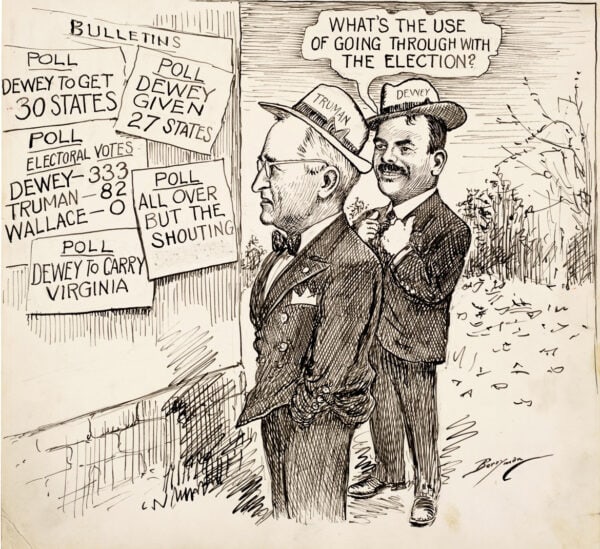

Clifford K. Berryman, “What’s the Use of Going Through with the Election?” (October 19, 1948)/US Senate Collection/Center for Legislative Archives

It’s mid-November 2016. The context: the election of Republican Donald Trump, who will take office in 60 days. Subcontext 1: bias crimes, harassment, and intimidation of minority groups and immigrants, reported anecdotally and to police and legal groups. Subcontext 2: demonstrations against the incoming administration in cities around the country, with chants including “Not my president!” and “No hate, no fear! Immigrants are welcome here!” Subcontext 3: the appointment of two senior administrators who stand to the right of many Americans, even Republican Party leaders. One, Stephen Bannon, was chief executive of the site Breitbart News, which under his watch published incendiary white nationalist, misogynist, and anti-Semitic stories. Subcontext 4a: social media, where Trump supporters tweet “Dear Liberals,” along with told-you-so, aggressive, too often derogatory comments about minority groups, students, and women. Subcontext 4b: social media, where liberals, leftists, and Democratic Party supporters parse white women’s lack of enthusiasm for Hillary Clinton, despite evidence that the president-elect has repeatedly sexually harassed and assaulted women. Another left critique focused on Clinton’s supposedly limited appeal to the white working class. Subcontext 4c: social media, where people of color, immigrants, and LGBTQ people post reports of harassment and assault, express fear, and “welcome” white allies to their world. Subcontext 5, which runs most deeply and which you might judge most important: the eight-year campaign to undermine the country’s first African American president, fueled by the current president-elect, who only disavowed his years of lies about the president’s birthplace and religion in September, months after his nomination.

There is more context, there are more local stories in addition to this big picture, there is the historic movement called Black Lives Matter, which I hope has not been ignored in your textbooks. But these pieces of context are factual, and whether you’re working on a project for a high school history class or researching a dissertation, you can begin here. We’re historians; facts matter.

What I can tell you in addition is that late 2016 is a difficult time to be a historian. For the past year, Americans have looked to us for answers, for explanations, for reassurance, for precedents, for predictions. A few months ago, a number of historians formed a group called Historians against Trump, and some recorded a series of videos called Historians on Trump. Have at these as primary sources, if they can be found. The most pressing question coming from the public and the media was always whether Trump represented a recapitulation of fascism. Or Nazism. His comments on undocumented immigrants when he announced his campaign in 2015 included a reference to them as rapists, his promises to deport them upon taking office drew him attention during the Republican debates, and he reiterated this promise on 60 Minutes shortly after his election. Reasonable people were reminded of anti-Semitic scapegoating and railroad cars that took deported Jews to death camps.

I hope that analog now sounds extreme, but the rise of Nazism was invoked everywhere; you’ve probably found plenty of examples already. Maybe you interpret the rise of the Third Reich differently than we do today, but it wasn’t uncommon for today’s Americans to hear, ominously, that Hitler was “democratically elected” in 1933. (He received less than 44 percent of the popular vote.)

There are problems with this parallel, most significantly the fact that it transfers a leader and an event from a bygone context to the present. Although it’s possible that no historical epoch has been studied more extensively, allusions to fascism and Nazism seemed to become attenuated as the campaign went on. The desire to take “lessons from history” was strong inside and outside the discipline, and historians fought to clarify what was at stake. Yet it became clear that our methods, including deep skepticism about drawing such lessons from the past, didn’t speak to the questions the media often posed.

