One of the most widely shared images from the August 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, was the statue of Robert E. Lee, with a church steeple in the background. Just to the left of the statue though, standing in stark contrast to the black shields of the North Carolina racists at the front of the picture, is a man holding two items—a confederate battle flag and a white shield emblazoned with a red cross. The sight of the shield conjures the Knights Templar and the so-called “Crusades,” an allusion confirmed by the words flanking the cross, “Deus Vult.” The phrase, Latin for “God wills it,” was supposedly shouted by the crowd at Clermont in 1095 CE, then on the battlefield as that army of Christians marched toward the conquest of Jerusalem in 1099.

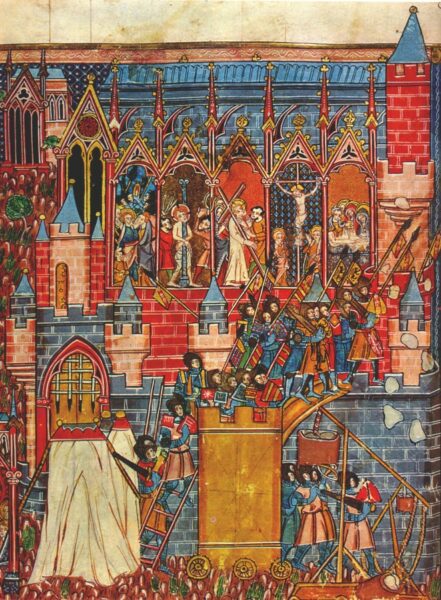

White supremacists have linked the memory of the medieval Crusades, including the 1099 Siege of Jerusalem, with that of the American Civil War. Ökumenisches Heiligenlexikon via Wikimedia Commons

This pairing of images from historical moments separated by a sea, an ocean, and more than 750 years was striking both for their juxtaposition as well as for how natural a fit they seemed together for the white supremacists themselves. Something connected for them the memory of the Crusades and American Civil War, a nexus forged at the feet of an early 20th-century statue—a double nostalgia, commemorating in 2017 a 1924 commemoration of events of the 1860s (a period that was itself, as several authors have discussed, nostalgic for an imagined medieval past). But there’s much more to say about the parallel processes by which these two wars have been commemorated and why they both find such purchase on both sides of the Atlantic among white supremacists. This was the impetus for the panel I organized for the upcoming 2019 AHA annual meeting in Chicago—jointly presented with the MLA annual convention—bringing together historians and literature scholars, medievalists and Americanists, and entitled “Nostalgia and Narrative after Charlottesville: Comparing Myths of Origins in the Middle Ages and the American Civil War.”

The issues to be unpacked here are manifold. Focusing on my own particular area of expertise, we must first acknowledge that the contemporary white supremacist fascination with the European Middle Ages did not by any means begin with the events of Charlottesville. It was, however, brought to wider attention by Sierra Lomuto, who wrote a prescient piece not long after the November 2016 election reminding medievalists to consider the ethics of studying the Middle Ages in an era of resurgent white nationalism. Her prophecy was rendered visible with the events of Charlottesville. After that event, the Medieval Academy of America and affiliated societies strongly condemned the appropriation of medieval symbols to support hate; individuals wrote trenchant pieces, sometimes for popular periodicals; I myself organized a symposium bringing together scholars and journalists to better understand nostalgia, specifically for the Crusades; and other scholars talked with journalists about the phenomenon.

Over the last year or so, issues of popular appropriation and academic historiography have continued to receive attention at professional conferences such as the annual medievalist gatherings at Kalamazoo, Leeds, and the Medieval Academy, as well as more subject-specific meetings such as the recent one focused on the legacy of Belle da Costa Greene and her meaning to medieval studies at St. Louis University or my upcoming conference on comparative nostalgia around the Crusades and American Civil War.

By recounting all this movement within medieval studies against white supremacy, I don’t mean to suggest that all is proceeding smoothly, that there’s nothing left to be done. Far from it. Colleagues face harassment, conference organizers struggle with the new reality of the field, and we as scholars need to understand and confront the structures and practices that can drive away colleagues from traditionally underrepresented backgrounds.

But the willingness of historians (along with scholars from other disciplines) to have these conversations, to attempt to throw the light of truth on these issues, in venues as diverse as the AHA annual meeting and the Washington Post, for instance, seems to me encouraging. Ours is not the only panel on this topic at the AHA 2019 annual meeting in Chicago. Another session on decolonizing medieval scholarship and still another on strategies for teaching a diverse, global Middle Ages to undergraduates seem particularly exciting.

Also encouraging is the new energy directed to talking with people outside our narrow research specializations. Again, our session at the AHA 2019 annual meeting brings together scholars working in different disciplines, in varying types of academic positions, at different types of institutions, from different regions of the country, who research different continents and time periods. This was, in part, made possible by the willingness of the AHA and MLA to collaborate, to offer registrants to either conference admission to both, to think about the different conversations that happen in different spaces, and open up opportunities to have those conversations. But it was also made possible by generous colleagues, scholars who are willing to explore a topic with one another, to be intellectually vulnerable, and to really think through a problem with people who approach it in different ways. And finally, these sessions were made possible by a shared commitment to do more public-facing work.

There may well be cause for alarm about the future of history at US colleges and universities but that concern might be overblown. Historians, studying every period and place, from antiquity through the Middle Ages and into modernity, are not just having the same conversation over and over but are actually doing something, moving the conversation forward, and demonstrating that history has a vital role to play in contemporary society.

Matthew Gabriele is a professor of medieval studies and chair of the Department of Religion & Culture at Virginia Tech. He is a contributor at Forbes.com and tweets at @prof_gabriele. Gabriele thanks Dr. Sierra Lomuto for reading and commenting on a draft of this piece.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.