Editor’s Note: This piece is first in a series of two posts on collaborative historical research. The second post can be found at here.

We are three historians who’ve collaborated in a variety of ways on several historical projects over the course of seven years. In the process, our intellectual work has taken turns we never envisioned. We hope that our discussions and approaches can push us all as historians to think about what collaboration looks like in our field, the expansive kind of work it can produce, and how we might infuse worth into undervalued aspects of collaboration.

Interviews in Lubumbasi allowed the researchers to gather both oral traditions and language data. Catherine Cymone Fourshey, second from left, Christine Saidi, third from left, and Rhonda M. Gonzales, far right.

Initially, our collaborative efforts were typical: coordinating conference panels or asking each other for feedback on individual research projects. A conversation over a meal at a conference about colonial-era anthropology and its often ahistorical treatment of “tribe” and “tradition,” however, led our scholarly work in a direction that was wholly unexpected. We first collaborated on writing an article on the subject. Now, our relationship has expanded into collaborating on a book project that attempts a longue durée history of a region stretching from the eastern Atlantic (modern day Democratic Republic of Congo) across central Africa (Zambia) to the western Indian Ocean (modern day Tanzania and Mozambique). In order to do justice to the layers and complexity of this macro-historical project, we have been collectively and simultaneously examining micro-level histories that, combined together, provide a larger tableau of historical shifts over time and space. Furthermore, the breadth and depth of this project benefits from our ability to collaboratively integrate the local, regional, and transregional.

Our impetus for sharing our experiences with collaboration comes from a panel at the 2017 AHA annual meeting titled “Is Collaboration Worth It?” which later became the basis of a Perspectives viewpoints article, “Whose Work Is It Really?” In the piece, Seth Denbo, AHA’s director of scholarly communication, points to the reductive way in which historical authorship is credited to only one individual despite multiple actors shaping the process of the final product. Denbo describes the multiple ways scholars interact and exchange ideas to produce new knowledge: gathering feedback through conversations, conceptualizing and vetting ideas at conferences and seminar tables, meeting during breaks in the halls and courtyards of archives, reading and citing each other’s work, and going through the peer review process, among others. Like Denbo, the panelists at the annual meeting session, and the large audience that attended the discussion, we see evidence that collaboration can expand the richness of research, thinking, and writing. (This is precisely why we agreed to co-author this blog post even though it is not going to count in our promotion or annual review enumerations.)

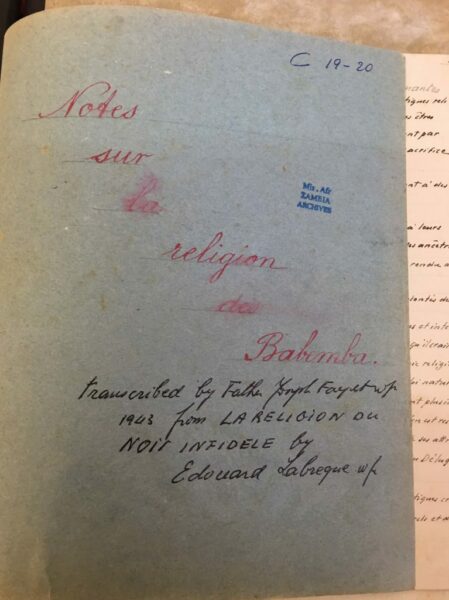

Notes on Bemba religion by Edward Labreque, one of the White Fathers missionaries and ethnographers of the late 19th- and early 20th-centuries. The notes provide both qualitative and quantitative data for previous centuries on generation, gender, family, and economy. Credit: Catherine Cymone Fourshey

One of the challenges of embarking on a collaborative history book project has been determining how we would collectively delve into the archives and conduct field interviews. As of now, the three of us have researched and written together an article, a book chapter, and a three-year NEH grant (“Expressions and Transformations of Gender, Family, and Status in Eastern and Central Africa 500–1800 CE,” RZ-249953-16) supporting our current research. During our first year, we intend to go through a large archive of over 10,000 documents collected by the White Fathers in Zambia and to conduct interviews in both Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo. We expect that this collaboration will allow us to tackle a large corpus of data and think through it from three perspectives, adding new dimensions to our analysis.

Of course, this sort of collaboration comes with the challenge of coordinating our travels to Central Africa. At the time of writing this reflection, we were still making last-minute preparations for our transnational research: contacting overseas colleagues, archivists, museum directors, and other local connections; booking flights and guest houses; applying for visas; purchasing supplies; securing research permits; and finalizing finances, all while maintaining our everyday family lives, personal health, and academic work. At times mundane, tedious, time-absorbing, and, occasionally, frustrating, these are some of the more practical aspects of collaboration.

Yet, there are myriad reasons, both professional and personal, that leads us to collaborate and that might make it compelling for others considering doing the same. These include holding one another accountable, supporting and encouraging each other, building a sustained intellectual community, and receiving timely peer feedback and critique. We find that working together has energized our collective and individual work. At each stage, we have added our individual historical vision to the endeavor while engaging the ideas of others. We believe that our joint venture has resulted in more expansive and nuanced analyses in our individual and collective final products.

Nevertheless, there are significant apprehensions about historical collaborations. Our aim in this post has been to point to some of its virtues. While working against the preference for single-authored works is challenging, it also creates new possibilities to exceed any result(s) one scholar could achieve individually.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Christine Saidi is a professor of African and world history at Kutztown University. She has conducted research in Somalia, Rome, Zambia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Saidi has authored many scholarly articles, a book, co-authored a book, and is currently writing a textbook on the history of African women.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.