On April 15, 2019, the cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris caught fire and burned. Alongside people across the world, I watched in horror and disbelief as flames engulfed first the scaffolding erected to repair the cathedral’s spire, then the roof, and finally the spire itself. In shock, we were glued to our screens as smoke billowed from the middle of the building and the fire devoured the timbers beneath the lead roof. By 7:30 p.m. in France, the fire had compromised the central crossing tower. The majestic 19th-century spire collapsed and fell through the roof of the nave. By late evening, the “forest of Notre-Dame,” the oak timber lattice framework that held the roof aloft above the chevet, crossing, and nave, had almost entirely burned. The fire grew so hot (between 600 and 1,300 degrees Celsius) that it melted the lead roof and sent great plumes of eerie greenish smoke into the evening sky.

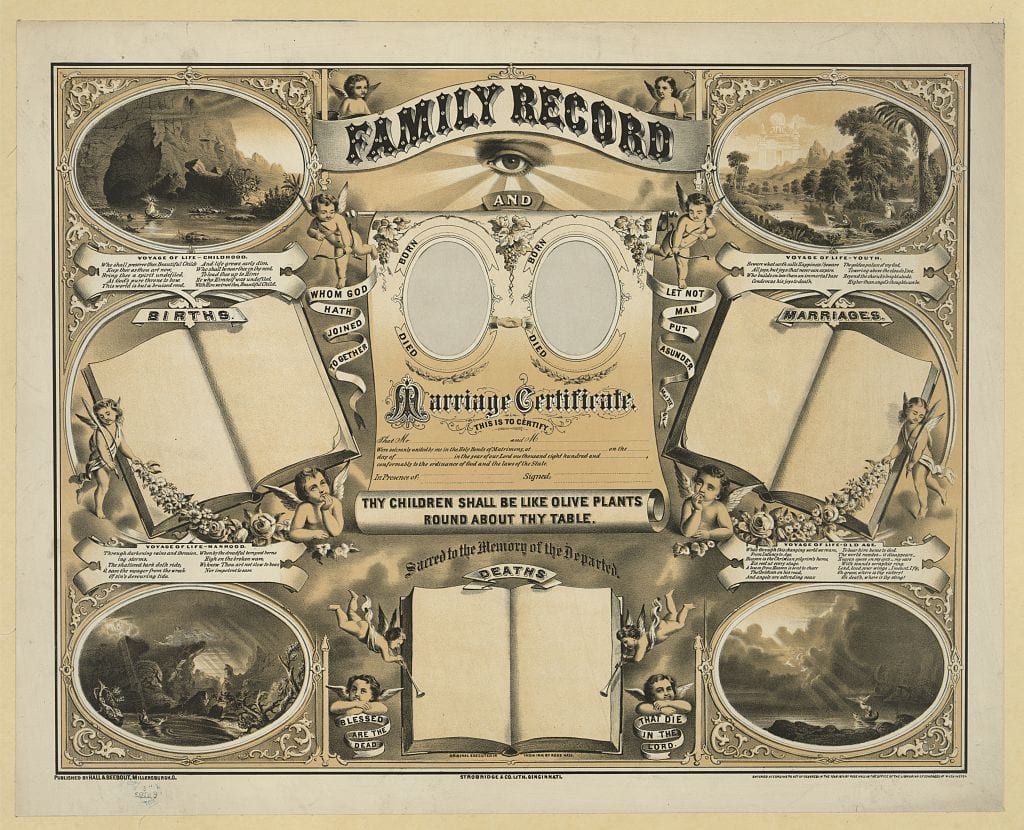

The scaffolding of Notre-Dame, photographed by the author on June 16, 2024, highlights the artisans working to rebuild the cathedral. Anne E. Lester

Rescue crews and firefighters worked tirelessly to save what they could and to put out the blaze. The chaplain of and a group of canons recovered the cathedral treasury’s most precious relics, including the Crown of Thorns and the chemise of Saint Louis, which were taken to the Louvre. At 11:30 p.m., President Emmanuel Macron addressed the public, vowing to rebuild within five years. By midmorning on April 16, the fire was out, and the work of resurrecting Notre-Dame began.

A historian of medieval religion and society and a specialist on medieval France, I found myself answering questions from the US media about what the cathedral meant in the past and in the present; speculating about what had been saved and what was lost; and reflecting on what the building meant for me, for “history,” and for the people of France.

In the process, two points emerged for me. First, while Notre-Dame has tremendous personal and religious meaning to Christian believers in France, it is also a symbol of national and international significance, and it remains one of the most visited pilgrimage and tourist sites in Europe. The loss of parts of Notre-Dame is culturally and historically jarring; it ruptures a deep continuity. This was palpable as we gathered around the globe in front of our televisions and live streams to gasp, cry, wonder, lament, and share the shock and loss.

Second, the loss was something more than a medieval edifice. As I emphasized at the time, we also lost the know-how of past artisans and laborers; now gone was the unwritten archive that held the knowledge of how to construct a monumental timber roof structure, vaulting, and columns. The efforts of nameless medieval workers are now effaced. Although the cathedral is being rebuilt, it will not and cannot be the same building. We do not have the same skills or resources. The medieval woodlands and great oak trees that supplied Notre-Dame’s “forest” roof framework are gone. Nor can we source the same stone from the same quarries or replicate the tools and techniques in the same manner. Our material world is different. Although parts of the building could be restored, the central crossing and much of the timber and stonework have had to be built anew.

Notre-Dame remains one of the most visited pilgrimage and tourist sites in Europe.

Rebuilding Notre-Dame has been a complex undertaking. The building we know now was constructed over an older Merovingian cathedral structure that had been somewhat enlarged during the ninth-century Carolingian period. The Gothic edifice was begun in 1163 and continued over the next 150 years. During that time, techniques shifted—as researchers have discovered—and new feats of engineering enlarged the windows and give the illusion of floating the stone roof above parishioners.

