At last year’s annual meeting, in New York City, the poster session continued its impressive run as a highlight of the meeting. Ample audiences took advantage of the capacious and well-lighted venue to engage with the posters, sometimes by scanning them from a distance, at other times approaching the authors to view their work and discuss it. The scholars demonstrated knowledge of a remarkable range of topics addressed with an especially impressive methodological breadth and sophistication. Taking it all in was quite a task, but I found it more than worth the effort.

A scholarly poster is a condensed form of academic or pedagogical presentation that defines an issue and delivers a message in the space of a single canvas, often created on PowerPoint, of roughly 30 by 50 inches. The academic poster genre is traditionally important in the natural sciences, where concise statements of experimental issues lend themselves readily to the poster form. For history, such a presentation of complex materials presents

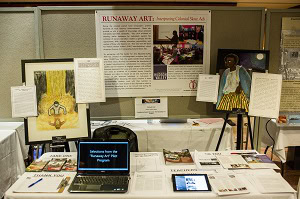

Michael Lord’s poster “Runaway Art” at the 2015 annual meeting in New York City. Credit: Mark Monaghan.

As I visited the exhibit, talked with presenters, and collected copies of their handouts, I realized that historical posters can serve quite a range of purposes. In some cases, the directness of visual communication suits the subject matter. Ann E. Robinson, a historian of science at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, revealed the complicated historical nature of the Periodic Table of Elements through its changing formats—even its creator, Mendeleyev, varied its presentation. Tyson Reeder, of the University of California, Davis, displayed the rebuilding of Lisbon after the 1755 earthquake, showing how the new city differed in its greatly expanded public sphere of straight streets and squares.

More often, historians at poster sessions seek to convey the nuances of their analysis. Ideally, historical poster scholarship defines a methodology and presents a historical argument, while providing background for each, then ties the package together with a lively title and an attractive image. Yet too many messages leave a blur: some poster makers fall prey to the temptation to add more text in steadily smaller fonts. The trick is making effective use of images and layout, ensuring that the text clarifies and amplifies the images.

Many posters at the 2015 exhibit met the challenge of illustrating a methodology and the historical results of its application. Vilja Hulden, a labor historian at the University of Colorado, Boulder, argued that employers developed the term closed shop (a union-only workplace); she backed up her analysis with Bayesian statistical procedures, which she explained in her poster. Andrea Felber Seligman (Allegheny Coll.) also offered methodology and interpretation, using historical linguistics to document inland trade in precolonial East Africa. In each case the results were rewarding, but they required the viewer to study rather than just glance at the poster. Emily Klancher Merchant, of the University of Michigan, had to use a text-only approach to explain her research, using network analysis to search texts and reconstruct the development of the discipline of demography.

Other posters hinted memorably at historical issues, leaving the viewer intrigued but needing to look further for a historical argument. One effective title was “Missing Links,” for a poster by Kathrinne Duffy (Brown Univ.) that showed that popular US exhibits of primates (such as a chimpanzee in Central Park) partook of the same social Darwinist logic framing the Jim Crow era and Chinese exclusion. Another striking title, “Runaway Art,” as presented by Michael Lord of Historic Hudson Valley, effectively hinted that runaway slaves of the antebellum United States produced representations of their experience, but one needed to visit the museum to learn the details.

Undoubtedly, the poster sessions at the 2016 AHA annual meeting in Atlanta will present an opportunity for both presenters and audience members: their interaction should help sharpen the contributions of these concise, visual discussions of historical problems. Visit the poster sessions at the Galleria Exhibit Hall in the Hilton Atlanta on Saturday (check the program for specific hours). And be sure to submit your poster proposal for the 2017 annual meeting in Denver by February 15.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.