For the past year, Americans have looked to historians for answers, for explanations, for reassurance, for precedents, for predictions. It is clear that our methods, including skepticism about drawing lessons from the past, didn’t speak to the questions often posed.

There were parallels to fascism during this election, but they were never singular, never tidy. Moreover, there were other intriguing analogs. As many Americanists pointed out, champions of Populism during the late 19th century spoke on behalf of farmers who were squeezed by the vise of corporations, postbellum deflation, and unfavorable monetary policy, some of them harnessing anger at the Republican Party for policies that supposedly benefited African Americans at white men’s expense. But that parallel to Trump was uncomfortable too, perhaps because historiography on Populism remains contentious and diverse (as it should be). The rancid racism of “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman didn’t square with other Populists’ expansively democratic ambitions. It may be that Trump’s election has ultimately done away with this ambivalence and that you look on complex interpretations as signs of decadence.

If you dig a bit deeper, you’ll see we also talked about Fillmore, Pierce, and Buchanan: weak chief executives whose election emblematized the context for extremist, pro-slavery pieces of legislation, the war for Kansas, and the Dred Scott decision. Not letting liberal FDR off the hook, we talked about Japanese American internment (Executive Order 9066). We talked about Nixon, about the southern strategy, about “law and order,” a slogan born of disgust at protests, in 1968 and 2016 alike. We talked about Reagan’s betrayal of the Democrats who voted for him through union busting. We also talked about the Clinton administration’s neoliberal policies as laying the groundwork for the disaster of 2008 and the class discontent of 2016.

So much for presidents. And perhaps for precedents.

What you might not realize about the context of 2016 is that for several (or many) years historians and other humanists have been battling to justify our existence. State budget cuts to public higher education, especially to non-flagship colleges and universities, have attenuated programs deemed frivolous because they don’t prepare students for specific careers. This argument has been convincing to many students and their parents, who must reckon with soaring tuition and the possibility of years of student debt repayments during what still feels like a recession.

One notable aspect of the 2016 presidential campaign was Republican attacks on the so-called political correctness of the Democratic Party. You have probably already interpreted the extent to which identity politics and its flashpoints—gender-neutral public bathrooms, marriage equality, safe spaces, and trigger warnings—contributed to the Democrats’ defeat. (Certainly, we’ve been debating it for days, but you might not realize that some of these things were controversial among professors. Whatever you think now, in November 2016 there was hardly a consensus about these issues.)

I would call your attention to the invocation of history in the backlash after the election. Swastikas popped up in elementary schools and on churches, summoning a specific politics as well as a specific interpretation of history. Fliers posted in universities across the country demanded an end to anti-white propaganda in college. Calls to teach “white history” increased—or rather, were replayed, at higher volume, from the debates about the Confederate battle flag following the murder of several African American worshippers by a white supremacist in 2015.

It’s true, white history is a field that doesn’t exist among professionally trained historians, though we haven’t shied away from writing plenty of history with white people in it, nor do we hesitate, really, to speak of the history of whiteness—though, if you can find our syllabi, you’ll undoubtedly see that we don’t generally organize our courses around it. White history as imagined by racists who take a stand against what they see as political correctness has no legitimacy among us. I hope it has no legitimacy among you, either.

It’s impossible for history to disappear. People will always be curious about where they came from, what people in the past were like, their stories of triumph over difficulties, of rising to challenges from childhood to death. You know this, you enjoy wondering about these people, like us; you probably engage in parlor games with others like you about the three famous dead people you’d have dinner with.

As Walter Benjamin had it, history is written by the winners—to the victors, the spoils. Historians of November 2016 can’t be sure, ultimately, who you will judge were the winners from your own perspective; that depends on your own context and your own biases. I’d like to think you’re still avoiding objectivity as a platonic ideal for historians, that the insight that facts aren’t things simply waiting to be discovered still has life. I’d also like to think that you haven’t buried histories of the search for justice as irrelevant or, worse, quaint. If this sounds familiar, take a dip into our historiography—the American Historical Review and Perspectives on History make good starting points—and you’ll discover how we viewed the past: as complex, shifting, dynamic, and difficult to draw easy conclusions about. (Indeed, you may find our syntax stilted or unnecessarily complicated, but we often struggled to capture the past in words.) If these histories seem completely unfamiliar to you, even bizarre, try to project yourself into a world in which they once made sense. We call this empathy, and I hope it’s a skill you try to exercise and teach.

And know, too, that our histories weren’t displaced without a fight, if in fact they have been. Today’s historians as teachers, as writers, as researchers, and as citizens both built upon and overturned years of interpretations of nations, events, movements, commerce, and power. Our edifice is strong. Our will is stronger. See you in the future.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.