Notre-Dame continued to evolve. It was prey to the iconoclastic destruction of the French Wars of Religion and the Revolution, when the gallery of kings that ran along the facade was torn down and the statues decapitated (the heads, which had been buried nearby, were found in 1977 and are now on display in the Musée de Cluny) and the cathedral was briefly “converted” into the Temple of Reason. By 1804, however, it was the site where Napoleon crowned himself emperor, and within a year Pope Pius VIII recognized Notre-Dame as a minor basilica. Between 1844 and 1864, Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc and Jean-Baptiste Lassus restored its towers, buttresses, and roof, adding “medieval” flourishes including gargoyles and the iconic 19th-century spire. Paris’s cathedral is and always has been a living building, and therein lies some measure of consolation. The fire and subsequent rebuilding and restoration efforts will be part of its continued history.

Indeed, in the aftermath we have learned a tremendous amount due to incredible scholarly and state initiatives. In the days after the fire, leading researchers and politicians formed the Association of Scientists in the Service of the Restoration of Notre-Dame Paris to offer guidance to the rebuilding project. A second panel formed to coordinate and supervise the practical realities of rebuilding under the direction of Jean-Louis Georgelin, an army general who oversaw nearly 1,000 artisans around France. Initially, the association brought together over 175 researchers and scientists tasked with an expansive research agenda grounded in history, archaeology, geology, chemistry, and many other disciplines. In announcing their goal in rebuilding, the team cited French medievalist Jacques Le Goff, who stated that “to be reborn is not to return, it is to start again.”

The new research that has emerged is staggering, encompassing medieval cathedral construction, repair, building techniques, and more. Under the leadership of Maxime L’Héritier and Philippe Dillmann, nine working groups endeavored simultaneously to evaluate and understand the wood, stone and mortar, glass, metal, structure, decor, acoustics, digital data, and meanings of Notre-Dame as a heritage site.

Digital models helped scholars recognize the structure’s proportions, stresses, acoustics, and engineering. Others studied the surviving and charred roof timbers using chemical analysis, carbon-14 dating, and other techniques to examine the wood’s origins; understand how it was treated, cut, dressed, and assembled; and assess what could be gleaned about the climate during the medieval period when the trees were felled. The charred stones underwent similar analysis. Another team uncovered a series of iron pins used in the construction of the interior limestone walls, revolutionizing our understanding of how building forms transitioned from the late 12th century into the 13th, when Notre-Dame leapt into the Gothic style. Chemists, botanists, and environmental scientists analyzed the lead used in the medieval and 19th-century roof and stained glass. To evaluate the lead released by the roof as it burned, others monitored state-maintained beehives within a measured radius around Paris to determine lead levels in new honey. Another team built on an earlier sound map of Notre-Dame’s interior to reconstruct a space acoustically as close to the original as possible, in the process learning much from the cathedral’s original soundscape, where new musical forms and variations like the polyphonic motet were first composed in the mid-13th century.

The new research is staggering, encompassing medieval cathedral construction, repair, building techniques, and more.

A host of studies emerged about cultural heritage and monumentality, in turn advancing techniques of digital modeling and aspects of data science. Anthropologists, sociologists, and cultural theorists have analyzed reactions and responses to the fire and to ideas around rebuilding and cultural heritage more broadly. Several studies focus on materiality and sentimentality of building spaces. Analysis of the emoji used in social media posts in the five days after the fire showed that feelings of mourning and resolve briefly united people across the globe. The idea that space and materials endure through time suggests why it is that cultural heritage—spaces and sites that are deemed of specific significance—can hold a special status for communities locally and globally. And there is no doubt that in the decades to come, far more research will emerge from the ashes. As Maxime L’Héritier’s team put it, “Notre-Dame thrives on science, but science thrives on Notre-Dame.”

Finally, we have much to learn from those involved in the reconstruction itself. Researchers assessed how best to rebuild while using medieval techniques as a precedent. The contemporary experience of rebuilding—the use of massive cranes, layers of scaffolding, and “spiders” (cordistes), workers who “fly” or hang over the building site in harnesses—illuminates medieval construction techniques and what feats of engineering were possible in the cathedral’s initial construction. And while advertising was banned from the worksite, portraits of workers graced the scaffolding flanking the cathedral’s iconic flying buttresses. Although we know little about those who originally built the cathedral, having in public view the stories and labors of today’s workers shows what expertise and efforts lie behind the making of a monument.

Unfortunately, political pressures to meet Macron’s promise and complete the project in 2024 have limited the extent of research undertaken. For example, although archaeological work was conducted, much remains buried under the nave. One hopes that in time selected trenches can be opened for additional excavation. Certainly, a great boon of information and new techniques will continue to deepen our understanding of the medieval cathedral and its long afterlives. Meanwhile, ethical questions remain about how best to use public funds and private donations in cultural heritage projects like rebuilding Notre-Dame, and they deserve future scrutiny.

As I write this in October, the cathedral’s major structural elements have been repaired or rebuilt. Crews have removed much of the exterior scaffolding, the Grand Organ and the damaged stained glass windows have been repaired, and decorative iron work and railings have been restored or replaced. The timber framework of the nave roof and choir has been completed, the interior stonework refaced and repainted, and the rebuilt spire set in place, visible now from across the city as it once was. The lead roof is being reset as I write. Notre-Dame is scheduled to reopen to visitors on December 8, 2024, a feat that seems nothing short of miraculous.

Anne E. Lester is John W. Baldwin and Jenny Jochens Associate Professor of Medieval History at Johns Hopkins University. In 2024–25, she is a Visitor at the Institute for Advanced Study.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.