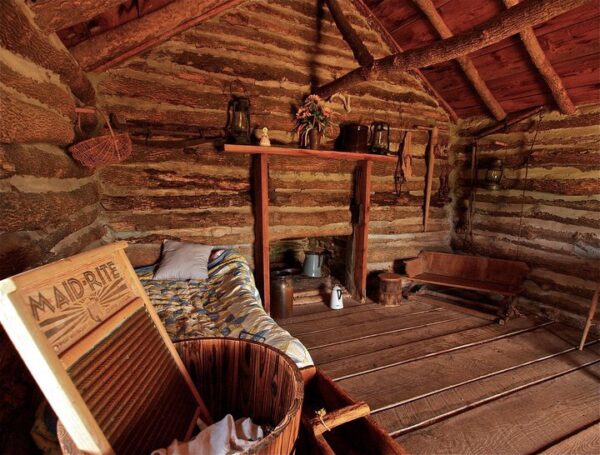

When I began my directorship of the Little House on the Prairie Museum south of Independence, Kansas, the promise and challenges the museum faced swirled in my mind. For any small historic house museum, problems tend to outweigh the possibilities. Founded in 1977, the Little House on the Prairie Museum preserves the Kansas homesite where Charles Ingalls and his family lived from 1869–71. The museum features a replica of the one-room cabin the family lived in while in Kansas along with a 19th-century one-room schoolhouse and post office moved to the site to ensure their preservation. At times I found myself thinking morning, noon, and night about fundraising, budgets, site repairs, increasing visitation, pushing back against the false images perpetuated by the wildly popular television show, and making the site historically meaningful. With a full-time staff of one (myself) and two part-time employees, I had more tasks than time.

A replica cabin at the Little House on the Prairie Museum commemorates the Kansas home of the Ingalls family from 1869–71. Photo courtesy of author

As a practitioner of first-person living history interpretation I worked diligently to ensure that visitors experienced aspects of pioneer life that children’s author Laura Ingalls Wilder chronicled in her now famous books. I added to her writings other aspects of daily pioneer life—soap making, laundry, open hearth and pit cooking, gardening, sewing, and quilting—after hours of meticulous research. My living history volunteers were not only outfitted properly, they were also well versed in the history of the time period, the region, and the Ingalls family. When I left my position in July 2015 to pursue my doctoral studies I felt that I had done all I could to create meaningful interpretive experiences for our visitors. After attending this year’s AHA annual meeting in Denver and listening to Ivan Gaskell (Bard Graduate Coll.), Tiya Miles (Univ. of Michigan), and Laurel Thatcher Ulrich (Harvard Univ.) discuss teaching strategies utilizing historic house museums I realize now that I did not achieve my goal of meaningful artifact interpretation despite my best efforts. The varied experiences of Gaskell, Miles, and Ulrich provide historians and living history interpreters with creative strategies to connect visitors to tangible aspects of the past. As a museum professional, I wish I would have been privy to their expertise and experiences when I began my tenure as director.

Ivan Gaskell, for example, used a 34-star flag at the General Artemis Ward home in Shrewsburg, Massachusetts, to create a window into the lives of soldiers, both Union and Confederate. Tiya Miles assessed the Chief Vann House, perched atop Diamond Hill in Georgia, and its role in cross-cultural relations between Cherokee, African American, and white communities to highlight the limited range of historic house interpretation that impacts their potential to speak to diverse audiences. A simple dinner bell used by Brigham Young to call his wives and children to dinner provided Laurel Thatcher Ulrich with a tangible link to daily life for the women in the Lion and Beehive Houses in Salt Lake City. These three scholars all used a physical aspect of the past, located on the grounds of a historic house museum, to reinterpret the past and to situate the homes within a wider scope of American history.

A Little House on the Prairie Museum exhibit features an example of a trunk carried by pioneers when they travelled. Photo courtesy of author

Speaking on the panel, Gaskell outlined the importance of historic house museums as “overlooked repositories of unwritten history.” As I sat listening, my mind reviewed my own interpretation efforts at Little House. Did I embrace our site in this manner? Miles, for example, discussed the marginalization of slavery in the interpretive efforts at Vann House. “Tourism, the main goal that led to the home’s preservation, reinforced whiteness in the historical narrative,” she said. Immediately I wondered if I had done enough to frame the Ingalls home as a contested, shared space that was primarily Osage in nature. When Ulrich described historic house museums as places where “stories are hidden in plain sight,” I thought about the missed interpretive opportunities at Little House that I did not see and walked by every day. Perhaps I was afraid to shatter the hopes of the overjoyed Laura fans that visited our museum expecting meticulous recreations from her book and the television show. For me portraying the history of 19th-century pioneer families, like the Ingalls, demanded that I integrate her experiences (as chronicled in her book) while steadfastly denying the television interpretation of her life and times.

Michelle Martin portrays Caroline Ingalls and demonstrates how water was carried from the creek to cabin before Charles dug a well for his family. Photo courtesy of author

Today, more than ever, historic house museums and their staff are challenged by a public that wishes to be entertained and informed. In retrospect, I should have focused more interpretive efforts on Charles Ingalls’s hand-dug well that provided his family with water. How did something as simple as a well change his wife Caroline’s daily life? Instead of recounting the harrowing tale of digging the well, preserved in Laura’s work, how that well freed up valuable time for Caroline to sew, cook, tend to her children, or perhaps even have a few moments of respite could have done a great deal to educate our visitors about the importance of natural resources and labor-saving devices to a pioneer family. By locating the well close to the family cabin, Charles also eliminated a perceived security threat to his family as they no longer traveled to the creek where the local Osage populace also obtained water. However, a potential point of cultural interchange and understanding that could have developed between his family and the Osage on the banks of the creek was also stifled.

Only while listening to Gaskell, Miles, and Ulrich did I come to understand how one single artifact or locale could provide multiple contexts for interpretation. For them, historic house museums, and the artifacts they contain, are tangible tools to share complex, sometimes difficult, historical narratives with the public in a nonthreatening way that educates, entertains, and hopefully inspires visitors to look beyond the façade and to see that history is in everything.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Michelle M. Martin is a second-year doctoral student at the University of New Mexico. Her research interests focus on the intersection of gender, race, and ethnicity in the Indian Territory (Oklahoma) from 1850–1900. Martin is also an accomplished living history interpreter who portrays 19th-century American women in the West.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.