on the website and app. Some of the funds from the $10,000 Whiting fellowship, says Trowbridge, went toward developing capacity for walking tours as well as integrating Clio with Google Street View, which allows people to place pins on locations of historical markers or monuments. The mobile app also introduced a “Discovery” mode, which identifies the seven closest historical sites to users on a map and updates while they walk or drive.

The Whiting Fellowship also gave Trowbridge time to improve educational and instructor resources. “Clio in the Classroom” allows instructors to work with students to create entries for the project. Students going through the process of creating entries for Clio develop numerous skills, including how to research, organize information, and communicate it to the public, says Trowbridge. Instructors can now create special accounts that let them “track and provide feedback for each of their student’s entries from the first draft to the student’s final submission,” says Trowbridge. A new “Citation Helper” helps students correctly cite sources, and a peer review function lets students provide feedback to their peers before submitting entries to their professors. Trowbridge hopes that these features will allow instructors to devote their time and energy to providing “substantive feedback” to students’ entries. He notes that each entry, when it comes to him for approval, includes the name of the student author and the instructor, making both accountable and reassuring him that the entries are rigorous.

The Whiting Fellowship further facilitated the creation of new features for instructors, such as the capacity to create interactive walking tours and heritage trails. Jennifer Barker-Devine, an associate professor of history at Illinois College, used Clio with her first-year class, asking students to create entries for their local area and give presentations to community organizations. In a survey taken after the class, most students reported that they planned to use Clio in their personal lives. (Barker-Devine wrote about using Clio on her blog.)

Now, Marshall University has a new NEH grant to support Clio. According to Trowbridge, the university plans to use the grant to work with historians in West Virginia to “create walking tours and heritage trails that connect residents and visitors” to the state’s history. The grant will provide stipends for scholars and paid internships for students over the next few years. Trowbridge emphasizes that anyone can incorporate Clio into their grant applications, or as a solution to the question of how to better reach the public. “If my work supports the work of my colleagues in that way,” he says, “I can’t tell you how happy I’d be.”

As far as Clio’s future, Trowbridge says that he is currently working on building capacity for audio tours. He hopes that people will eventually be able to leave their phones in their pockets as much as possible. He also wants to increase the number of users who click on books and articles through Clio. “There is a strong connection between our sense of place and our sense of the past,” Trowbridge tells AHA Today, “and I want to offer a platform that reaches people at those moments of curiosity and encourages them to explore further.”

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.